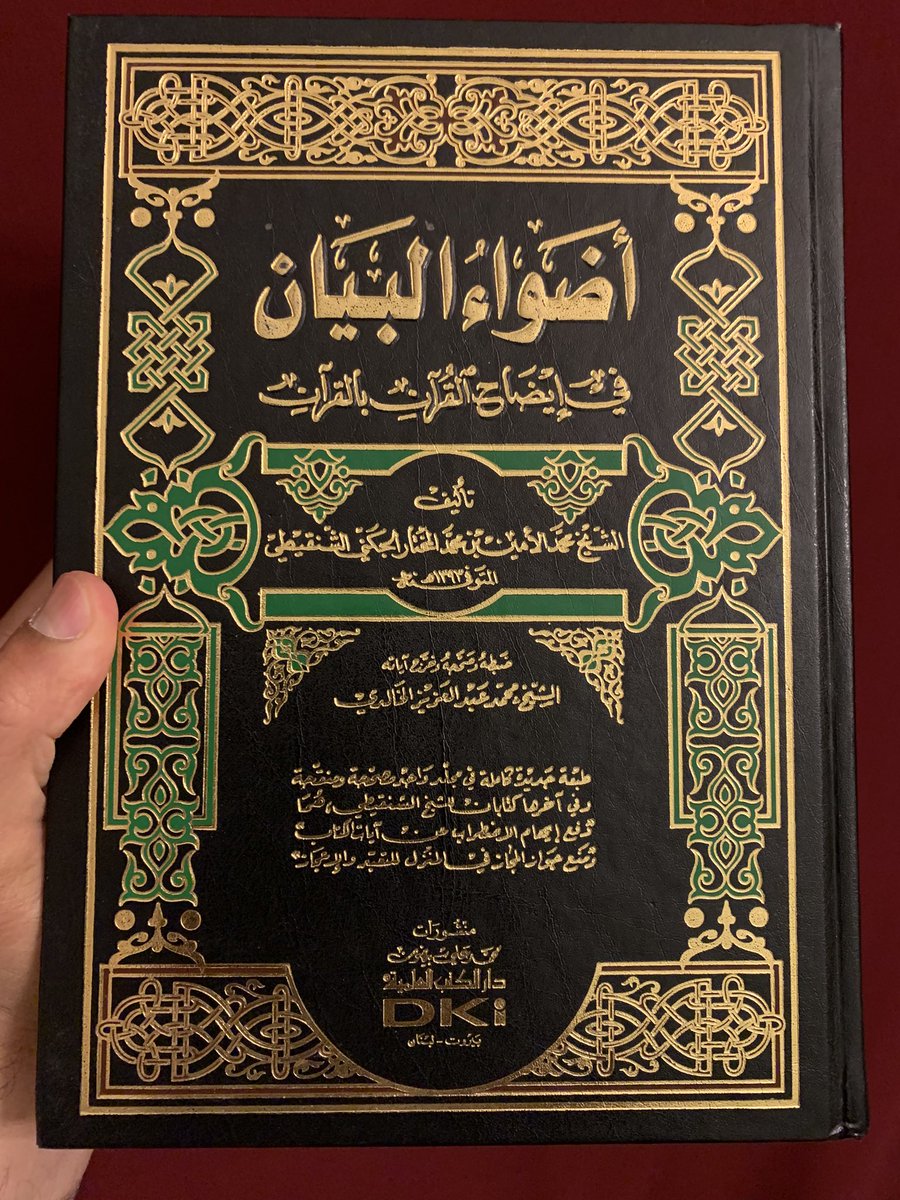

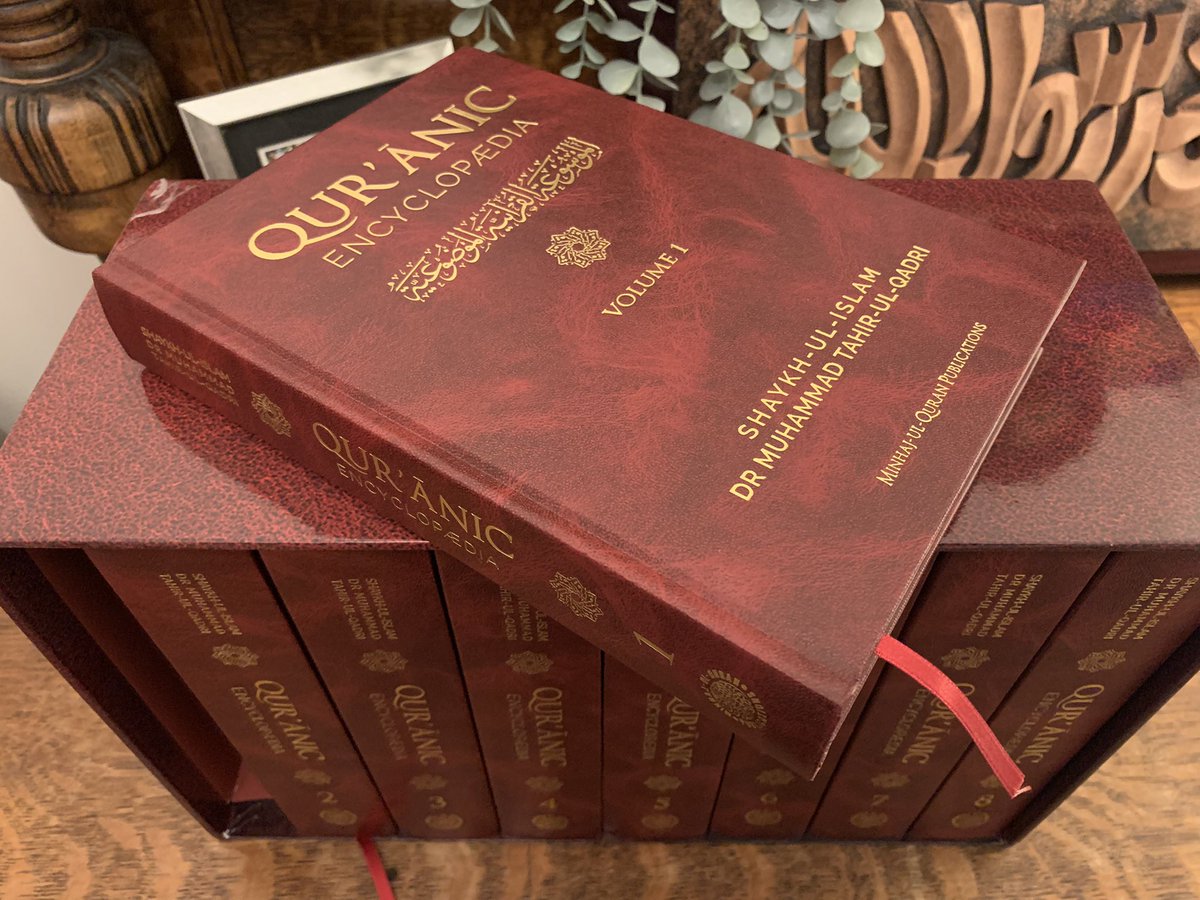

Publishers sent me a complimentary copy of this Qur’anic Encyclopædia by Dr M. Tahir-ul-Qadri – may Allah reward them! I’ll share brief first impressions, then say a little on a theological/exegetical issue that caught my eye.

After vol. 1 which is a detailed contents list, there are two parts. Vols. 2-5 present individual ayat under thematic subheadings with translation. This could be suitable for looking up topics, or going through systematically in addition to reading a standard mushaf/translation.

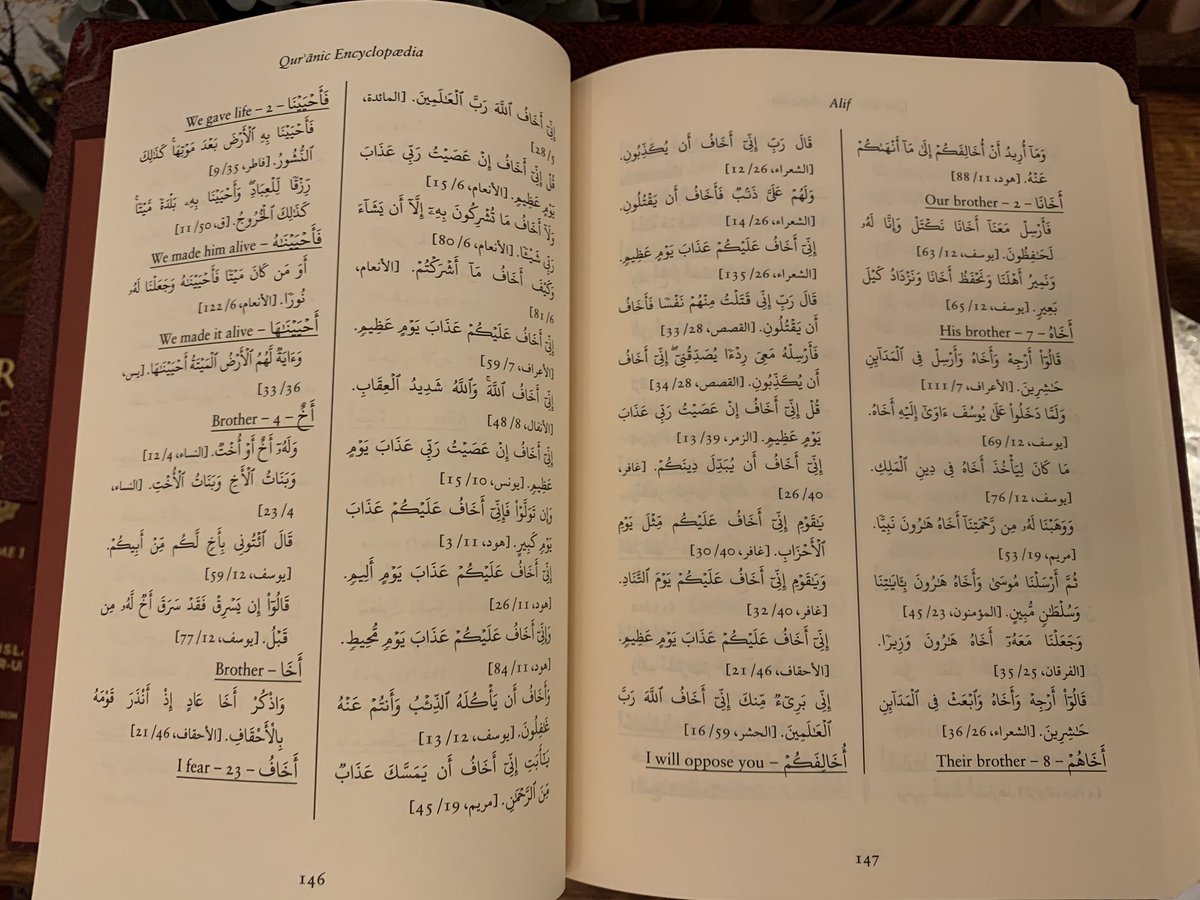

Then vols. 6-8 are a “Comprehensive Index of Qur’anic Words” drawing upon ‘Abd al-Baqi’s المعجم المفهرس and other lexical works. It’s arranged alphabetically, not by root: see here how that looks (unrelated words can appear among different occurrences of “brother”).

I can see this being of use to English readers, though nowadays there are easier ways of getting such data at your fingertips rather than thumbing through thick volumes. The typesetting could also have been more compact to reduce the whole work’s bulk.

I also feel that “encyclopaedia” isn’t the right description for this work (or rather, these 2 works). There isn’t a range of scholarly entries under each topic, though there are footnotes. Let’s look at one example now.

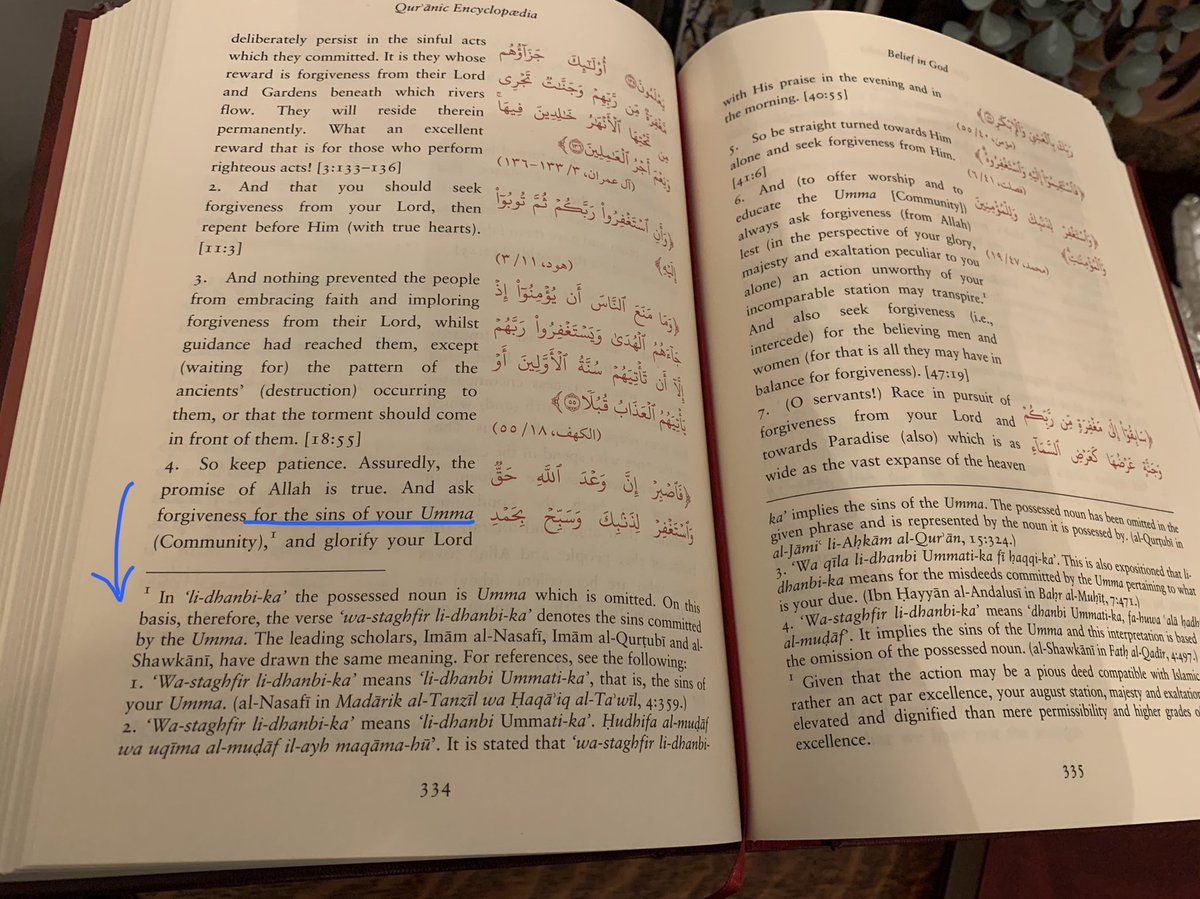

This was literally the first page that fell open for me, not an issue I go searching for! But I know it’s a hot topic for many, and even a litmus test some use for translations (whether they are “orthodox” or not).

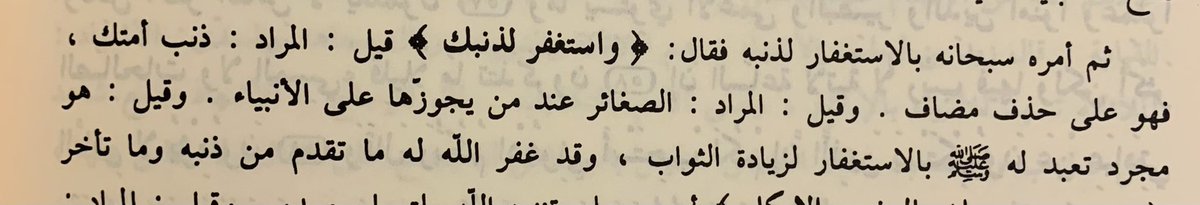

The question is how to understand the phrase واستغفر لذنبك (literally: seek forgiveness for your sin) when addressing the Prophet ﷺ.

You can see a related thread on Q 48:2 here, and this article gives some good background:

You can see a related thread on Q 48:2 here, and this article gives some good background:

https://twitter.com/tafsirdoctor/status/1216849392826769409

My aim here isn’t to prove one view, and certainly not to engage in sectarian squabbles – if you’re looking for that, move along! There’s no drama here. Rather, I’m interested in how the sources have been used and quoted.

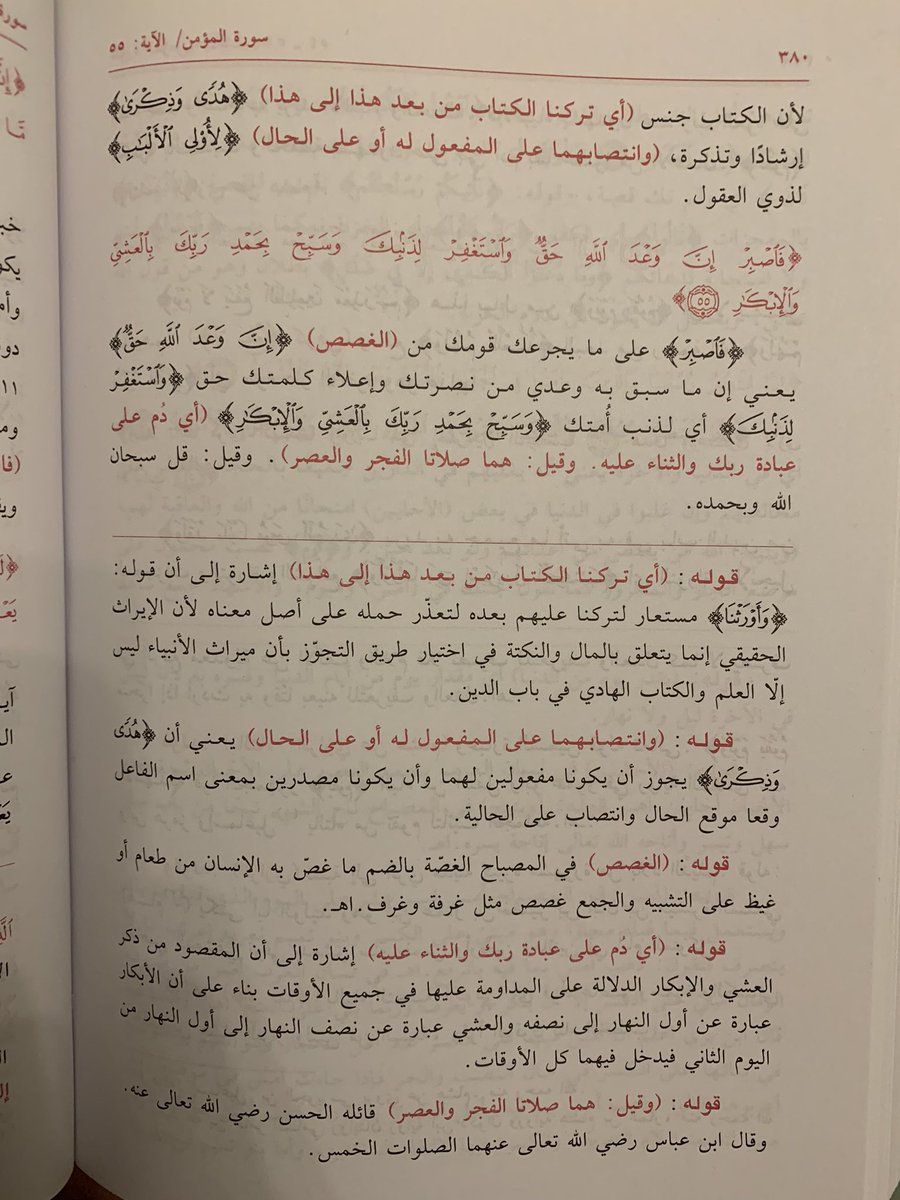

Let’s start with Nasafi. Indeed, that’s the only view he mentions here. And the hashiya (al-Iklīl) doesn’t add anything.

[Nasafi clearly wasn’t happy with Zamakhshari on this point, though he follows him in most of the tafsir. Here, Z glosses it: استدراك الفَرَطات بالاستغفار – editors of one edition I consulted say that by these “slips” he means ترك الأولى choosing something lawful but suboptimal.]

Once we look at the other references, we start to see that this is one explanation among several! And we should ask why only these sources are cited: what do other mufassirs say?

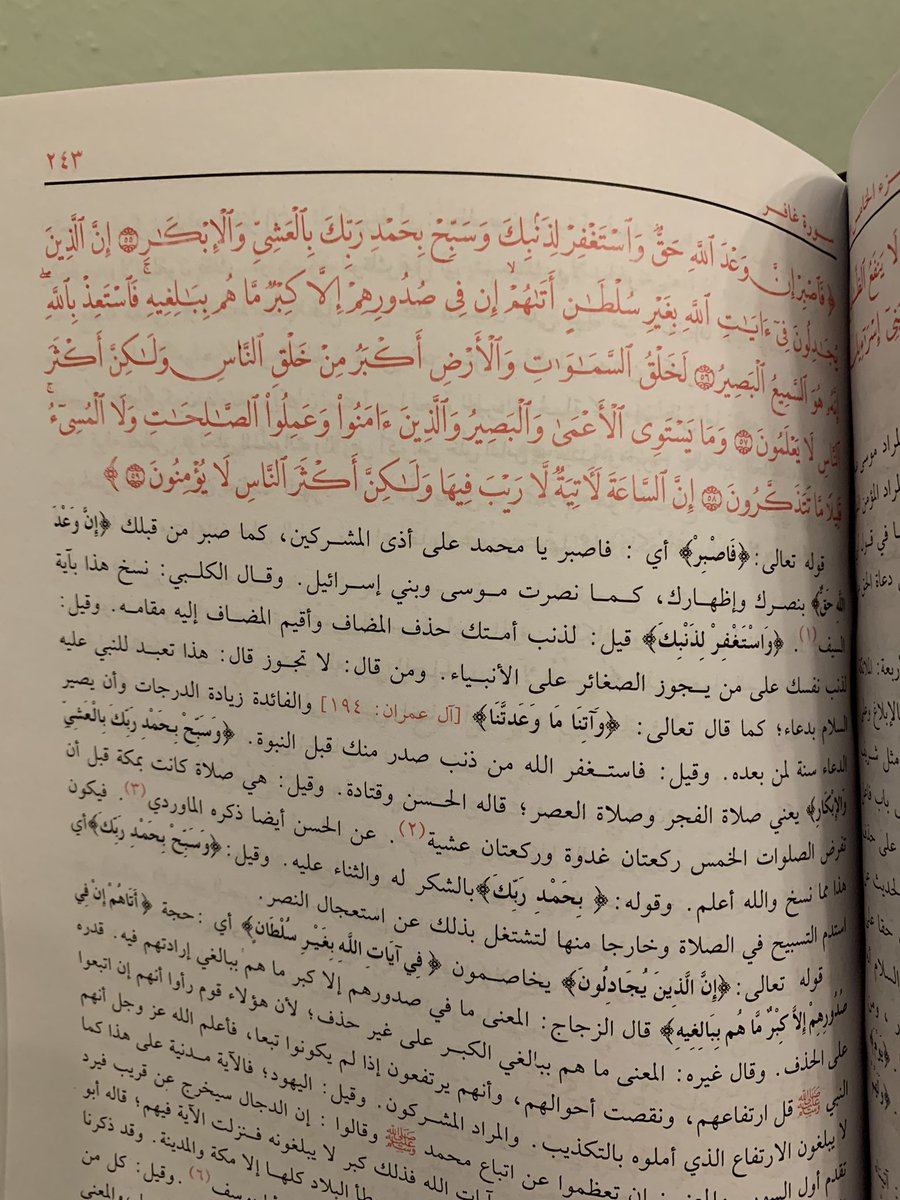

Let’s see Qurtubi. I see here that actually he gave this as one قيل among others, not necessarily his preferred explanation. He mentions those who consider it possible for a prophet to commit minor sins. Or that it refers to the time before being called as a prophet. Or it’s…

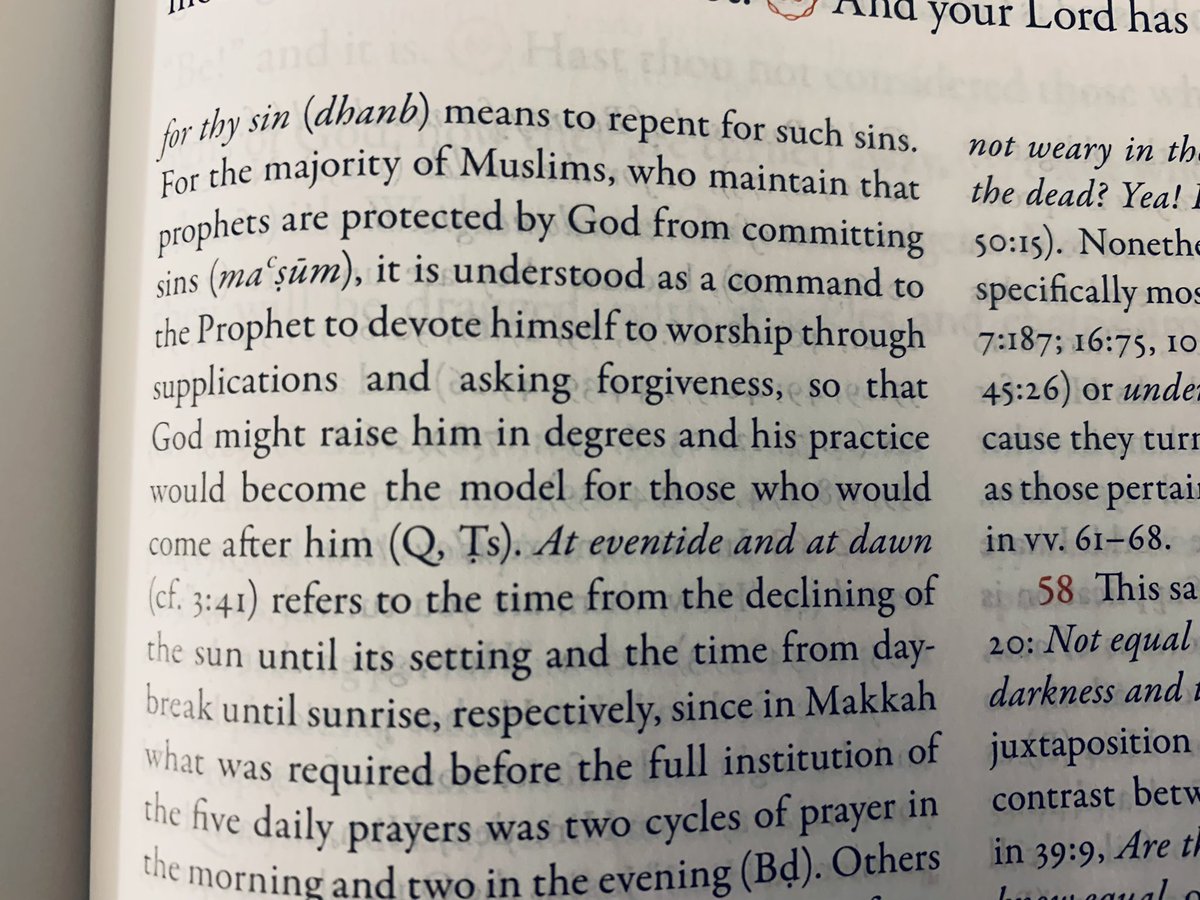

an instruction just to have the reward of beseeching God (though there is so sin), just like we’re taught to say “Lord, give us what You promised us” (3:194) even though there’s no actual need once He already promised!

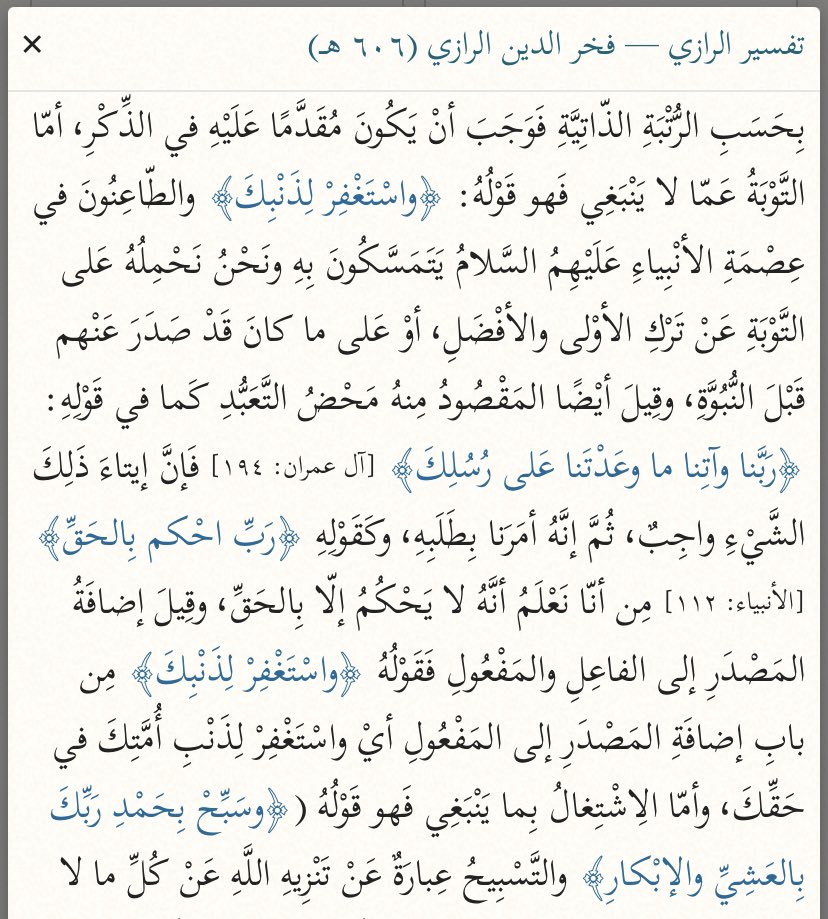

Then comes Abu Hayyan, and the word قيل is actually acknowledged in the Encyclopaedia’s footnote this time. Interestingly, AH is quoting Razi on this point, so he really should have been cited (he precedes even Nasafi & Qurtubi).

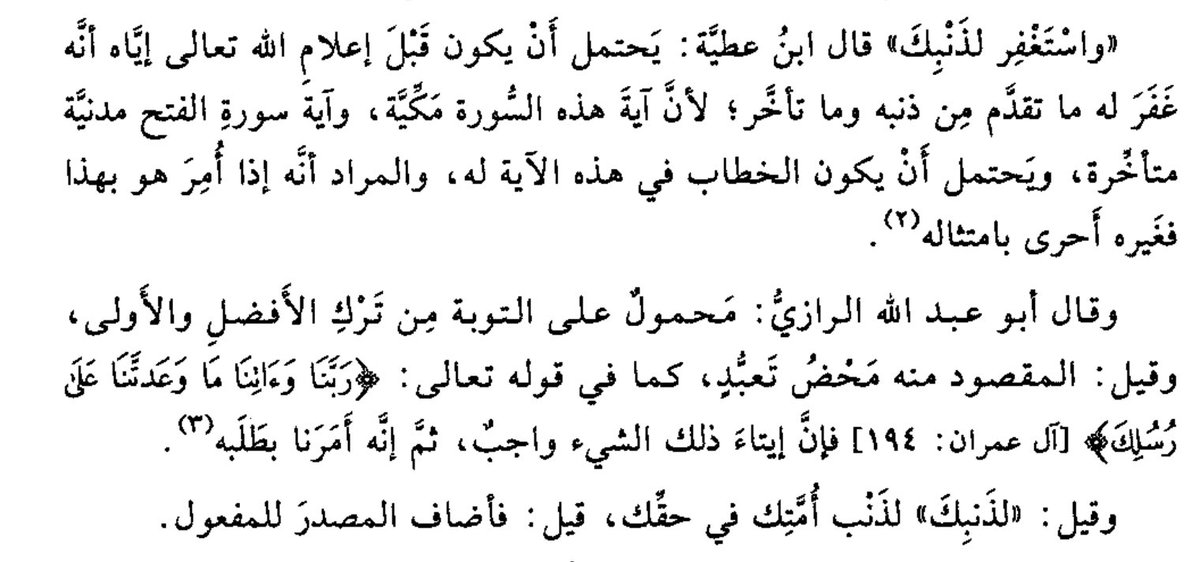

Razi provides the clearest explanation of the “sin of your nation” explanation. He starts by saying that the verbal noun ذنب could either be annexed to its subject (hence “the sin by you”)…

or its object (“the sin against you”). Here the gloss is supplied: ذنب أمتك في حقك.

I find this more plausible than the claim that there’s simply an elided mudaf (as in Nasafi et al).

I find this more plausible than the claim that there’s simply an elided mudaf (as in Nasafi et al).

Shawkani is unremarkable here, the same few possibilities outlined. Maybe he was cited for ideological diversity(?) – but again the fact it’s a قيل for him should have been mentioned.

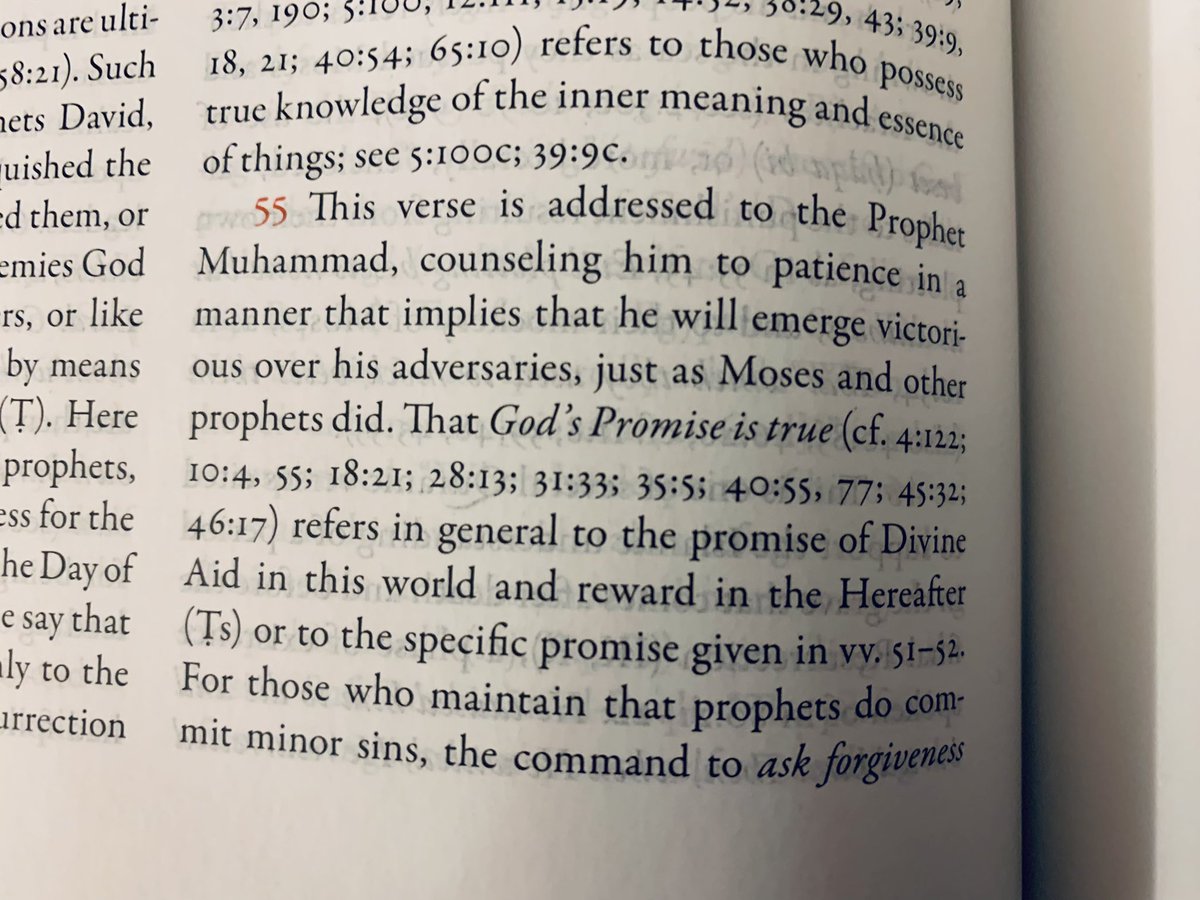

In closing, to be fair, I should say that the work doesn’t claim to be encyclopaedic in covering these topics and sources. And even the Study Quran is quite brief on the matter. Notice that Q(urtubi) is cited here for a different opinion!

That’s in line with the usual SQ practice of citing the reference where the opinion is mentioned. I’d like to see in future works that clearer distinction is made between an exegete’s own views and those he happens to mention.

/end

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh