Do you need to know how to graft an apple tree, how to ‘make a horse piss and dung', or need advice on making a wise choice in marriage?

John Gwin, 17th century churchwarden at Llangwm Uchaf, has the answers to all of these questions, and much more …

John Gwin, 17th century churchwarden at Llangwm Uchaf, has the answers to all of these questions, and much more …

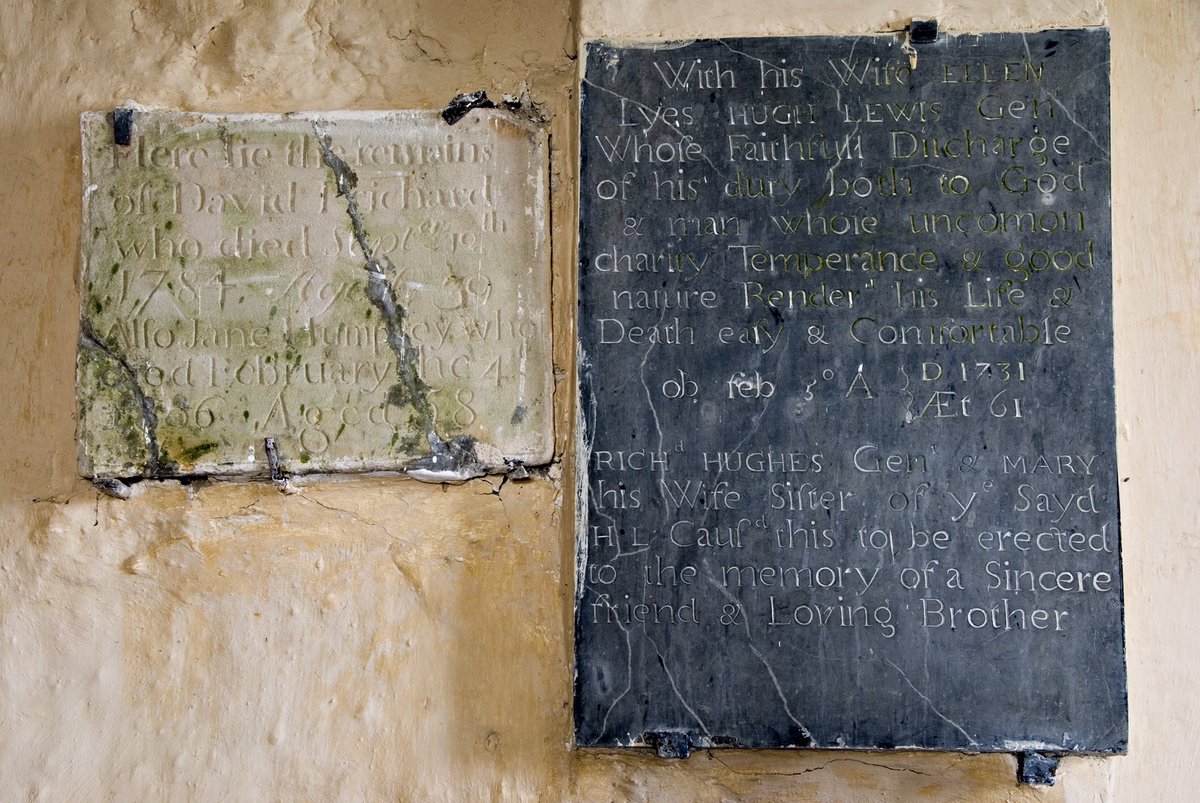

Throughout his life, John kept a 'commonplace book' — recording family affairs, local events, home improvements, advice on husbandry, poems, medical treatments, and parish politics.

It’s survived to give us a fascinating window into life in Monmouthshire in the late 1600s.

It’s survived to give us a fascinating window into life in Monmouthshire in the late 1600s.

John had a particular interest in medicine, recording cures that combined traditional and modern medical ideas. His interest wasn’t purely academic. We can imagine John’s fears as he notes the directions for treatment of his two children — 'sick of the smallpox'.

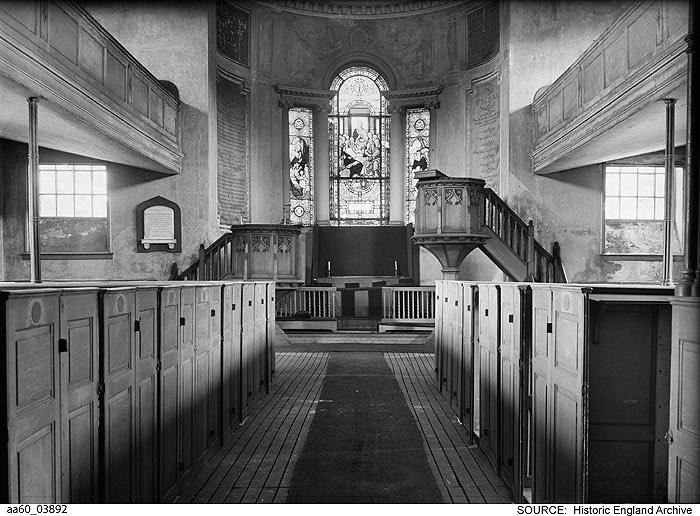

In a time of significant political upheaval it’s not surprising that much of John’s energy went into settling heated local disputes. In 1671 the parishioners of St Jerome’s quarrelled intensely over seating in the church, some ‘intruding themselves into the seetes of others.'

Tony Hopkins, former Archivist of Gwent Archives and Dr. Madeleine Gray @heritagepilgrim are preparing to publish a transcription of John Gwin’s Commonplace Book later this year.

Tony tells us more about John Gwin’s extraordinary legacy …

friendsoffriendlesschurches.org.uk/story/john-gwi…

Tony tells us more about John Gwin’s extraordinary legacy …

friendsoffriendlesschurches.org.uk/story/john-gwi…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh