The story of the rise and fall of General Electric isn't just a story of technological innovation.

It's from the start a story of financial innovation that's little less than a history of American capitalism.

Here's a column and thread:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

It's from the start a story of financial innovation that's little less than a history of American capitalism.

Here's a column and thread:

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

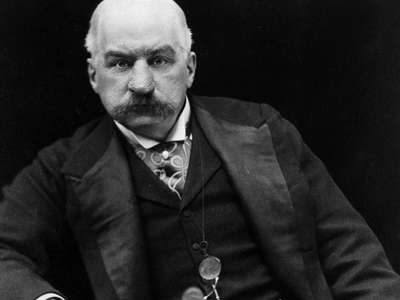

We think of the founder of GE as the great inventor Thomas Edison, but its true founder was just as much (if not more so) another crucial figure of America's Gilded Age, John Pierpont Morgan, the founder of JPMorgan.

Edison attracted Morgan's interest when he installed electricity in the financier's 5th Avenue house. J.P. Morgan was an archetypal early adopter of this brand-new technology, and quickly glimpsed its potential.

The model of Gilded Age American capitalism was to imitate John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil: Get a monopolistic position in a key industry and use it to raise prices and increase your power further.

Morgan wanted to do the same with electricity and, later, steel.

Morgan wanted to do the same with electricity and, later, steel.

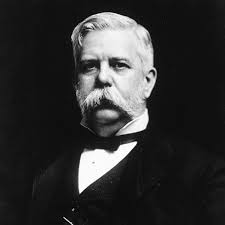

His early bet on Edison almost went disastrously wrong, though. Edison backed direct current, which was good for powering industrial motors and operated at lower voltages. His rival George Westinghouse bet on alternating current, which could operate over far greater distances.

The decisive turn came when an Edison employee called Nikola Tesla invented an alternating-current motor, removing one of direct current's key advantages.

AC was now the future. Morgan had to do a rescue merger with another firm that held AC patents to save Edison's business.

AC was now the future. Morgan had to do a rescue merger with another firm that held AC patents to save Edison's business.

That was the birth of General Electric, and Morgan's influence — the influence of finance capital — continued to be absolutely central to the business.

In the 1890s, the bond market wasn't the preserve of Wall Street Masters of the Universe. It was a retail market as open as the stock market, where brokers took off on bicycles to sell paper to farmers and storekeepers to raise funds for railways, utilities, and governments.

These retail bondholders were very keen to lend to government and major infrastructure, but they weren't so keen on industrial companies.

Morgan's solution was for GE to take control of the power sector, which *could* borrow cheaply and use the cash to buy GE's own equipment.

Morgan's solution was for GE to take control of the power sector, which *could* borrow cheaply and use the cash to buy GE's own equipment.

The Electric Bond & Share Co. that resulted rapidly became so dominant that its control of the U.S. power market, and the multi-decade struggle to break it up, is worth a whole story of its own some day.

When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, GE hit on a similar solution to maintain purchases of the electrical appliances households no longer had the cashflow to buy: Set up GE Credit Co. to provide them with loans.

Along with General Motors, GE *invented* consumer credit.

Along with General Motors, GE *invented* consumer credit.

There's a tendency to see the growth of GE Capital (the finance arm that was America's fifth-biggest lender on the eve of the 2008 financial crisis with 4% of the total market in short-term commercial paper lending) as an aberration.

In truth, it was absolutely in keeping with the oldest traditions of a business founded by America's greatest financier.

Even the conglomerate structure that the planned three-way split of GE will finally unwind was a response not to industrial pressures, but to the environment in credit markets.

When credit was scarce, lenders are unwilling to extend cash to develop small, innovative businesses.

When credit was scarce, lenders are unwilling to extend cash to develop small, innovative businesses.

The solution was to get the blue-chip giant to borrow the funds, and then follow them at below-market rates into the R&D department to develop lightbulbs, power stations, X-ray machines, electric cookers, radios, televisions, lasers, jet engines and nuclear power.

It's a supreme irony that GE's longtime CEO Jack Welch should have been the guru of the "shareholder value" movement.

Among the many problems with that philosophy is the fact that GE of all companies was about *bondholder value*.

Among the many problems with that philosophy is the fact that GE of all companies was about *bondholder value*.

The interests of risk-averse bondholders and return-hungry shareholders should always be in tension. In trying to be all things to all investors, GE ended up being neither.

Ultimately, the business model has grown old along with the population who've financed it. The life expentancy of the US population in 1900 was 48; it's now nearly 80. All those retirees living off their savings mean that credit is vastly more abundant now than it was then.

There's $13 trillion in bond trading at a negative yield now. Who cares about your triple-A credit rating when people will pay you for the privilege of lending you money?

Conglomerates haven't disappeared. Apple, Amazon or Berkshire Hathaway are quite as diversified as GE ever was, as my colleague @blsuth has often written.

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

bloomberg.com/opinion/articl…

@blsuth But unlike GE, those three companies are notably debt-averse, holding net cash through most of their histories.

@blsuth The final irony comes from a company named after Edison's arch-rival, the mercurial, irascible Nikola Tesla, making the electric cars that he tried and failed to develop, fueled by junk bonds and hubris.

@blsuth Before a stock slump last week driven by this poll on Elon Musk's Twitter account, Tesla's market cap was briefly worth more than ten times all the shareholder value that Edison, Morgan, Welch, Culp and 130 years of innovation had put together.

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1457064697782489088?s=20

@blsuth “The first thing is character, before money or property or anything else,” J.P. Morgan once said. “A man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.”

In that, as in so much else, GE now seems like a relic of a bygone age.

In that, as in so much else, GE now seems like a relic of a bygone age.

@blsuth That's the end of GE's story, but it's worth noting that the conglomerate model it pioneered is still dominant elsewhere in the world, although it's fading there too.

@blsuth Toshiba is splitting into three companies at almost exactly the same time as GE: bloomberg.com/news/articles/…

It's not been noted all that much, but Toshiba was originally effectively GE's Japan unit, licensing its patents for use over there and with GE owning a substantial stake.

It's not been noted all that much, but Toshiba was originally effectively GE's Japan unit, licensing its patents for use over there and with GE owning a substantial stake.

@blsuth Japan's keiretsu/zaibatsu business combines were set up for precisely the same reason of getting around the problems of capital scarcity, to the extent that each industrial group had its own bank that was dedicated to providing it with finance.

I suspect the conglomerate model hasn't disappeared for good.

Instead, it will emerge wherever capital scarcity and monopolistic reach provide the conditions for it to flourish.

GE may be dead, but its heirs will be with us for generations to come. (ends)

Instead, it will emerge wherever capital scarcity and monopolistic reach provide the conditions for it to flourish.

GE may be dead, but its heirs will be with us for generations to come. (ends)

BTW, if you liked this thread do follow @blsuth and read her columns. There is no better follow if you want to trace the current state of America's industry and conglomerates.

@blsuth 🤔

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh