our paper is now out @Nature ! nature.com/articles/s4158…

a 🧵on the excitement and value of Basic Science, DNA replication and repair, teamwork and collaboration, and the fundamental incompatibility of LEGO and DUPLO 1/n

a 🧵on the excitement and value of Basic Science, DNA replication and repair, teamwork and collaboration, and the fundamental incompatibility of LEGO and DUPLO 1/n

as a clinician scientist, a common question from those around me, as summarised by my son, is :

"why are you going in to work at the lab when you could be saving lives RIGHT NOW in the hospital?" 2/n

"why are you going in to work at the lab when you could be saving lives RIGHT NOW in the hospital?" 2/n

as an aside, childhood mortality is thankfully very low in the UK, mainly due to improvements in perinatal care (largely driven by midwives #washyourhands #RIPSemmelweis) and advances in vaccinations (more on this later) 3/n

as a second aside, progress made in reducing childhood mortality is now stagnating, probably as a result of underinvestment in children's services and growing socioeconomic inequality ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulati… 4/n

these sentiments are echoed by my clinical colleagues, who throughout the course of the research described in this thread consistently made their feelings known in post-talk feedback 5/n

so why bother? 6/n

for me, the strongest reason to invest in investigating the incredible complexity of the world around us is that we have no way of predicting of what will be useful for us in 50, 100 or 200 years time 7/n

take as an example a development which has helped to drag (some countries) out the Covid-19 pandemic: mRNA vaccines nejm.org/doi/full/10.10… 8/n

where do we start with the foundations for these? 9/n

the development of a stabilised RSV Fusion protein science.org/doi/10.1126/sc… which was the conceptual breakthrough for the development of Spike mRNA vaccine? (published 2013) @McLellan_Lab @BarneyGrahamMD 10/n

the development of stabilised mRNA pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16111635/ ? (published 2005) @kkariko 11/n

the discovery of messenger RNA sciencedirect.com/science/articl… ? (published 1961) 12/n

the realisation that nucleic acids could carry genetic information rupress.org/jem/article/79… ? (published 1944) 13/n

the discovery of nucleic acids sciencedirect.com/science/articl… ? (described 1869) 14/n

you see my point 15/n

the work described in our paper is based on 4 interesting studies published in 2011, 2012 & 2015

the first 2, both published in 2011, and looking at yeast, described an unusual pattern of mutations associated with retained ribonucleotides in DNA pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21700875/ 16/n

the first 2, both published in 2011, and looking at yeast, described an unusual pattern of mutations associated with retained ribonucleotides in DNA pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21700875/ 16/n

and related to topoisomerase 1 activity; researchers described an increase in short deletions at tandem repeats 17/n

the third paper, with the incomparable @MartinReijns as its first author sciencedirect.com/science/articl…, showed that every time a mammalian cell divides, an estimated 1,000,000 ribonucleotides are incorporated and then removed by an enzyme called RNase H2 18/n

the fourth paper is a beautiful study from Sparks and Burgers showing the mechanism by which topoisomerase 1 activity leads to short deletions by its action on retained ribonucleotides embopress.org/doi/full/10.15… 19/n

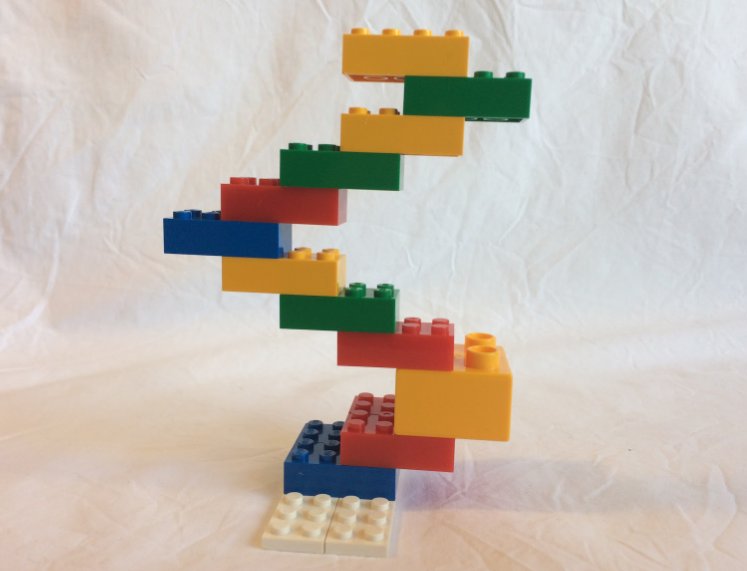

in living organisms, the main carriers of genetic information are DNA (LEGO) and RNA (DUPLO); they are similar but also fundamentally different 21/n

when new DNA is made, RNA is occasionally misincorporated: pieces of DUPLO end up in the LEGO.

If you try this at home, you'll see that they can fit together, but not particularly well 22/n

If you try this at home, you'll see that they can fit together, but not particularly well 22/n

these can be resolved by another enzyme called topoisomerase 1, although this is a messy process and can lead to permanent changes in the order of the LEGO: mutations 25/n

our big question was whether the process that had been seen in yeast also takes place in human cells 26/n

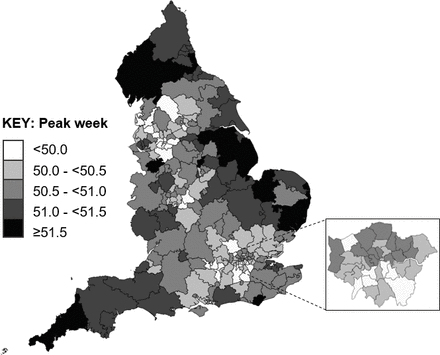

our work shows that it does, linking topoisomerase 1 activity to a mutational signature called ID4 27/n

in cancer cells and also in the germline, potentially explaining some of the harmful mutations that lead to human diseases, and the variation seen in human populations today 28/n

will anyone benefit directly from this work? 29/n

it does in fact potentially have implications for cancer therapy, as nicely articulated in a companion piece @NatureNV nature.com/articles/d4158… by Ludmil Alexandrov and @AmmalAbbasi 30/n

but more fundamentally, it overturns the assumed mechanism for these types of mutations, polymerase slippage, a view which has been held since the 1960s pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5237214/ 31/n

time will tell whether these findings will change how we do things in the future, but the fundamental point is this:

we can't predict which work will be impactful or which won't, and we shouldn't let this stop us exploring the world around us 32/n

we can't predict which work will be impactful or which won't, and we shouldn't let this stop us exploring the world around us 32/n

none of this work would have been possible without the insight and input of researchers across Edinburgh and the world

my co-authors @MartinReijns @JacksonMedapj @mst_paralogue @d_a_parry @DianaRSzwed & @Mdnicholson3 (+others not on Twitter) @EdinUni_IGC & @mrc_hgu 33/n

my co-authors @MartinReijns @JacksonMedapj @mst_paralogue @d_a_parry @DianaRSzwed & @Mdnicholson3 (+others not on Twitter) @EdinUni_IGC & @mrc_hgu 33/n

our collaborators across the UK and Europe:

@clpalles & @TatjanaStankov5 @unibirmingham @AnnaSchuh3 @UniofOxford

@KonradAden @kieluni

@FerranNadeu @idibaps 34/n

@clpalles & @TatjanaStankov5 @unibirmingham @AnnaSchuh3 @UniofOxford

@KonradAden @kieluni

@FerranNadeu @idibaps 34/n

in addition huge thanks to the ever reliable @BretherickA for computational expertise

@kudlalab whose door was always open for a chat

@EcatTrack & @wellcometrust for funding and support

@BoxtelLab for sharing sequence data

+many others too numerous to name 35/n

@kudlalab whose door was always open for a chat

@EcatTrack & @wellcometrust for funding and support

@BoxtelLab for sharing sequence data

+many others too numerous to name 35/n

really such a privilege and pleasure to be part of the scientific endeavour END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh