In the Cold War there were useful idiots. In the internet era, we now have useful influencers. Check out our deep dive into a new crop of social media personalities that get major support from China to boost its image overseas. nytimes.com/interactive/20…

The rise of the influencers dates back to the protests in Hong Kong, when China first began to more aggressively push its narratives on global social media. It has returned to them again and again, to defuse criticism over Xinjiang and the early spread of the coronavirus.

So what did we find? State media and local governments pay influencers to take trips around China. They also offer payment for content sharing. The influencers say they are creatively independent.

But it's clear Beijing is using them as propaganda tools, taking advantage of the blurred line between influencer and advertiser. Stop echoing Chinese propaganda, and benefits from the government will stop too.

The influencers also give plausible deniability. On YouTube even employees of Beijing-controlled media, like Li Jingjing, are not labeled as state-affiliated media if they set up a personal account. On YouTube her account looks independent, on Twitter she gets a label.

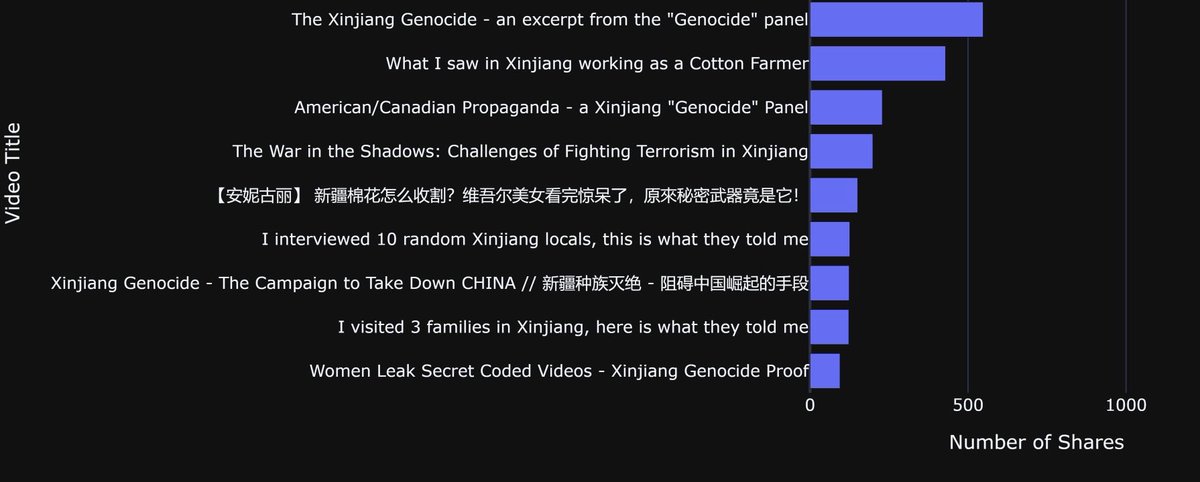

Perhaps just as important as money, the influencers are widely shared by China's hugely followed state media and diplomatic Facebook and Twitter accounts. Here's a spike in YouTube video shares as China began arguing back against accusations of forced labor in Xinjiang.

One video by Israeli influencer Raz Gal-Or portraying Xinjiang as "totally normal" was shared by 35 government connected accounts with a total of 400 million followers. Many were Chinese embassy Facebook accounts, which posted about the video in numerous languages.

Raz also got help from what appeared suspiciously like a coordinated information operation. Darren Linvill of Clemson showed of the 534 accounts tweeting the video from April through June, 40% had 10 or fewer followers.

This has helped the YouTube videos dominate discussion on platforms like Twitter. Two Yale researchers looked at a sample of 290k tweets that mention Xinjiang in the first half of 2021. Six out of the 10 most shared YouTube videos were from pro-China influencers.

State media appears to be doubling down on the approach. State broadcaster CGTN has its own landing page for influencers, happily called gstringers for global stringers. It boasts 744 around the world. It explicitly offers bonuses and publicity for those who join up.

A talent contest it ran earlier this year, subtly called the Media Challengers, also sought to surface a new generation of talent. Here's one of the finalists: news.cgtn.com/news/2021-08-2…

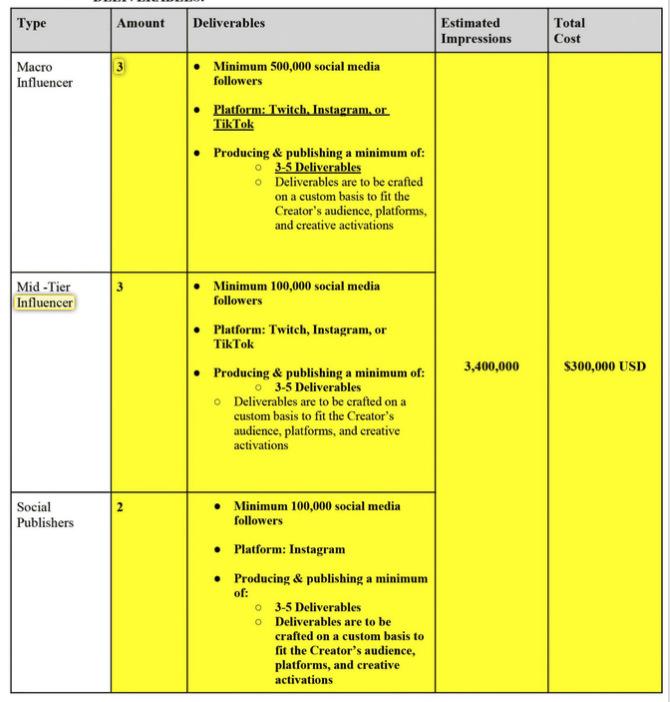

A FARA filing shows China's consulate general in the US is paying $300,000 to a firm to recruit influencers to put out China friendly content during the upcoming winter Olympics. It all types, from celebrity influencer to nano influencer. opensecrets.org/news/2021/12/c…

So what is the ultimate point? Many won't believe the influencers outright. But they do help muddy the waters. A good example comes from a trip to Xinjiang by fledgling influencer Noel Lee.

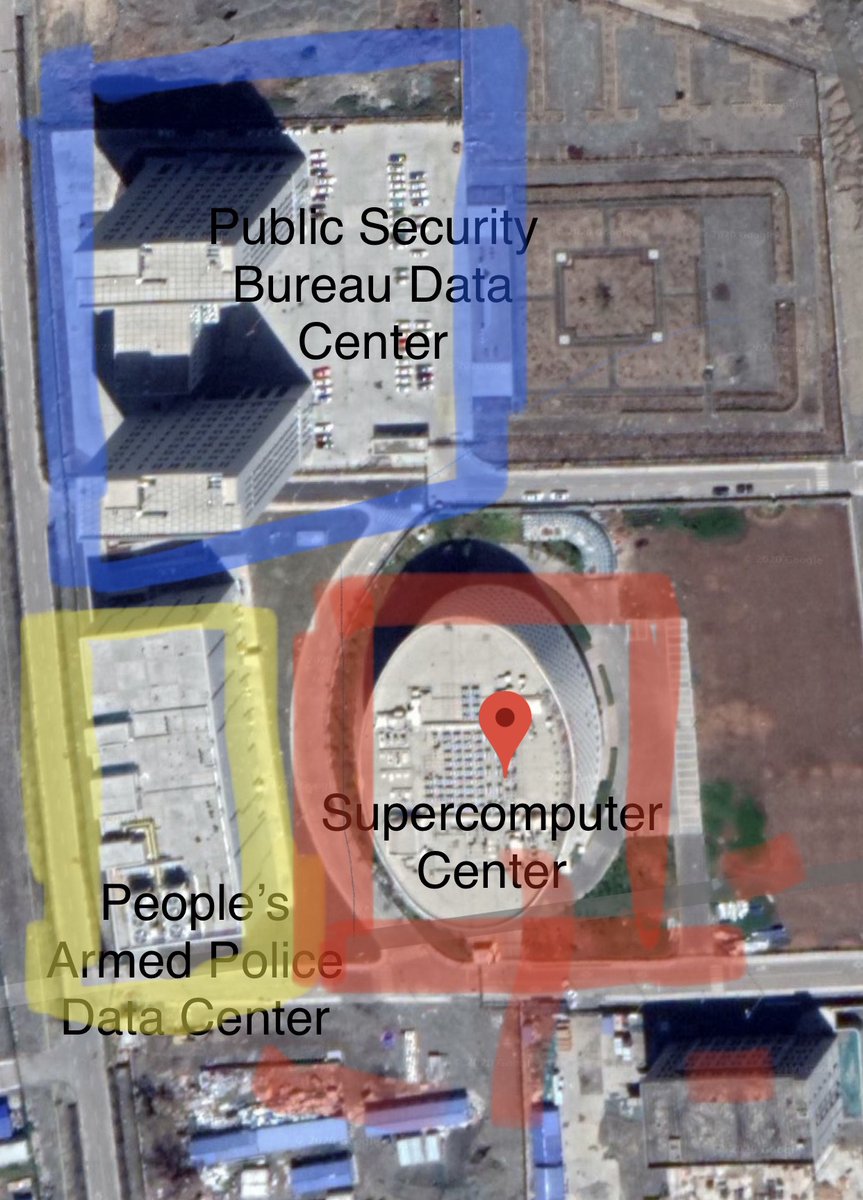

He opines that from a plane no one could figure anything out about the structures below, an attempt to undercut satellite images of a sprawling system of re-education camps. A new ASPI report shows, he inadvertently captured several camps:

https://twitter.com/fryan/status/1470614895834005506?s=20

As former censor Eric Liu told us, it's all about creating doubt in those who don't follow any of this closely: “The goal is not to win, but to cause chaos and suspicion until there is no real truth.”

nytimes.com/interactive/20…

nytimes.com/interactive/20…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh