This tweet by a finance economist on climate policy & transport fuel price increases has been getting a lot of attention on German Twitter.

I am doing a THREAD about it because it's got some truth in it, but it's also misleading in several respects

I am doing a THREAD about it because it's got some truth in it, but it's also misleading in several respects

First of all, how do people respond to fuel price increases? Do they keep driving just as before, and cut expenses elsewhere?

Energy & transport economists have concept for it: the price elasticity of fuel demand.

It ranges from 0 (no fuel demand reduction) to (-)1

Energy & transport economists have concept for it: the price elasticity of fuel demand.

It ranges from 0 (no fuel demand reduction) to (-)1

Höfgen's tweet implies that the price elasticity of fuel demand is 0. Empirical research, however, comes to different conclusions. This study for Germany estimates it at 0.45

iaee.org/en/publication…

iaee.org/en/publication…

If elasticity is higher than 0 that means that a CO2 price will reduce transport emissions to some extent.

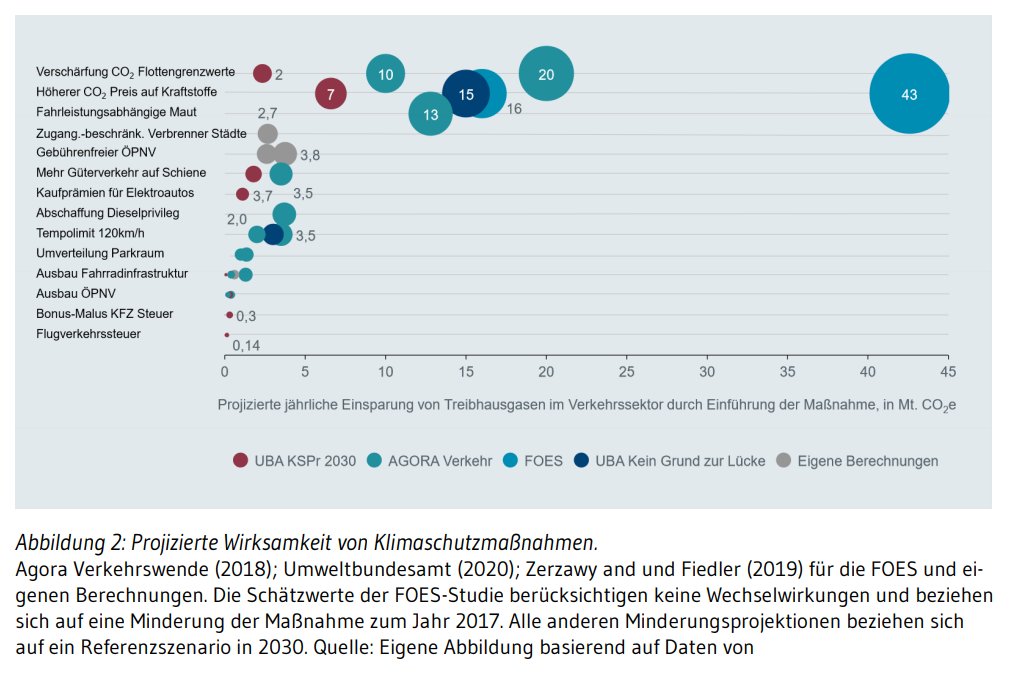

And indeed studies on the impact of a CO2 fuel tax in Germany estimate a reduction in transport emissions between 7 and 16 MtCO2 (see report ariadneprojekt.de/media/2021/10/…)

And indeed studies on the impact of a CO2 fuel tax in Germany estimate a reduction in transport emissions between 7 and 16 MtCO2 (see report ariadneprojekt.de/media/2021/10/…)

So the statement that fuel price increases "help the climate exactly ZERO" is seriously misleading. It seems to be based on an assumption of price elasticity = 0 that is at odds with empirical evidence.

Now to the kernel of truth: the price elasticity of fuel demand varies depending on a lot of factors.

In this paper we reviewed the literature on it & suggested that it ranges from 0.1 in the most car-dependent rural areas to 0.5 in European cities

doi.org/10.1038/s41558…

In this paper we reviewed the literature on it & suggested that it ranges from 0.1 in the most car-dependent rural areas to 0.5 in European cities

doi.org/10.1038/s41558…

So Höfgen's scenario of fuel price increases resulting in no reduction of car use applies perhaps to the most car-dependent rural areas. But not to many other areas where people live. In the latter, people will reduce car driving to some extent.

The problematic assumption seems to be - in plain language - that all travel by car is *necessary* and has *no alternatives*. In practice, that is not the case: a lot of car use has alternatives, or is "luxury" (will not be undertaken at whatever cost).

The kernel of truth is that there are *some* population groups for which things look as Höfgen's describes them: low-income, high & expenses on fuel, little ability to cut them, will end up cutting expenses in other areas.

We wrote a paper about it

We wrote a paper about it

https://twitter.com/TranspPoverty/status/990919828310515712

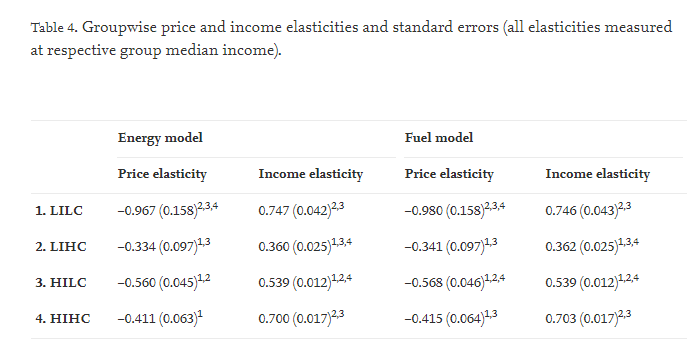

We estimated price elasticity for four different groups in the UK and find that it's pretty low (though still 0.33) among households with low income and high fuel costs, accounting for ca. 9% of the population. Elasticity is higher for the other groups though.

So how many people would belong to this 'poor & inelastic' group in Germany?

We made another study trying to identify 'forced car owners'. We find they're 7% in UK and 5% in Germany. So slightly fewer in Germany.

We made another study trying to identify 'forced car owners'. We find they're 7% in UK and 5% in Germany. So slightly fewer in Germany.

https://twitter.com/TranspPoverty/status/932933018553118720

So my guesstimate would be that the scenario described by the tweet would apply to something between 5-9% of the population in Germany. It wouldn't be accurate for the remaining 91-95%. (END)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh