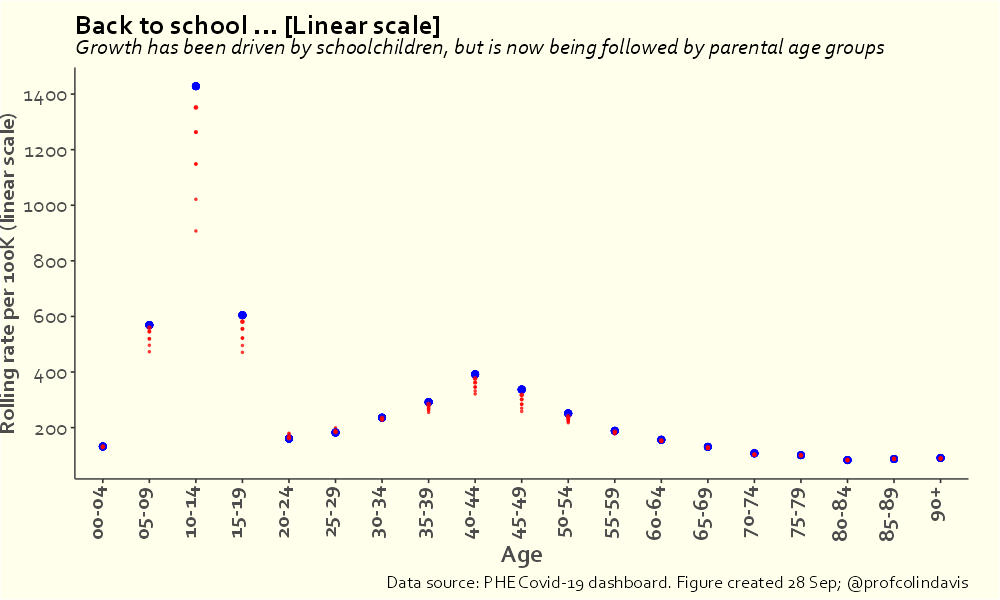

An argument I've been trying to make for a long time is that mass infection of children is not only bad for children, but also bad for adults, because rates in children affect rates in adults (because that's how infectious diseases work). Here's another way of looking at that.🧵

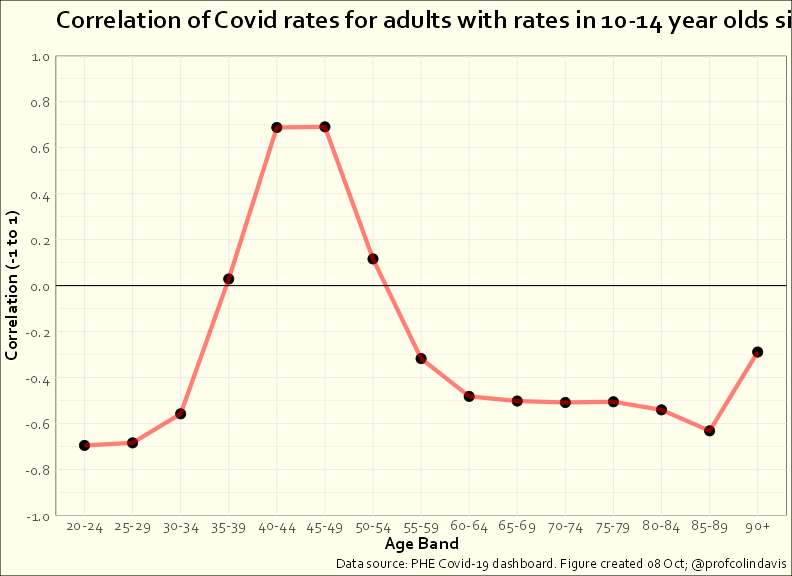

This plot answers the following questions:

a) if I know Covid rates in school-age children (5-9s & 10-14s), how accurately can I predict rates in adults?

b) which adult age bands will I be able to predict most accurately?

[SPOILER: There aren't going to be any surprises here]

a) if I know Covid rates in school-age children (5-9s & 10-14s), how accurately can I predict rates in adults?

b) which adult age bands will I be able to predict most accurately?

[SPOILER: There aren't going to be any surprises here]

The data set covers the entire pandemic to date in England (30 Jan 20 - 3 Oct 21). The y-axis measures how well we can predict rates for a given adult age group on a given day if we know the rates for 5-14 year olds from 2 days earlier. (A value of 1 would be perfect prediction).

The best predictions can be made for 40-44 year olds, but good predictions are possible throughout 30-49s. Accuracy of prediction falls off roughly symmetrically around the 40-44 peak, but then goes up again for 65-74 year olds, before dropping off rapidly for older age groups

Now sure, some proportion of the predictive power here relates to general "community transmission", but I don't think it's too much of a stretch to look at these peaks and suggest that they reflect parents and grandparents.

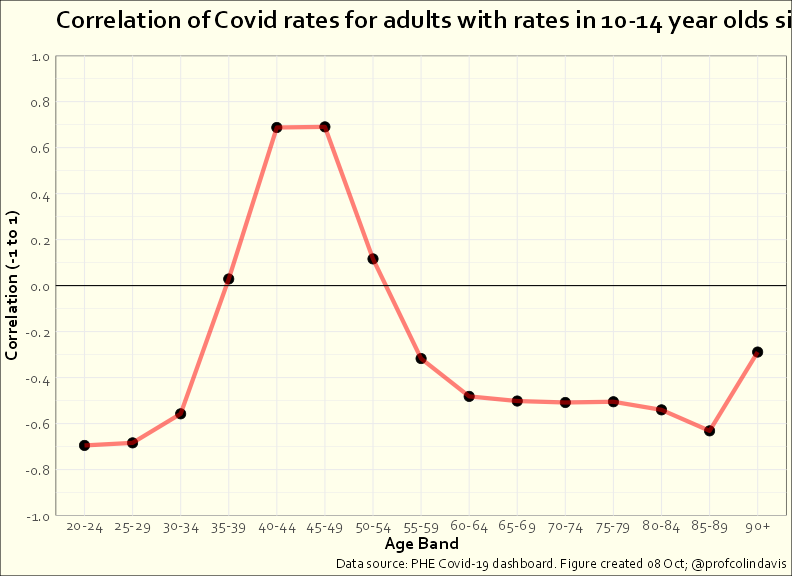

As I said, that plot covers the whole pandemic, so we might want to look at what's been happening more recently. Here's a plot of the correlations between rates in 10-14s and adult rates 5 days later since September.

Correlations can range from -1 to 1, where 0 would mean no relationship and 1 would mean a perfect correlation. The value of about .7 for 40-49s shows again how closely this age group follows 10-14s.

The negative correlations for most groups is because rates have been falling in these groups even as they've been rising in 10-14s and 40-49s. What we're seeing in 35-39s and 50-54s is probably the result of the mixture of parents ⬆️ and non-parents ⬇️in these age groups.

None of this necessarily implies causality, of course. But when you combine graphs like the above with graphs that plot rates changing over time, I think it gets harder to deny that increases in rates in children tend to lead to (smaller) increases in rates in parents.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh