1. Now that a lot more people are paying attention to #SCOTUS's "shadow docket," here's a quick #thread on what, exactly, people *mean* when they use that term — and why, even before Wednesday's #SB8 ruling, it's been a source of increasing controversy over the past few years:

2. The term was coined by @WilliamBaude in 2015 as a catch-all for just about everything #SCOTUS does *other* than decide the big "merits" cases it hears each Term — in which it receives multiple rounds of briefing; holds oral argument; and hands down lengthy, signed opinions.

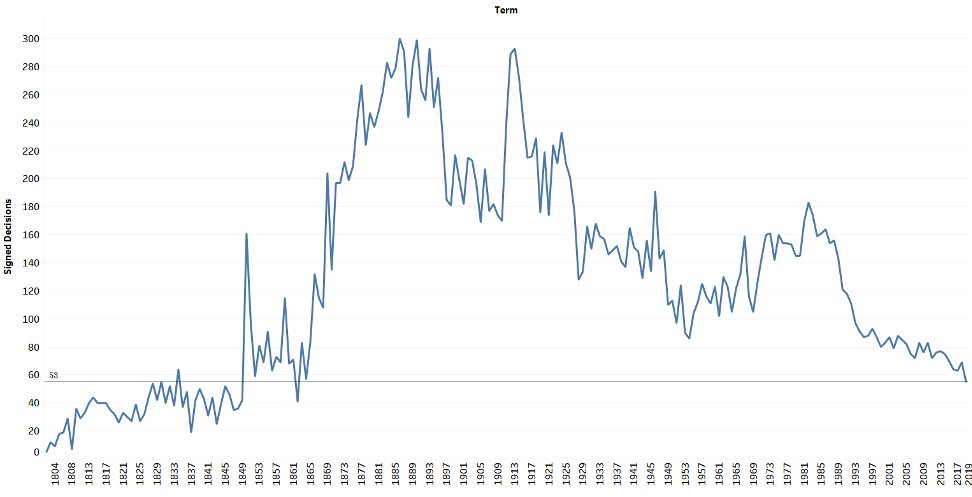

3. The "merits" docket includes only ~70 cases per Term. As @AdamSFeldman has shown, there's been a sharp decline in these cases in recent years. During its October 2019 Term, the Court handed down 53 decisions in such cases (the fewest since 1862); this Term, there were only 56.

4. Thus, *most* of the Court's work is on the "shadow docket," where it issues "orders," virtually all of which are unsigned and unexplained. Some of these orders are banal (giving parties more time for briefs); others control the merits docket (e.g., by granting/denying review).

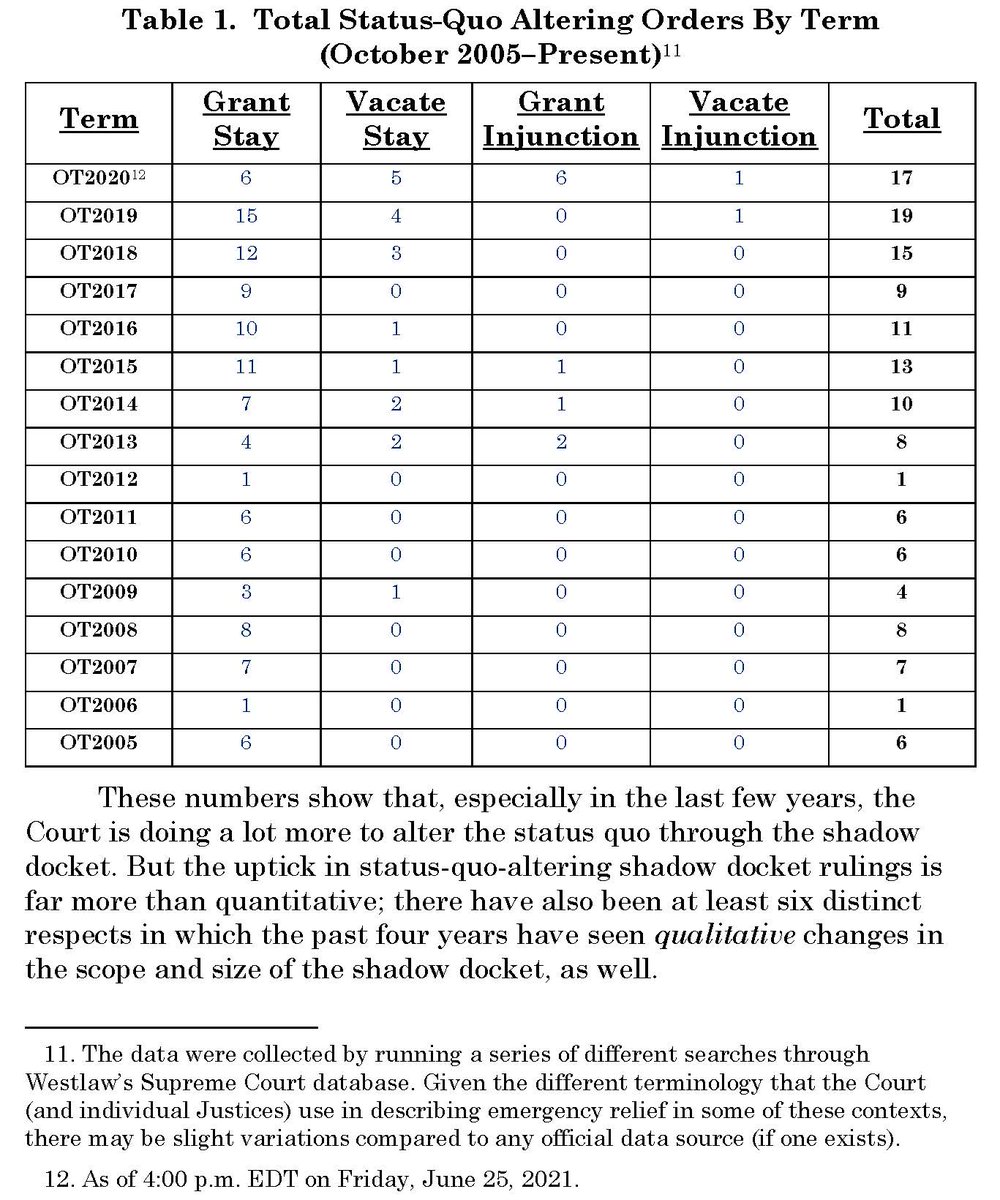

5. The *real* uptick in recent years has come in what, historically, has been a tiny subset of the Court's orders—granting or denying a party's request for "emergency" relief, i.e., an order from #SCOTUS that, at least in theory, temporarily changes the status quo pending appeal.

6. There are lots of examples, but the most common are:

a. stays of lower-court rulings to freeze their effect (e.g., staying a lower-court injunction);

b. lifting lower-court stays (so, letting government policies go into effect); or

c. injunctions directly blocking policies.

a. stays of lower-court rulings to freeze their effect (e.g., staying a lower-court injunction);

b. lifting lower-court stays (so, letting government policies go into effect); or

c. injunctions directly blocking policies.

7. It's here where we've seen such a massive uptick in recent years. So far this Term, there have been *19* such rulings; there were 19 last Term; and 15 the Term before that. In contrast, from OT2005-OT2014 (Chief Justice Roberts's first 10 years), the average was 5.7 per term.

8. It's not just a numerical uptick; most such rulings before 2015 involved last-minute execution disputes—where the rulings affected only the state and the prisoner. Since 2015, we're seeing far more rulings directly affecting whether state/federal policies are in effect or not.

9. So these emergency rulings that are only supposed to be temporary are having massive effects far beyond the individual parties to the case — e.g., the August 26 order vacating a lower-court stay and thereby blocking (effectively permanently) the CDC's eviction moratorium.

10. Just as important (but harder to track) are cases in which #SCOTUS *refuses* to grant emergency relief. Wednesday's ruling in the #SB8 case is a good example: The providers had sought either an injunction against the law or a vacatur of a lower-court stay, but got neither.

11. When the Court issues an order in this context, it's usually unsigned and unexplained, leaving us to wonder exactly why it did (or did not) grant relief; and whether (and to what extent) the ruling should have precedential effect in other contexts. Here's the 8/24 MPP ruling:

12. Even when the Court provides *some* reasoning, as a 5-4 majority did in Wednesday's #SB8 ruling, the analysis is usually cryptic and open-ended — raising as many questions about the underlying legal issues as it answers, and so leaving the law unsettled as litigation unfolds:

13. Along the way, and unsurprisingly, these rulings are also becoming *far* more divisive, with far more public dissents — *all* of which are breaking down along strict ideological lines:

Data on volume:

Data on ideology:

Data on volume:

https://twitter.com/steve_vladeck/status/1434568812045742086?s=20; and

Data on ideology:

https://twitter.com/steve_vladeck/status/1434002701881380864?s=20

14. There's a lot to say about why this is all happening (including why more of these applications are coming to the Court and why the Justices are granting more of them).

I've said much of it in my June 30 testimony to the #SCOTUS reform commission:

whitehouse.gov/wp-content/upl…

I've said much of it in my June 30 testimony to the #SCOTUS reform commission:

whitehouse.gov/wp-content/upl…

15. But the purpose of this thread is not to relitigate those debates. Again, my testimony is a good place to start for more on that. Rather, my goal here is just to describe what we *mean* when we use the term — and to explain why it's only recently become such a big deal.

/end

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh