The US beef industry is trying to deflect their responsibility for methane emissions by claiming that emissions US cows are no longer increasing atmospheric methane concentrations. This is technically true, and completely besides the point.

A quick thread: 1/15

A quick thread: 1/15

https://twitter.com/ben_elgin/status/1450482696077991940

The climate impacts of methane is usually compared with CO2 through the use of Global Warming Potentials (GWPs). There are usefully simple multipliers for a single year's emissions, but provide a misleading impression when applied to emissions over time. 2/

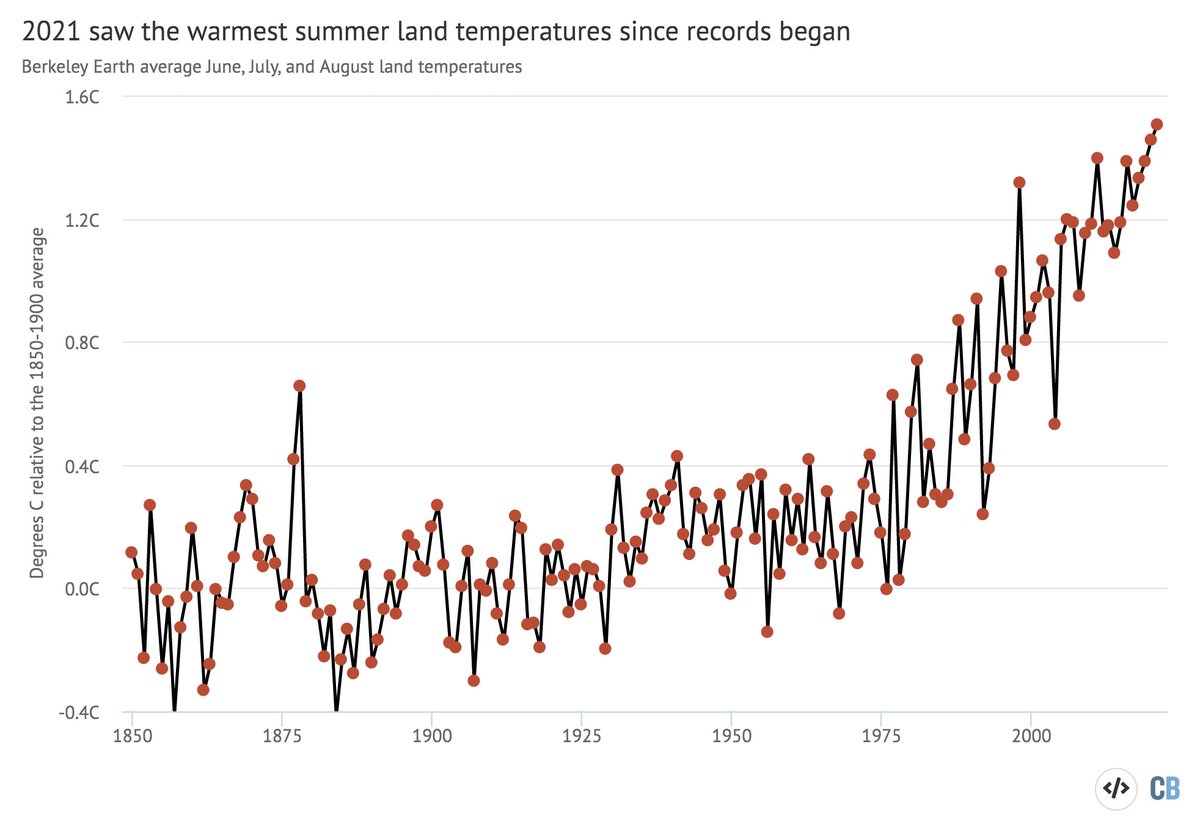

CO2 and methane (CH4) have very different lifetimes. When a ton of CO2 is emitted to the atmosphere, a portion is absorbed quickly, but around 40% remains after a century (and 20% after thousands of years). CH4 is removed much faster, with most gone after 20 years. 3/

CO2 is a very stable molecule while CH4 is not. CO2 can only be removed from the atmosphere by being absorbed by vegetation on the land or by the oceans. CH4, on the other hand, oxidizes in the atmosphere after interacting with hydroxyl radical (OH). 4/

What this means, in effect, is that CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere while CH4 does not. CO2 in the atmosphere is a result of all our emissions emissions since the industrial revolution, while the amount of CH4 depends on our rate of our emissions over the past decade or so. 5/

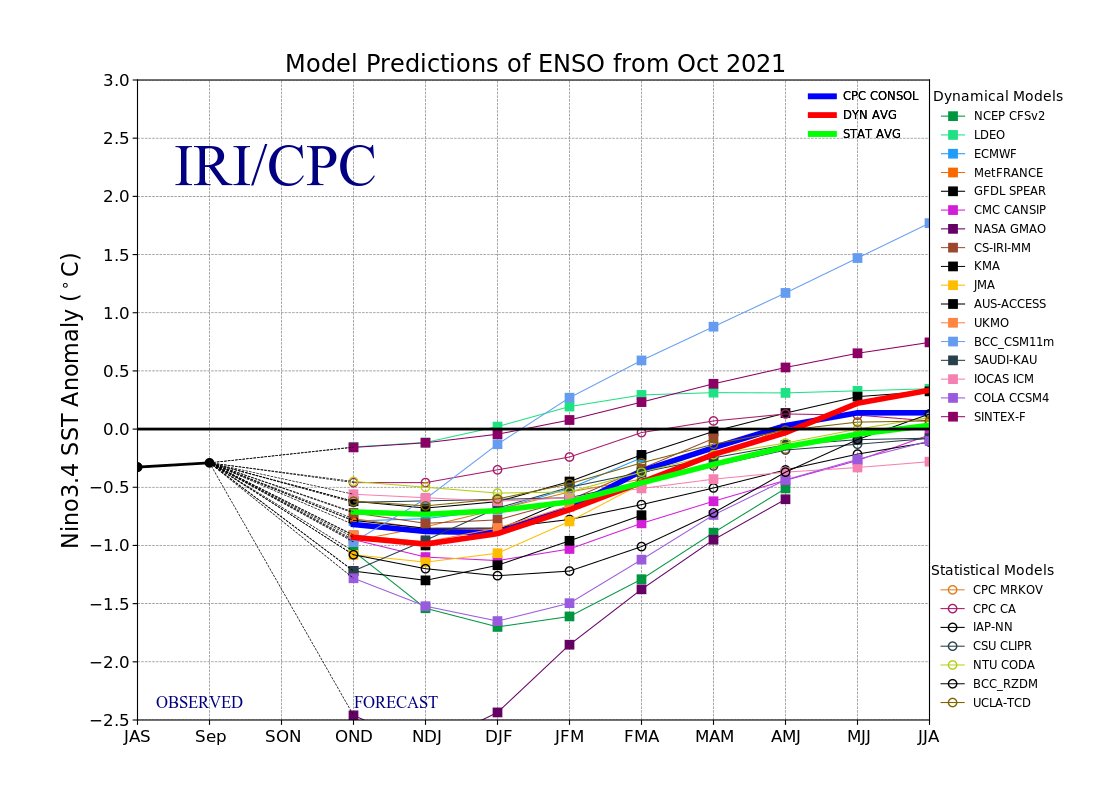

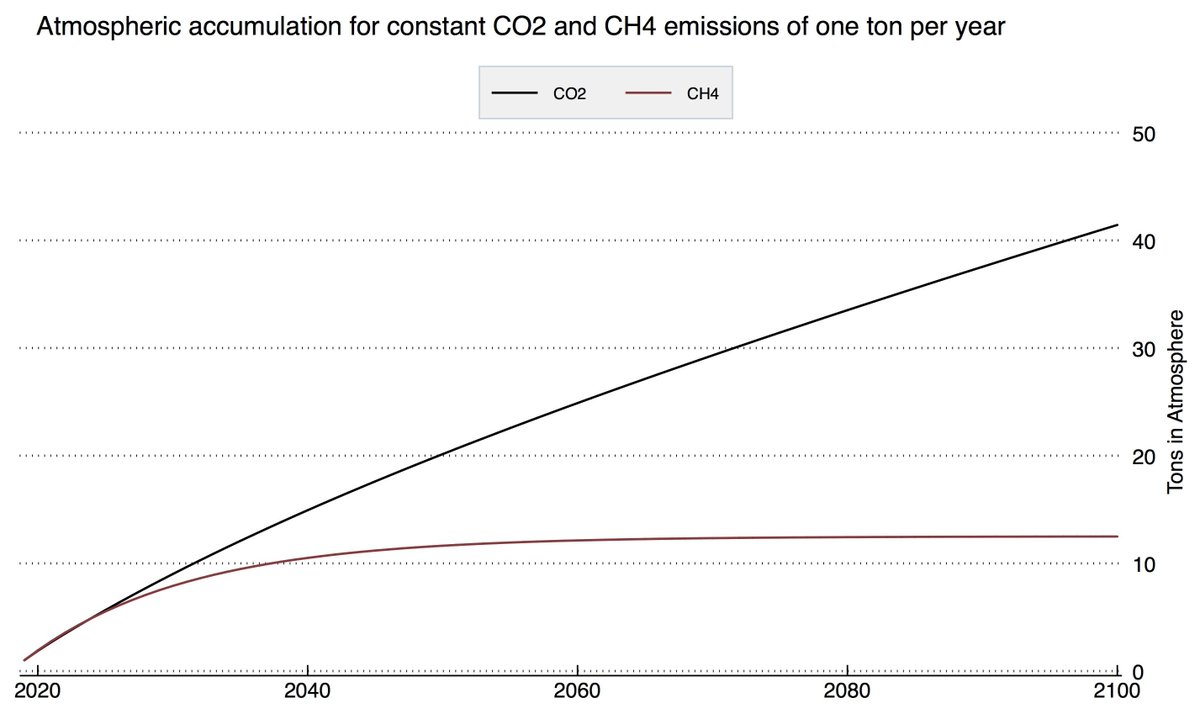

Here is what happens to atmospheric CO2 and CH4 if we emit 1 ton per year for the next 80 years: atmospheric CH4 stabilizes after 20 years or so, while atmospheric CO2 continues to grow: 6/

Traditional GWPs do not capture these dynamics at all. They end up overestimating the warming effect of CH4 emissions over time when emissions are increasing when using a 20-year time horizon, and underestimating it when using a 100-year time horizon. 7/

On the flip side, both GWP-20 and GWP-100 overestimate the warming effects of CH4 over time if methane emissions decline.

Thankfully theres a better metric – GWP* – that accurately translates CH4 emissions over time into warming the world experiences: carbonbrief.org/guest-post-a-n… 8/

Thankfully theres a better metric – GWP* – that accurately translates CH4 emissions over time into warming the world experiences: carbonbrief.org/guest-post-a-n… 8/

As the recent IPCC 6th Assessment Report shows, GWP* does a good job of translating CH4 emissions into warming both when emissions are increasing and (in the future) when they are hopefully decreasing (black line is actual warming, green line is GWP*): 9/

However, as the Bloomberg piece points out, some in the beef industry are using GWP* to claim that they are not contributing to climate change anymore, as their herds have not grown (and their CH4 emissions have not increased) over the past decade. 10/

While its technically true that other sectors are contributing to the -increase- in global CH4 emissions today, this misses the fundamental fact that the world needs to dramatically decrease its CH4 emissions to have any hope of meeting its ambitious climate goals. 11/

US cows have contributed a non-trivial chunk of current CH4 in the atmosphere, and are responsible for a portion of historical warming. That herd sizes and beef consumption is not increasing is good, but thats a bar so low its nearly meaningless. 12/

From this standpoint, decreasing US herd sizes (e.g. through people eating less beef and more beef alternatives) or other interventions to reduce US beef CH4 emissions has the exact same effect on the climate as avoiding increasing herd sizes in other countries. 13/

Given that US beef consumption is the 4th highest per capita its more than a little unjust to blame rising CH4 on increased consumption in poorer countries who consume a fraction of the beef a typical American does. 14/

So yes, GWP* is a better metric to use, and in a sense cow herds are like closed powerplants. But we need to dramatically reduce CH4 emissions, not just hold them flat, and US beef producers are still on the hook for their contribution to climate change.

https://twitter.com/hausfath/status/1230929548880969728

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh