Today, the EEF released a systematic review which challenges the way we think about effective Professional Development (PD).

A thread on my interpretation of what they found and why it's important.

↓

A thread on my interpretation of what they found and why it's important.

↓

First, a bit of background...

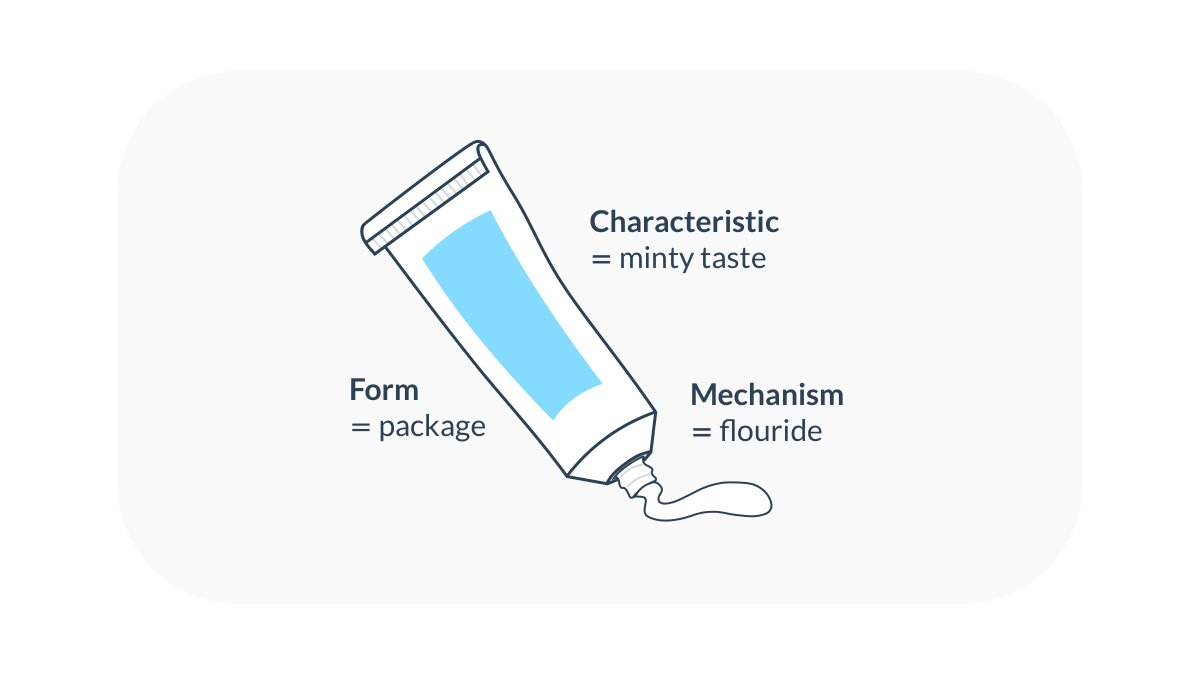

Until recently, PD effectiveness has mostly been thought about in terms of either 'forms' or 'characteristics'.

→ Forms are things like: instructional coaching or lesson study

→ Characteristics are things like: collaborative or sustained

Until recently, PD effectiveness has mostly been thought about in terms of either 'forms' or 'characteristics'.

→ Forms are things like: instructional coaching or lesson study

→ Characteristics are things like: collaborative or sustained

However, a recent analysis by @DrSamSims & @HFletcherWood (2019) proposed a third way.

In addition to thinking about forms and characteristics, they hypothesised that thinking about PD in terms of 'mechanisms' might add even more power and nuance to our perspective.

In addition to thinking about forms and characteristics, they hypothesised that thinking about PD in terms of 'mechanisms' might add even more power and nuance to our perspective.

Mechanisms are processes that directly change knowledge, skills or behaviour—approaches typically grounded in evidence from cognitive and behavioural sciences.

→ Things like: goal setting or feedback

→ Things like: goal setting or feedback

Crucially, mechanisms isolate the *causes* of effective PD better than characteristics or forms. Consider a toothpaste analogy:

→ If the form is the package of ingredients

→ Then a characteristic might be the minty taste

→ And a mechanism would be the fluoride

→ If the form is the package of ingredients

→ Then a characteristic might be the minty taste

→ And a mechanism would be the fluoride

Additionally, because mechanisms are... well, mechanisms... they also communicate *how* the change works.

They provide an 'under the hood' understanding of how certain causes generate change. And in doing so: they help PD designers build 'adaptive expertise'.

They provide an 'under the hood' understanding of how certain causes generate change. And in doing so: they help PD designers build 'adaptive expertise'.

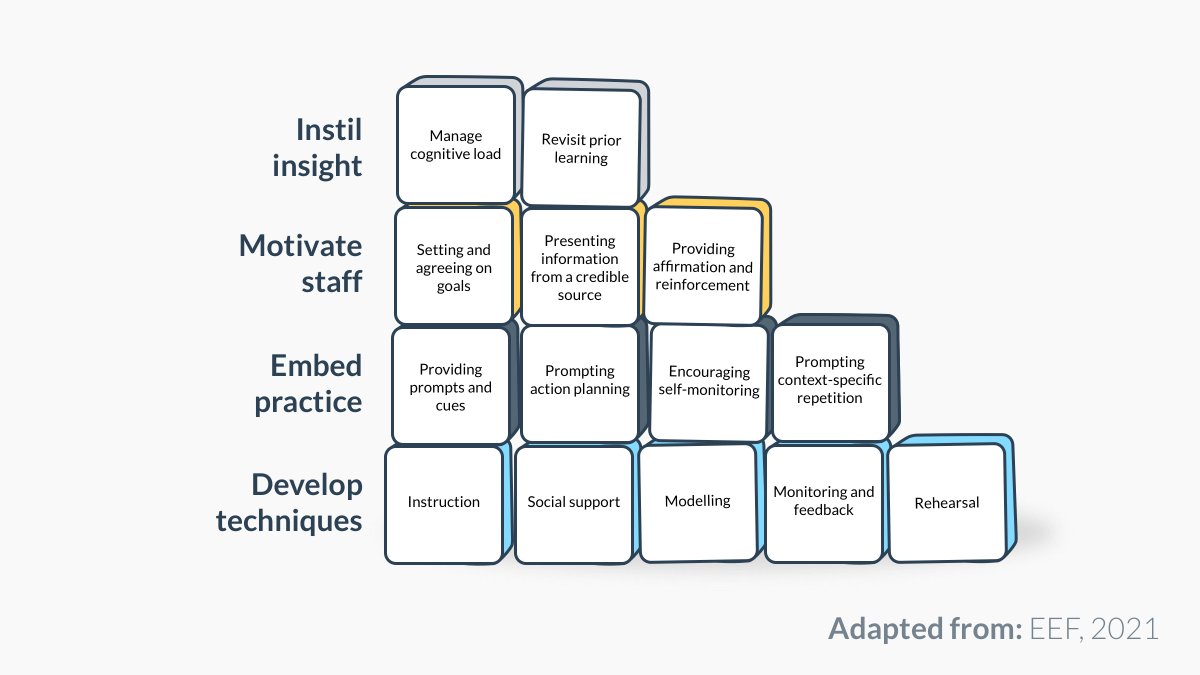

The authors suggest that mechanisms are best thought of as the essential 'building blocks' of effective PD.

The more that are present, the more effective the PD will be. And vice versa.

No fluoride = unhealthy teeth.

The more that are present, the more effective the PD will be. And vice versa.

No fluoride = unhealthy teeth.

They identified 14 mechanisms, grouped into 4 PD purposes, and found that:

👇 PD with no mechanisms had zero effects

☝️PD with lots of the mechanisms had effect sizes of around 0.17, equivalent to around +2 months of additional pupil progress

👇 PD with no mechanisms had zero effects

☝️PD with lots of the mechanisms had effect sizes of around 0.17, equivalent to around +2 months of additional pupil progress

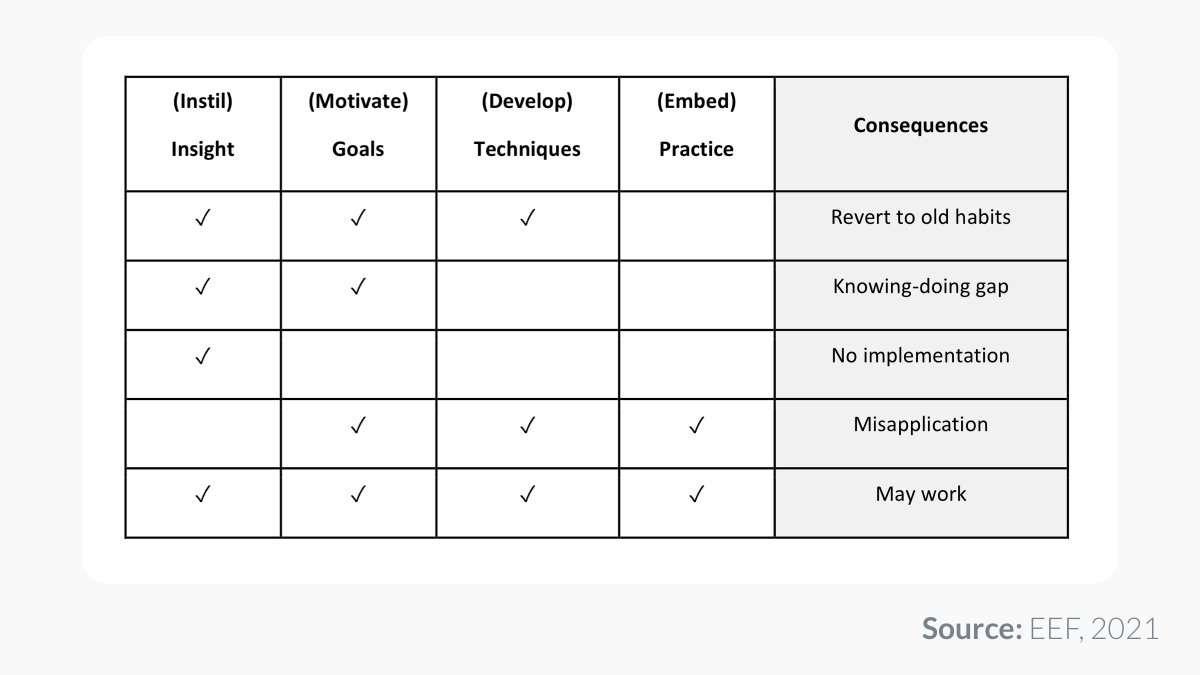

Furthermore, they found indications that the more 'balanced' the PD was—as in, it had at least one mechanism from each group—the more effective it was.

And they conjectured how PD might fail, should it omit any of these critical groups.

And they conjectured how PD might fail, should it omit any of these critical groups.

So, what does this all this mean in practice?

Personally, I think it pushes us to think differently about how we evaluate, talk about, and design for PD.

Personally, I think it pushes us to think differently about how we evaluate, talk about, and design for PD.

For example, it doesn't really make sense to talk about whether instructional coaching or lesson study are 'effective' or 'ineffective' (or even a 'fad').

Because forms like this can vary quite a lot, and so it *depends* which mechanisms they contain and how they are organised.

Because forms like this can vary quite a lot, and so it *depends* which mechanisms they contain and how they are organised.

It's probably more fruitful to ask ourselves:

→ What mechanisms does this PD form contain?

→ How are they organised, and how is the whole thing implemented?

And then spend our time discussing this stuff.

→ What mechanisms does this PD form contain?

→ How are they organised, and how is the whole thing implemented?

And then spend our time discussing this stuff.

Relatedly, for those designing PD, there's value in taking a 'mechanisms-first' approach.

This entails thinking less about forms (instructional coaching or lesson study) and more about whether effective mechanisms—the essential building blocks—are in place.

This entails thinking less about forms (instructional coaching or lesson study) and more about whether effective mechanisms—the essential building blocks—are in place.

For example, PD designers might ask themselves:

→ What suite of mechanisms do we want to incorporate?

→ How best might we combine, package and implement them?

→ What suite of mechanisms do we want to incorporate?

→ How best might we combine, package and implement them?

Important question: what are the likely lethal mutations? Hard to say, but one guess:

🦠Adopting a tick box approach, rather than taking the time to develop a deep understanding of mechanisms, which are often fairly complex and nuanced psychological and behavioural phenomena.

🦠Adopting a tick box approach, rather than taking the time to develop a deep understanding of mechanisms, which are often fairly complex and nuanced psychological and behavioural phenomena.

A good place to *start* developing that understanding is Appendix 5 of the full report. For each mechanism, it provides:

→ An overview of the evidence base

→ A short summary the how the mechanism works

→ An example and non-example

→ An overview of the evidence base

→ A short summary the how the mechanism works

→ An example and non-example

Finally, a quick thought on 'where next?'

This study moves many things forward, but for me, the next frontier is around the interplay between PD 'content' and PD 'process'.

Tbf the study *does* dig into this a bit, but I think there's more depth to be mined.

This study moves many things forward, but for me, the next frontier is around the interplay between PD 'content' and PD 'process'.

Tbf the study *does* dig into this a bit, but I think there's more depth to be mined.

For example, how might the mechanisms be different if we're trying to help teachers develop better assessment approaches vs better behaviour management.

Also: mechanisms-rich PD on brain gym is never going to have +ve impact.

Also: mechanisms-rich PD on brain gym is never going to have +ve impact.

In summary:

→ This is a significant contribution to the knowledge base around PD

→ It challenges how we think, talk about, and design PD

→ And hopefully paves the way for even more research in this area🤞

→ This is a significant contribution to the knowledge base around PD

→ It challenges how we think, talk about, and design PD

→ And hopefully paves the way for even more research in this area🤞

*HUGE* snaps to:

→ The team: Sam, Harry, Alison, Sarah, Claire, Jo & Jake

→ All those PD researchers who's shoulders this study stands on

→ And @EducEndowFoundn for having the foresight to invest in this

→ The team: Sam, Harry, Alison, Sarah, Claire, Jo & Jake

→ All those PD researchers who's shoulders this study stands on

→ And @EducEndowFoundn for having the foresight to invest in this

Reminder: this is just *my interpretation*. Prob best to read the reports and come to your own conclusions:

→ Guidance report d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/guidance-repor…

→ Full report d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/documents/page…

👊

→ Guidance report d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/guidance-repor…

→ Full report d2tic4wvo1iusb.cloudfront.net/documents/page…

👊

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh