“Spooked zebras”?

An enquiry into the language, readings & translation of Q. 74:50

كأنهم حمر مستنفِـَرة

An enquiry into the language, readings & translation of Q. 74:50

كأنهم حمر مستنفِـَرة

Before we get into the meaning of mustanfirah/mustanfarah, let’s clarify what species we have here. The exegetes clarify it is “wild donkeys/asses”, also called onagers. Though the term حمر الوحش is nowadays used for zebras, those weren’t known to the Arabs of the time.

Therefore it’s not the right translation, and it’s a shame that after being used only by the Egyptian “Montakhab” and a few “Quranists” like Rashad Khalifa, it now appears in the popular Clear Quran translation!

[The next ayah states that the wild donkeys have fled from “qaswarah” – most exegetes (and translators) say this means a lion, but some said “hunters/archers”, among other opinions.]

The image here is about people turning away from the Message: they are compared to wild animals that are stampeding after a perceived threat has caused them to panic. Ibn ʿĀshūr points out how common this simile is in Arabic poetry.

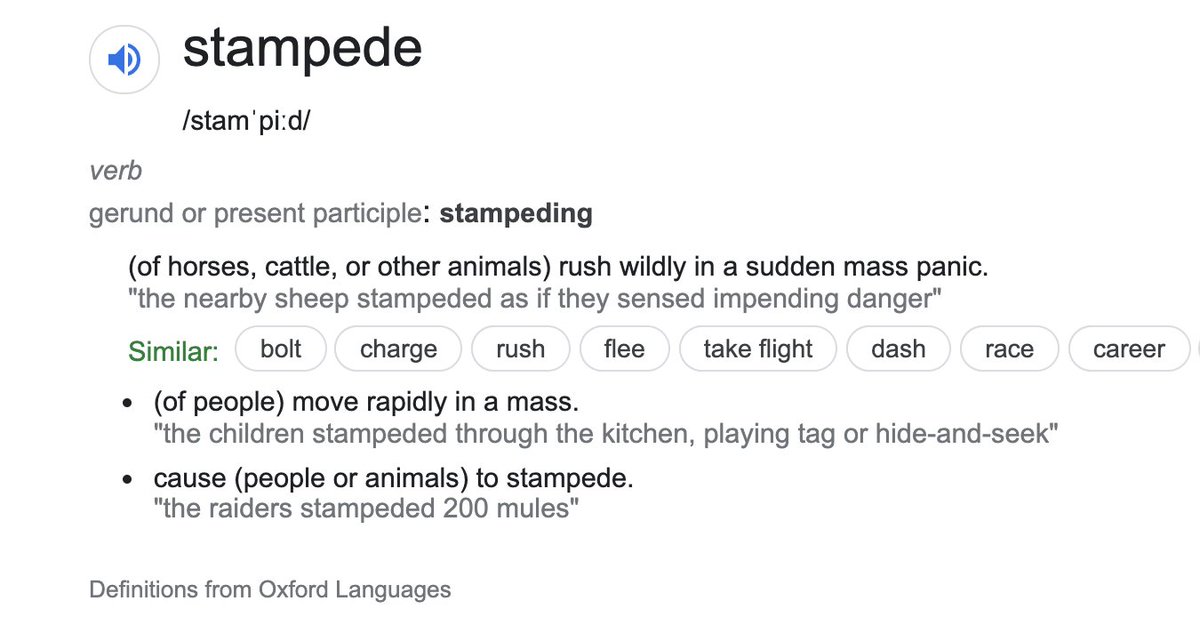

So while the root word نفار contains this sense of taking fright, it’s more directly about the subsequent dispersal and flight. The word “stampede” captures this very well. Well done Dr Ghali!

However, you generally find “frightened”, “panicked”, “startled” – with nothing to indicate their stampeding movement. This is probably because the picture becomes clear from the next ayah!

islamawakened.com/quran/74/50/

islamawakened.com/quran/74/50/

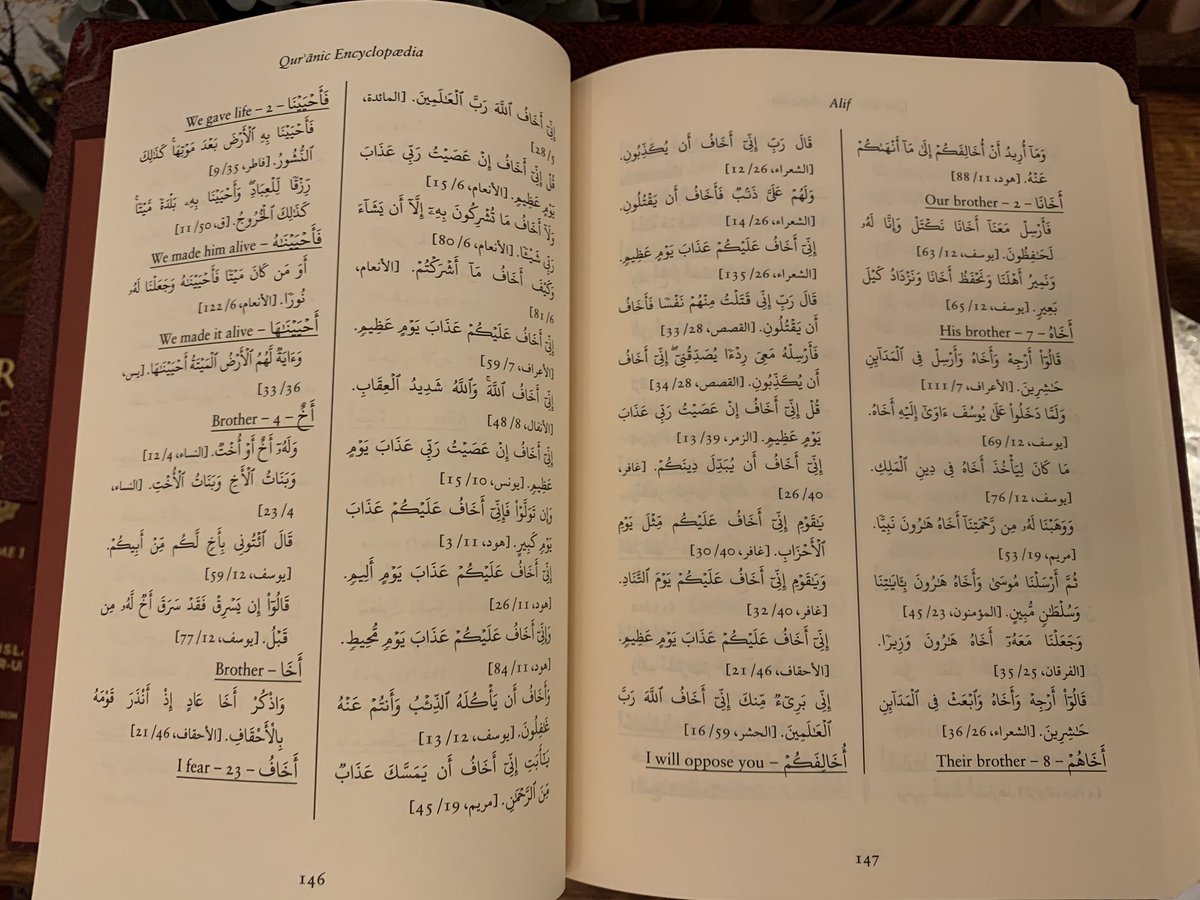

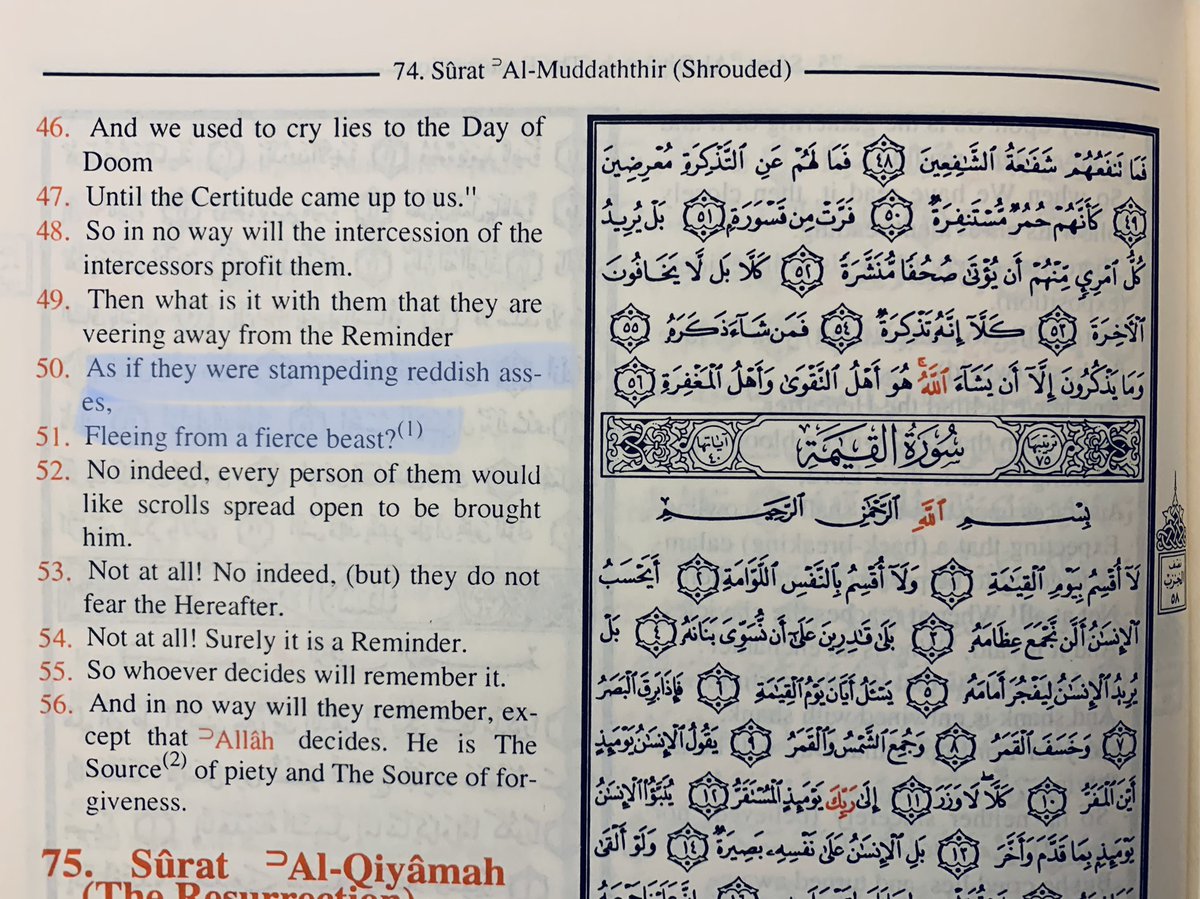

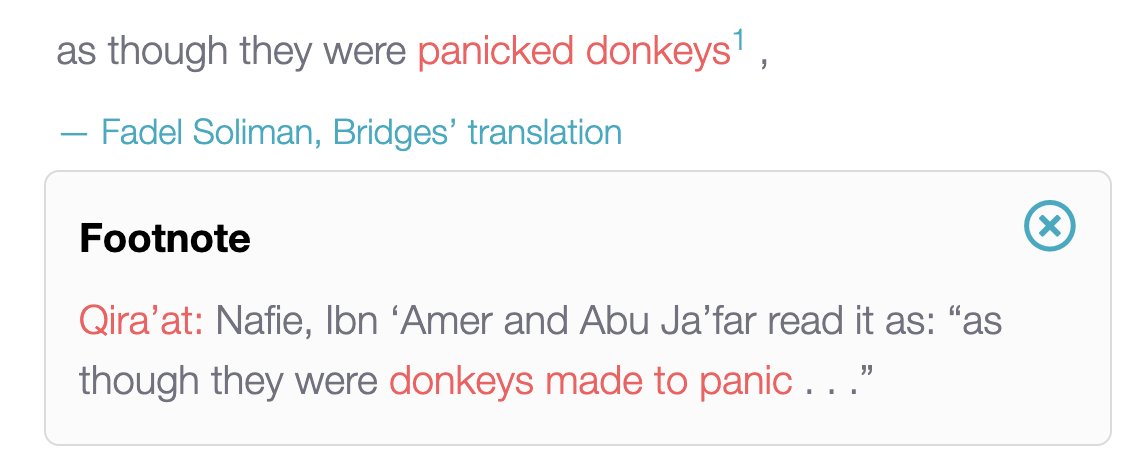

Now, the word مستنفرة is recited in two ways: mustanfirah (the majority) / mustanfarah (Nāfiʿ, Abū Jaʿfar, Ibn ʿĀmir). Technically, these are active & passive participles, respectively. But are they truly different in meaning?

Consider this attempt to translate them distinctly. Do you see how “panicked” itself is a passive word? They might have gone with “panicking” – but let’s see how the scholars of tafsīr & tawjīh discussed this difference.

Among early scholars (al-Farrāʾ, al-Ṭabarī) it seems that any difference is negligible. They are just two ways Arabs described stampeding animals, as it has these two elements (being startled, and taking flight).

Later scholars spell out the nuance: the majority reading (which the translators should be following) مستنفِرة (form X) is equivalent to نافرة (form I), or more emphatic – Zamakhsharī explains this nicely. So it’s “stampeding”.

As for مستنفَرة : it is considered equivalent to forms II/IV مُنَفَّرة مُنْفَرة “made to stampede”. But the word “stampede” also has this transitive meaning (see definition above)! So translating them distinctly seems fruitless.

I actually like Abū Ḥayyān’s take on the passive form:

اسْتَنْفَرَها فَزَعُها مِنَ القَسْوَرَة

It’s not the lion itself that’s the agent, but the donkeys’ fright. In this way, the active/passive boil down to the same thing.

اسْتَنْفَرَها فَزَعُها مِنَ القَسْوَرَة

It’s not the lion itself that’s the agent, but the donkeys’ fright. In this way, the active/passive boil down to the same thing.

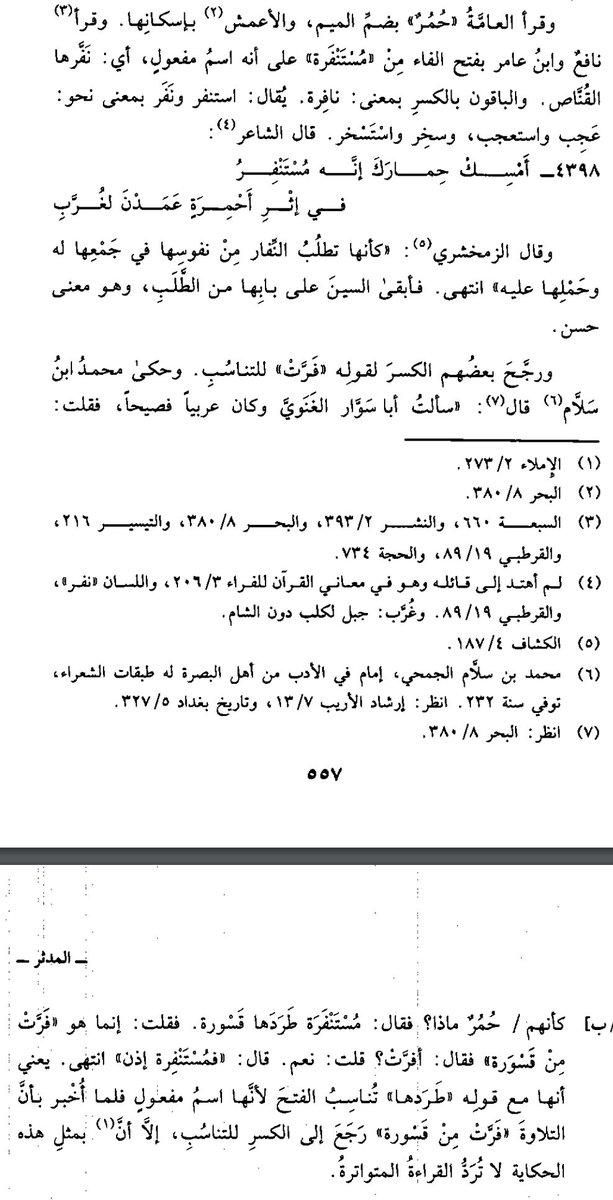

Finally, there’s an anecdote which appears in some works (see al-Fārisī’s Ḥujjah, and a slightly different wording in Ibn Khālawayh’s. Attached text/comments are from al-Samīn). An eloquent Arab was asked which of the two readings was best to his ears.

His first response was “mustanfarah” (passive). But it seems that he had thought the following phrase was “chased by a lion”. When he was told it is actually “having fled from a lion” (the donkeys being the agent of the verb), he said “In that case, mustanfirah!”

Of course, both readings make sense, but this speaker felt that the active participle matches the verb فرّت more neatly. Both are canonised readings beyond reproach.

Thanks to Faisal Qasim & Salman Nasir for discussing and clarifying some points. /end

Thanks to Faisal Qasim & Salman Nasir for discussing and clarifying some points. /end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh