1 - Welcome to #ThreadTalk, #LaborDay edition. Our topic? Mills, Strikes & Textile Labor.

Buckle up, though. There is a distinct lack of dazzle today.

We're meeting the makers & laborers of apparel history--& how they lived & died for their craft.

Buckle up, though. There is a distinct lack of dazzle today.

We're meeting the makers & laborers of apparel history--& how they lived & died for their craft.

2 - In Asia, & China specifically, silk became one of the first real fabric blockbusters for trade during the Han Dynasty, beginning the Silk Road.

Traditionally, weaving was left to women while men farmed & sold, and this continued as trade grew.

Traditionally, weaving was left to women while men farmed & sold, and this continued as trade grew.

3 - Francesca Bray puts it simply in "Textile Production & Gender Roles":“The growth of the textile industry involved new forms of organization of production that made men the skilled workers and marginalized women.”

This is by no means unique to China. It's the story of fabric.

This is by no means unique to China. It's the story of fabric.

4 - Silk farming was done on large & small scale, also often overseen by women. But profits, as we'll continue to see, were controlled predominately by men. China was not the first of the last country to politicize fabric.

Pictured, sorting cocoons in the Song Dynasty.

Pictured, sorting cocoons in the Song Dynasty.

5 - Fabric-making & its related trades requires keen eyes, focus, & lots of repetitive work. But as demand/technology grows, the rights of those doing the work diminish.

In the Middle Ages, the rise of guilds started to address protections. Sort of. If you're a man.

In the Middle Ages, the rise of guilds started to address protections. Sort of. If you're a man.

6 - With few exceptions, could not join guilds. Or if they could (especially if widowed) working hours/rules made it difficult to reap any benefits.

Depending on location, etc., (and of course talent, because talent = money) there were those who managed. 14c women sewing, below

Depending on location, etc., (and of course talent, because talent = money) there were those who managed. 14c women sewing, below

7 - The first protest I could find in Medieval Europe was 1274, in Ghent, when guild workers (weavers & fullers) united against working conditions.

Their employers reached out to all the nearby towns, & the strikers were locked out of work. Another occurred in 1303.

Their employers reached out to all the nearby towns, & the strikers were locked out of work. Another occurred in 1303.

8 - The weavers & fullers had quite a bit of influence for decades to come. By the mid-15th century, there was an all-out revolt in prosperous Ghent, against Phillip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. A few years, and 20,000 deaths later, Ghent fell...

9 - Now, enter the Luddites. Their leader was supposedly a man named Ned Ludd, but there's no proof he actually existed. Their focus? Destroying machinery that was taking their jobs. It started in Nottingham (yes, that one) and quickly spread, a rebellion lasting from 1812-16.

10 - But wait, maybe it's not that easy. Historians argue that it wasn't just about jobs & technology. It was about being heard. The Luddites might not have cared about the tech at all--they just needed to hit 'em where they hurt.

We still use the term today, perhaps erroneous.

We still use the term today, perhaps erroneous.

11 - Parliament had to act fast because it was working. The Luddites were well-coordinated & secretive. And they made big news: Lord Byron was a vocal supporter after the law came down super hard on them (including executions and penal transportation). Below, Byron's smolder.

12 - Of course, this is all super ironic, because at this time, we're at the peak muslin imports from the Dhaka region. And talk about horrific working conditions and no wages...

There's a whole other #threadtalk on that subject, if you missed that...

There's a whole other #threadtalk on that subject, if you missed that...

https://twitter.com/NataniaBarron/status/1374134942385442816

13 - More on that in a minute...

Seamstresses started working together for better wages & working conditions, collaborating with none other than Susan B. Anthony, in the 1860s. Unlike dressmakers, seamstresses were paid by the piece & worked incredibly long hours (16h or more).

Seamstresses started working together for better wages & working conditions, collaborating with none other than Susan B. Anthony, in the 1860s. Unlike dressmakers, seamstresses were paid by the piece & worked incredibly long hours (16h or more).

14 - "The manner in which these women lived, the squalidness and unhealthy location and nature of their habitations... can be easily imagined; but we assure the public that it would require an extremely active imagination to conceive the reality.” NY Daily Tribune, March 7, 1845

15 - If this sounds familiar, this was what gave rise to sweatshops. Yes, factories were awful. But the contract model meant that immigrants, their families, children, and neighbors, could all "get in" on the work.

Great overview: americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops/his…

Great overview: americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops/his…

16 - Sentiment started to change after 1900. In 1911, came the Triangle Shirtwaist fire where 146 garment workers--mostly women & girls--died. The youngest were 14. When the building caught fire, they could not escape because the doors had been sealed against theft & truancy.

17 - The horror of hearing & seeing women falling to their deaths raised public awareness. Even though workers had been dying from brown lung, arsenic poisoning from green dye & a variety of other ailments for ages, they couldn't ignore this one. NYC stood still. Funeral, below.

18 - Then in 1912 came the Bread & Roses strike in Lawrence, MA. Downplayed at the time as a "spontaneous" event, modern historians now believe it was a significant, coordinated strike. And it was inclusive of people across racial, ethnic, and gender lines.

19 - 1/3 of workers in Lawrence, a local physician reported, died before the age of 25. And the mill employed children under 14 (illegal at the time). Mill capacity: 32,000 workers, who earned about $9.00 for 60 hours/week.

20 - Things got heated. The police did as you'd probably expect. The militia got called in. But the strikers did not back down. First Lady Helen Taft got wind, the Senate got involved, and eventually the strikers got higher wages... well, for a while, anyway.

21 - It was the first of many strikes, but eventually the textile industry retreated from New England altogether. Went somewhere, right?

So, about India. Prior to the 1920s, we have very little written record of uprisings or strikes. Because imperialism. But there were strikes.

So, about India. Prior to the 1920s, we have very little written record of uprisings or strikes. Because imperialism. But there were strikes.

22 - Mills in India were about five times the size of an average mill (in the 1920s) as in the US or England. And we know that in spite of imperial rule, serious attempts were made at mobilization and better conditions by the “Bombay Mill Hands Association” as early as 1884.

23 - N.M. Lokhande, previous picture, helped establish basic rights for workers including:

- a weekly Sunday holiday

- In the afternoon, 1/2 hour break

- work from 6:30am and close by sunset

- salaries paid on the 15th of each month

- a weekly Sunday holiday

- In the afternoon, 1/2 hour break

- work from 6:30am and close by sunset

- salaries paid on the 15th of each month

24 - And now, well, fashion is even faster. The machinery still needs little hands. Sweatshops are still everywhere. Industrialization has shifted the American and British textile industries, but it's still not changed. @UNICEF has a sobering look.

labs.theguardian.com/unicef-child-l…

labs.theguardian.com/unicef-child-l…

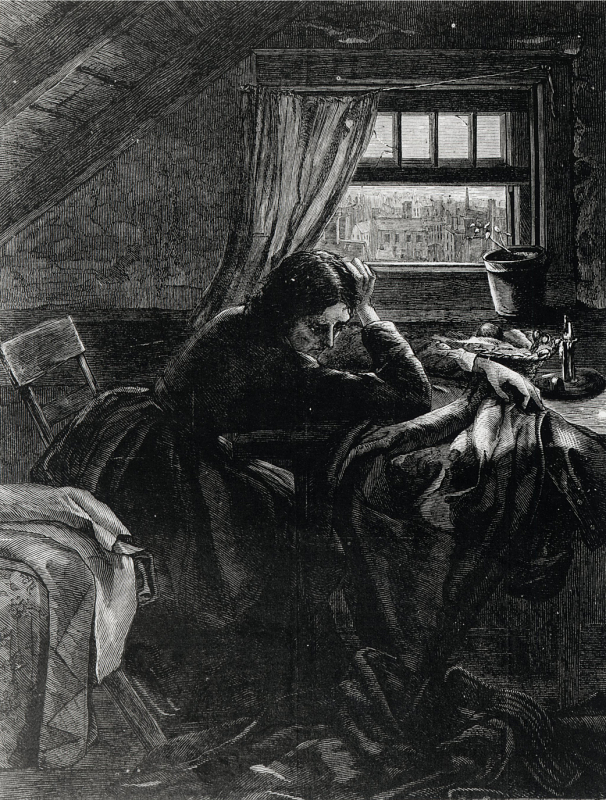

25 - That family on the first image? You know what they're doing? They're making ornamental flowers for hats. Green flowers made with dye laced with arsenic. Scheele's green. A green we knew was poison for years, but let workers get sick because it was an illness of the poor.

26 - Lacemakers and seamstresses and dyers went blind. Factory workers died horrific deaths. Fashion is beautiful--it's art. But it's also built on privilege, on power, and meant for those who want more of it. This thread was just the tip of the iceberg, really. So much more...

27 - Twitter isn't the best medium for this deep dive stuff--it's hard to really convey. But it's worth considering today especially.

The history of sweatshops in the US by the @smithsonian is really remarkable stuff. Read it if you have the time.

americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops

The history of sweatshops in the US by the @smithsonian is really remarkable stuff. Read it if you have the time.

americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops

28 - Lots of sources. Part I

China

jstor.org/stable/4329048…

fromental.co.uk/craftsmanship/…

sino-platonic.org/complete/spp24…

India

jstor.org/stable/25249168

jstor.org/stable/4370842

groundxero.in/2019/06/03/the…

indianfolk.com/story-bombay-m…

China

jstor.org/stable/4329048…

fromental.co.uk/craftsmanship/…

sino-platonic.org/complete/spp24…

India

jstor.org/stable/25249168

jstor.org/stable/4370842

groundxero.in/2019/06/03/the…

indianfolk.com/story-bombay-m…

29 - Part II

Ghent & Guilds , etc.

the-low-countries.com/article/weavin…

google.com/books/edition/…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revolt_of…

Luddites

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stocking_…

Lawrence

ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/19…

jstor.org/stable/20148025

zinnedproject.org/materials/brea…

Ghent & Guilds , etc.

the-low-countries.com/article/weavin…

google.com/books/edition/…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revolt_of…

Luddites

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stocking_…

Lawrence

ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/19…

jstor.org/stable/20148025

zinnedproject.org/materials/brea…

30 - Part III

General History

ncpedia.org/anchor/work-te…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_…

bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guide…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_o…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_…

americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops/his…

labs.theguardian.com/unicef-child-l…

theparisreview.org/blog/2018/05/0…

General History

ncpedia.org/anchor/work-te…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_…

bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guide…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_o…

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_…

americanhistory.si.edu/sweatshops/his…

labs.theguardian.com/unicef-child-l…

theparisreview.org/blog/2018/05/0…

31 - And that does it for this week's #threadtalk. A last reminder that this is not ancient history... this is still happening.

Signing off. Thanks for reading.

Signing off. Thanks for reading.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh