I am begging people who get people to repeat the Shahada after them (especially if they do it on video dressed as an Azhari) to please get the wording right!

أشهد ألّا (أن لا) إله

Not “anna lā”!

أشهد ألّا (أن لا) إله

Not “anna lā”!

Anna أنّ needs to have an ism, like you see clearly in the second half:

وأشهد أنّ محمداً ﷺ رسولُ الله

So in theory, it’d make sense to say:

وأشهد أنّ محمداً ﷺ رسولُ الله

So in theory, it’d make sense to say:

[أشهد أنّ اللهَ لا إله إلا هو]

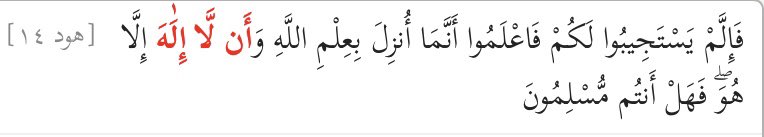

But that’s not how we received it. There’s another way that would also work, and this is actually relevant. It involves something called ضمير الشأن:

But that’s not how we received it. There’s another way that would also work, and this is actually relevant. It involves something called ضمير الشأن:

[أشهد أنّه لا إله إلا الله]

The ism here isn’t for Allah ﷻ but gives the meaning (if you’re really spelling it out):

“I testify that *it’s the case that* there is no god except Allah.”

The ism here isn’t for Allah ﷻ but gives the meaning (if you’re really spelling it out):

“I testify that *it’s the case that* there is no god except Allah.”

That’s the proper way to get from the particle أنّ to the negating لا. But we can also use a lightened form: أنْ which stands in for أنّ+اسم.

(Note: not all أنْ is of this type!)

(Note: not all أنْ is of this type!)

So this gives us أشهد أنْ لا – then we notice that in pronunciation, we merge that unvowelled nūn into the lām. Hence it’s also accepted to write this in a merged form like this (though there’s a bunch of detail on that we don’t need here).

أشهد ألّا إله إلا الله

🕋

أشهد ألّا إله إلا الله

🕋

I meant to say here: the pronoun (-hu) isn’t referring to Allah ﷻ. But hopefully you got the point.

https://twitter.com/tafsirdoctor/status/1476521186091745280

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh