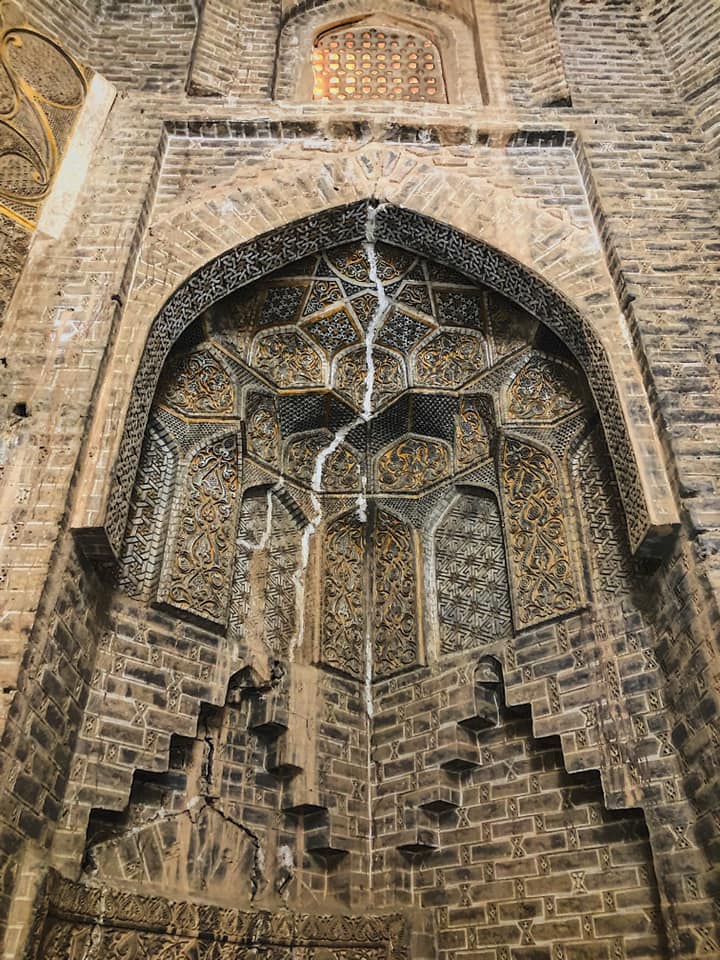

Imamzadeh Yahya, a beautiful shrine in Varamin, near Tehran, Iran, dating back 700+ years.

Notice the white gaps between the wall tiles.

What you see is a holy place stripped of its beauty by Western archaelogists.

A thread about archaeology, colonialism, museums, and theft:

Notice the white gaps between the wall tiles.

What you see is a holy place stripped of its beauty by Western archaelogists.

A thread about archaeology, colonialism, museums, and theft:

In the 1800s, Western archaeologists began excavating in Iran.

The French pressured Iran, weak and indebted, to give it a monopoly.

This allowed them to take half of what they found.

Religious sites were exempted.

Yet, Imamzadeh Yahya was pillaged. ALL tiles were stolen.

The French pressured Iran, weak and indebted, to give it a monopoly.

This allowed them to take half of what they found.

Religious sites were exempted.

Yet, Imamzadeh Yahya was pillaged. ALL tiles were stolen.

Hundreds of lustrous tiles once covered the shrine's wall, many from the 1200s.

They were stripped and stolen by archaeologists, spirited away to Western museums.

This is what those tiles looked like.

These images are taken from the sites of the museums that keep them today.

They were stripped and stolen by archaeologists, spirited away to Western museums.

This is what those tiles looked like.

These images are taken from the sites of the museums that keep them today.

In the late 1800s, after being robbed of its tiles, locals in Varamin began purchasing new tiles to cover the shrine's walls.

Those are the blue and yellow tiles on the shrine today.

But notice how the replacements installed after the theft barely fill the gaps in the wall.

Those are the blue and yellow tiles on the shrine today.

But notice how the replacements installed after the theft barely fill the gaps in the wall.

Original tiles were smuggled out of Iran. Today they are found in museums around the world- Chicago, St. Petersburg, London, Honolulu.

The whole world has a piece of Varamin, while the original shrine sits stripped of its past beauty.

brill.com/view/journals/…

The whole world has a piece of Varamin, while the original shrine sits stripped of its past beauty.

brill.com/view/journals/…

Here is the mihrab of the shrine.

It was lifted in its entirety, and today its beauty graces a museum - in Hawaii.

In a country that is nearly impossible for most Iranians to visit.

They stole Iran's beauty, but would rather not see actual Iranians.

islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.…

It was lifted in its entirety, and today its beauty graces a museum - in Hawaii.

In a country that is nearly impossible for most Iranians to visit.

They stole Iran's beauty, but would rather not see actual Iranians.

islamicart.museumwnf.org/database_item.…

Archaeologists were supposed to document the shrine; instead, they stole.

Today, museums continue to benefit.

Some claim artifacts must be removed to be preserved.

But the shrine is lovingly taken care of. Iran has carried out extensive preservation work over the years.

Today, museums continue to benefit.

Some claim artifacts must be removed to be preserved.

But the shrine is lovingly taken care of. Iran has carried out extensive preservation work over the years.

Discussions abt decolonizing museums often happen in a world of "what ifs," as if the places objects come from are long gone.

But many are still standing: in their homeland, stripped of their beauty.

Remember that when you see beautiful objects in museums from far away places.

But many are still standing: in their homeland, stripped of their beauty.

Remember that when you see beautiful objects in museums from far away places.

All the talk of "preservation" is ironic because many artifacts taken from the Middle East were damaged in Europe during World War II.

Numerous museums in Berlin were bombed and/or pillaged in the war.

People forget that Europe is not outside history.

Numerous museums in Berlin were bombed and/or pillaged in the war.

People forget that Europe is not outside history.

After World War II, the Soviet Union returned many of the objects that the Red Army stole from Berlin's museums.

Isn't it ironic? The Soviets returned stolen objects to Germany.

But when will Europe take seriously the question of the objects stolen from the rest of the world?

Isn't it ironic? The Soviets returned stolen objects to Germany.

But when will Europe take seriously the question of the objects stolen from the rest of the world?

For more on Imamzadeh Yahya shrine and its history, read this excellent article by Keelan Overton and Kimia Maleki.

"It is no secret that much of the “Islamic art” on display in global museums exists in a fragmented and decontextualized state."

brill.com/view/journals/…

"It is no secret that much of the “Islamic art” on display in global museums exists in a fragmented and decontextualized state."

brill.com/view/journals/…

This thread is deeply indebted to that article, which gives an analysis of how Varamin's tiles became so important in the world of art history - and asks what justice would look like for the shrine itself, which is still a working religious site near Tehran.

For a history of the politics of archaeology in Iran, I highly recommend this article:

"Nationalism, Politics, and the Development of Archaeology in Iran" by Kamyar Abdi"

jstor.org/stable/507326

"Nationalism, Politics, and the Development of Archaeology in Iran" by Kamyar Abdi"

jstor.org/stable/507326

Beyond the shrine, Varamin is also a fascinating place.

This gorgeous tower sits in the town's main plaza, with a garden shop beside it, at the heart of Varamin.

It's the tower of Alaa ol-Dowla, a Seljuk-era funerary monument from over 800 years ago.

This gorgeous tower sits in the town's main plaza, with a garden shop beside it, at the heart of Varamin.

It's the tower of Alaa ol-Dowla, a Seljuk-era funerary monument from over 800 years ago.

And just outside Varamin, amid quiet farm fields, rises the 2,000-year old Citadel of Iraj, once the largest fortress in the Middle East.

Stretching across the horizon, it’s mudbrick walls reach 50 feet high in places.

Each side of the fort is an astounding 1,500 meters.

Stretching across the horizon, it’s mudbrick walls reach 50 feet high in places.

Each side of the fort is an astounding 1,500 meters.

Once upon a time, the walls were full of rooms and chambers, whose doorways still peak out.

Varamin is thought to be the ancient city Varena, one of the great settlements of the Sassanian world and mentioned in the Avesta, the Zoroastrian holy book.

Varamin is thought to be the ancient city Varena, one of the great settlements of the Sassanian world and mentioned in the Avesta, the Zoroastrian holy book.

These images of the fort from above and its wall are from this article, “Largest Ancient Fortress of Southwest Asia and the Western World? Recent fieldwork at Sassanian Qaleh Iraj at Pishva.”

Original:

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

Non-paywall version:

academia.edu/43970061/Large…

Original:

tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.108…

Non-paywall version:

academia.edu/43970061/Large…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh