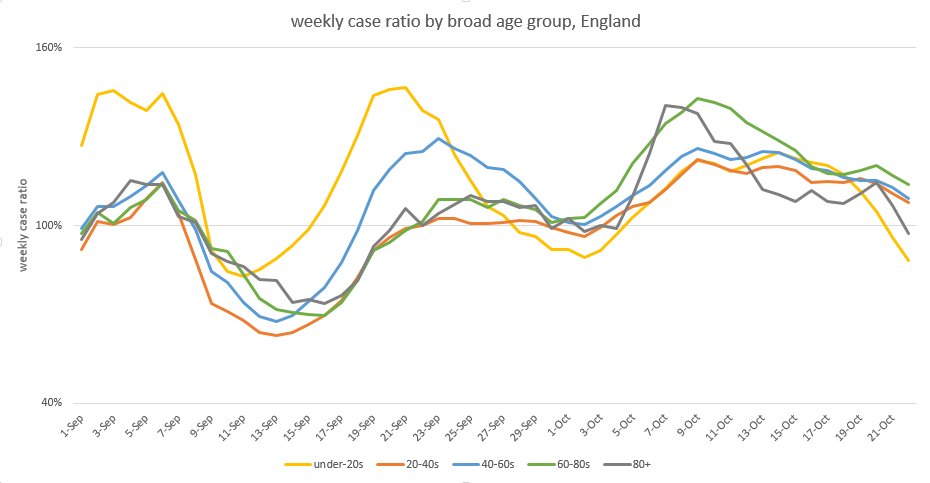

I usually like to mix good news and bad news (“this.. but also that”). But I can’t find any bad news in today’s dashboard data, so here goes with a happy half-term round-up. Case growth continuing to fall, and now even more steeply in the under-20s:

Looking back at the overview, the 80+ are in better shape as well. Note that last datapoint will get revised up, so may not really be below the axis, but it’s still heading in the right direction.

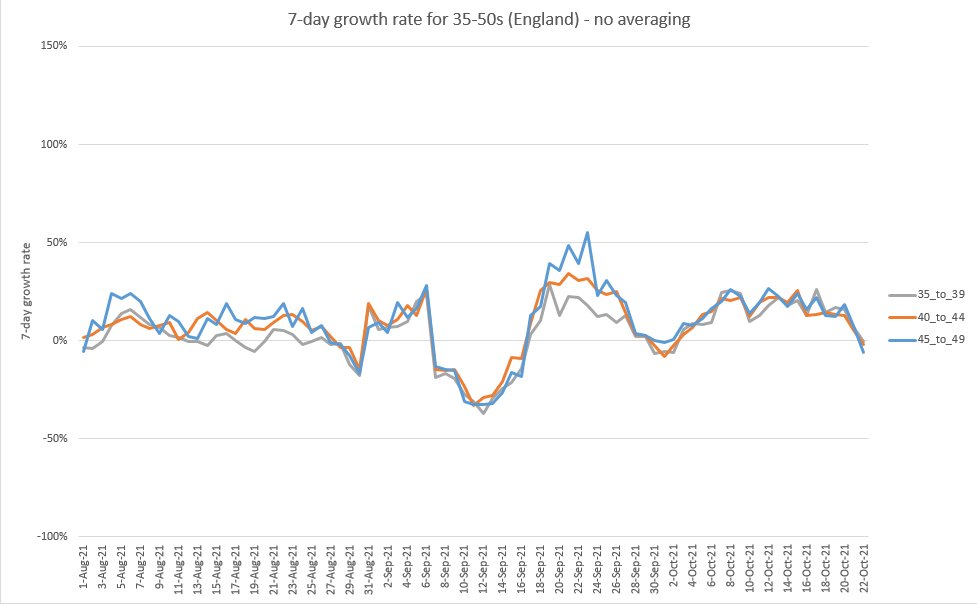

And the thing I like best in the case data isn’t very visible yet, but just a hint that cases in the 35-50 age groups are starting to stall as well – just a few days after cases in school-age kids did.

So if this pattern is sustained, and you think this whole thing is a testing artefact caused by people not wanting to test before going on holiday, you may now need to explain why the parents stopped testing roughly one infection cycle later than the kids did.

(rather than, for example, the kids being less infected, and hence not infecting their parents as much)

Now of course this could still be caused by some schools being off this last week (e.g. in Leics & Notts, private schools, some others taking 2-week half terms)…

https://twitter.com/Neesh_bloggs/status/1452671003918798856?s=20

…or by some schools having year groups closed for public health reasons. And to be clear I haven’t tried to estimate either of these effects, so welcome input from anyone who has.

https://twitter.com/karamballes/status/1452666586733613058?s=20

But my intuition is that neither of those effects is large enough to cause the falls in case growth that we’re seeing here, so my sense is that the primary driver is immunity, from a combination of infection plus vaccination.

(I’d much prefer that we’d reached this point with a higher % of vaccination in kids, and less infection. But the fall in cases will be welcome nonetheless, and hopefully will go further and spread through the age groups over half term). 🤞 for more good news tomorrow. /end

@Coronavirusgoo1 this might be up your street

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh