The rage & fear you feel after the Russian invasion are ancient parts of your mind preparing - like clockwork - for a world of conflict.

After 10 years of research in the lab & field, it is surreal to feel it unfold in my own mind

A 🧵 on what happens & with what effects (1/16)

After 10 years of research in the lab & field, it is surreal to feel it unfold in my own mind

A 🧵 on what happens & with what effects (1/16)

I lived during the Cold War but never felt its threat. Many Westerns have never experienced anything remotely like war.

But you are more than your experiences. Your mind was designed by natural selection and the genes you carry are adapted to a different world. (2/16)

But you are more than your experiences. Your mind was designed by natural selection and the genes you carry are adapted to a different world. (2/16)

That world included violent, group-based conflict. Scholars disagree on the details of the prehistory of war. But group conflict is universal, ancient & significant enough that it may have shaped our basic psychology (doi.org/10.1162/ISEC_a…) (3/16)

But the world of our ancestors was also a cooperative world (doi.org/10.1146/annure…). We are designed for both, for detecting when things shifted in one or the other direction & for using different social strategies depending on the context. (4/16)

Succes in a cooperative world depends on prestige = solving other people's problems. Succes in a world of violent conflict depends on dominance = fear, intimidation & aggression (doi.org/10.1037/a00303…) (5/16)

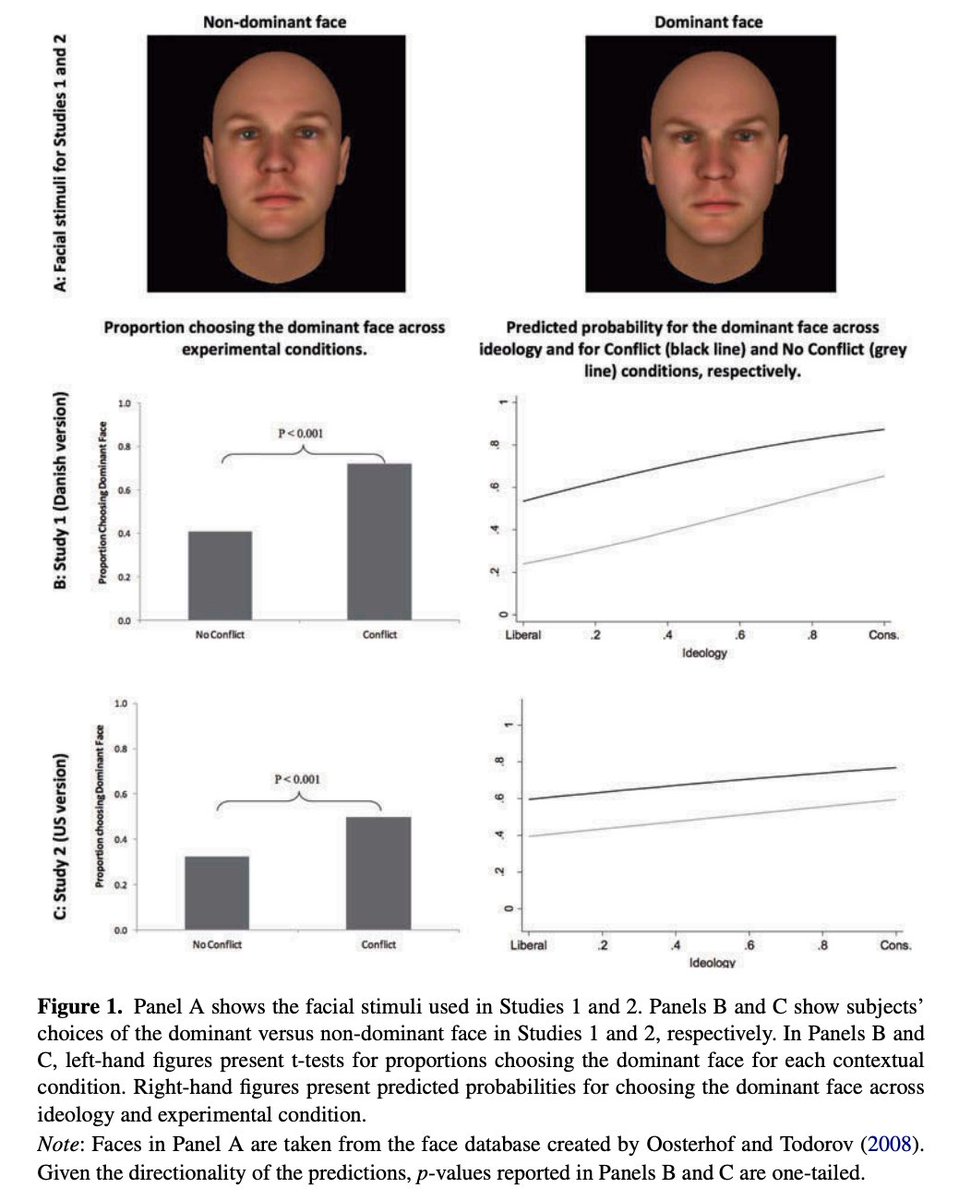

In our research, we find that shifts towards dominance happen with high speed in conflicts. Exposure to threat from other groups (but not natural threats) elicit immediate support for dominant leaders (doi.org/10.1111/pops.1…) (6/16)

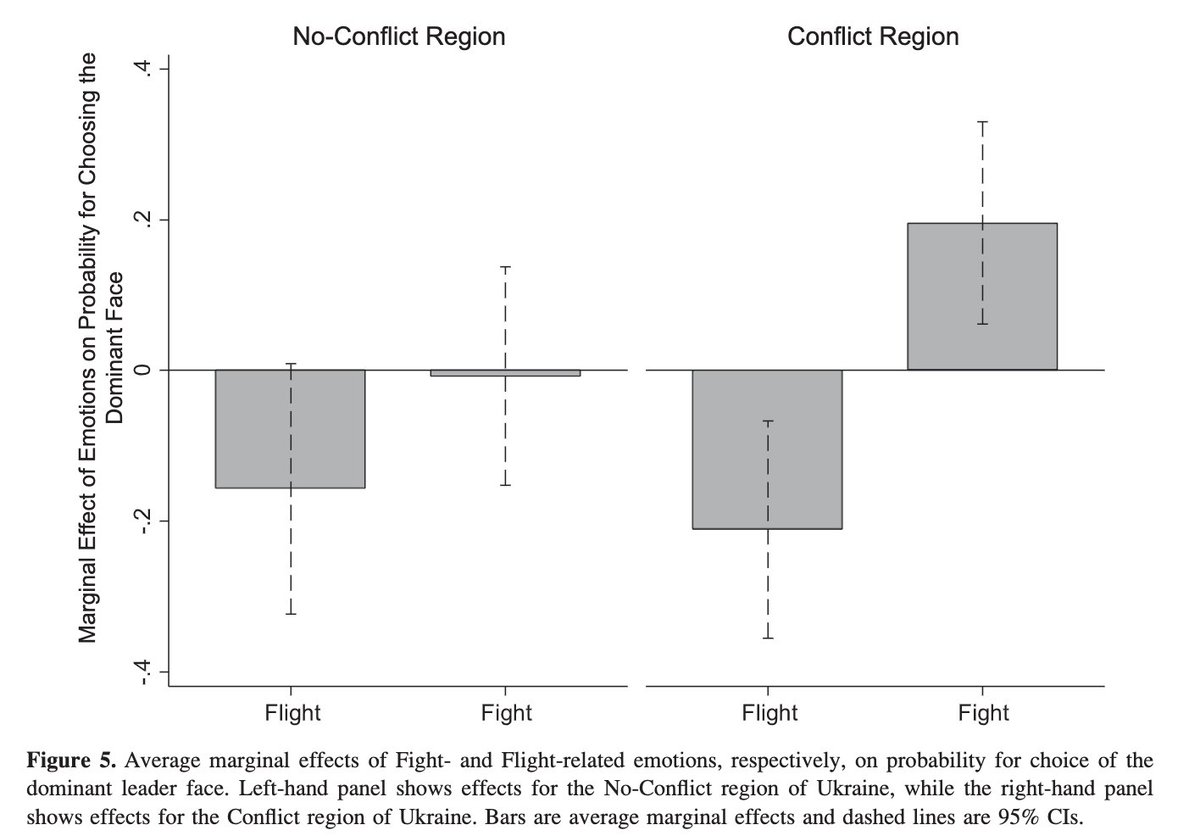

But not everyone feels the same. We studied this when Russia invaded Crimea in 2014. In the face of the invasion, feelings of anger increased support for dominant leaders among those in the affected regions. Feelings of fear decreased support (doi.org/10.1111/pops.1…) (7/16)

Emotions are coordination systems designed to refocus your entire cognitive architecture towards a specific task: They change what you attend to, how you assess costs & benefits associated with actions & prepares your body to execute those actions (psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-07…) (8/16)

Anger and fear both reflects acceptance of a world of dominance. Anger is the emotion of navigating that world by being dominant. Fear is the emotion of navigating the world of conflict through submission. Both can be necessary at different times. (9/16)

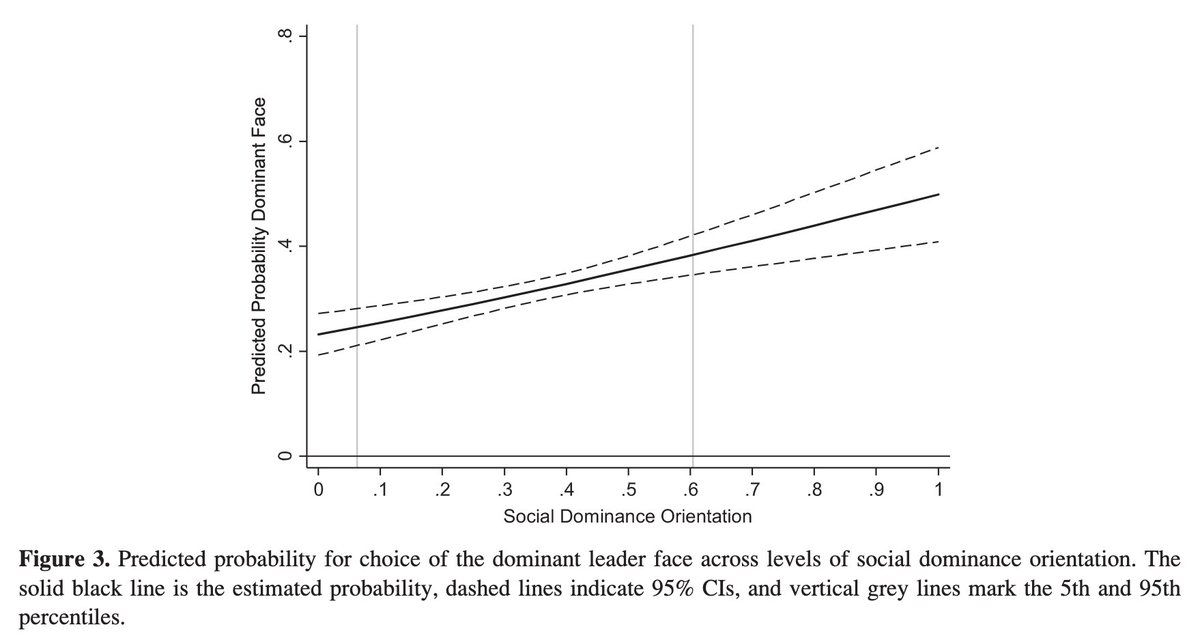

Everyone feels a mix of emotions. But why do some feel more anger than fear and vice versa? Personality is likely a key factor: Those having a personality already oriented to threats from other groups leads to greater support for dominance (doi.org/10.1111/pops.1…). (10/16)

As the rage of Putin's atrocities attune the minds of millions of citizens across the Western world to a world of dominance (and shift the focus away from prestige), it will have a number of psychological and political consequences. (11/16)

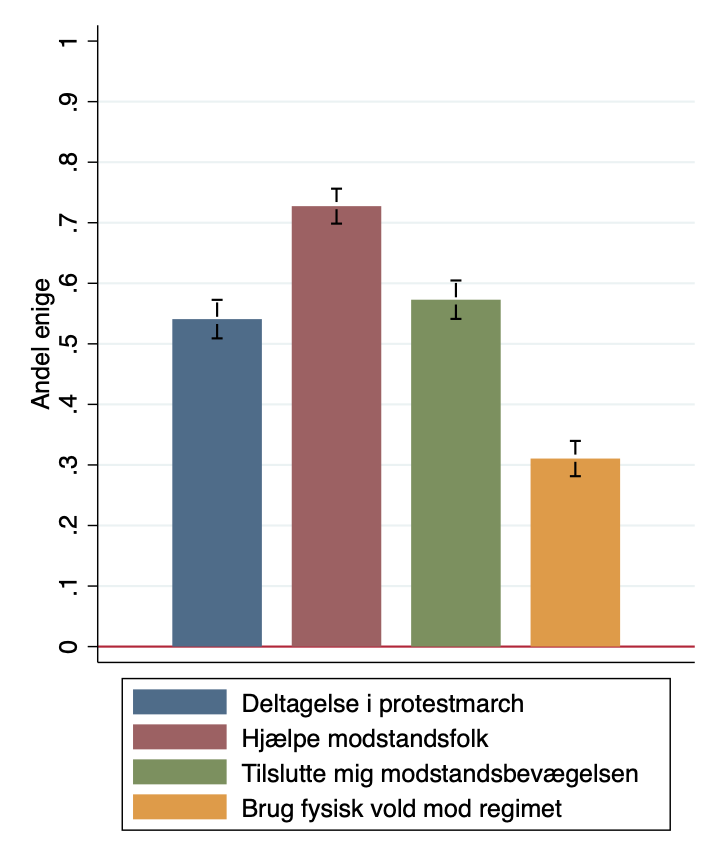

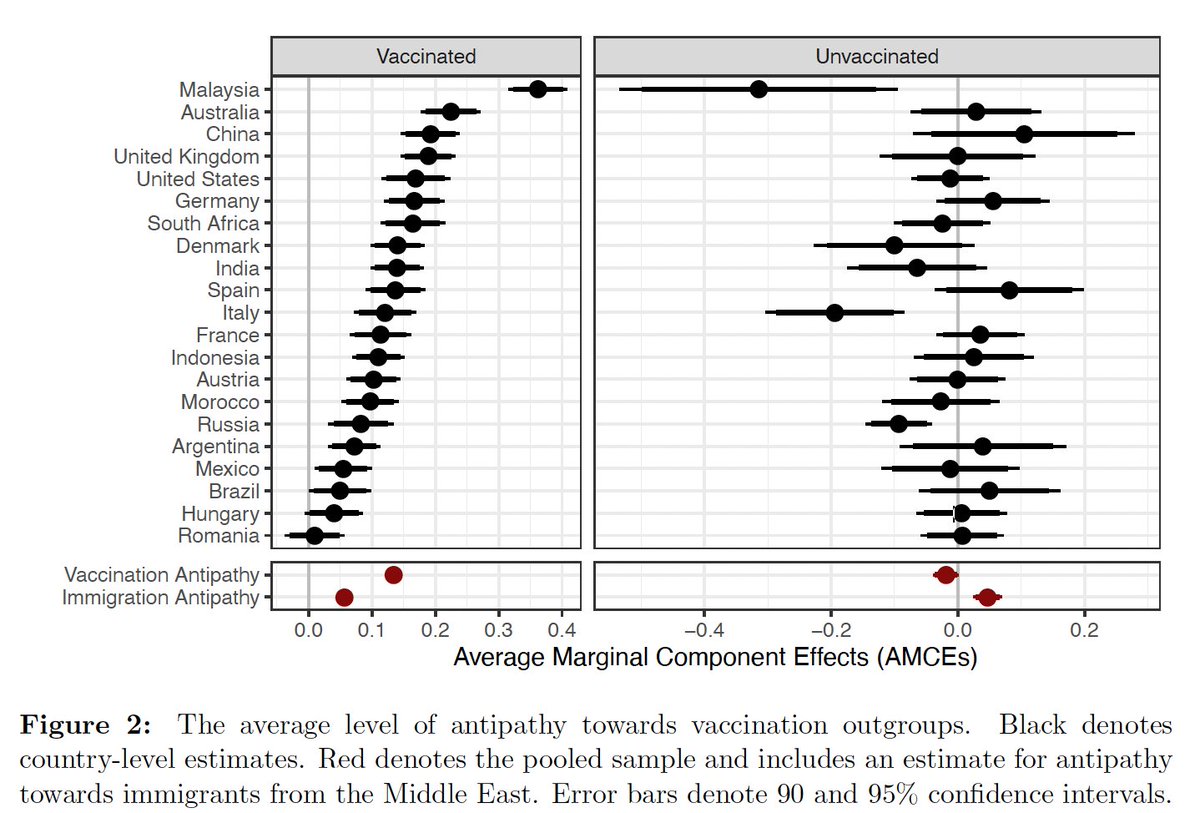

Support for violence, dominant leaders & the spread of misinformation about the enemy will increase ((doi.org/10.1111/pops.1… & psyarxiv.com/puqzs/). Those feeling fear will decrease support for aggression, opening a new political cleavage (doi.org/10.1037/a00248…). (12/16)

These effects involves altered perceptions. Risks associated with war will begin to look smaller (doi.org/10.1037/0022-3…). This is not a "cognitive bias" but a design feature of a mind shifting from navigating a prestige-based world to a dominance-based world. (13/16)

A week ago it would be unfathomable for many to support war preparations. Now leaders & citizens across the Western world hail the old Roman saying of "para bellum": if you want peace, prepare for war. Indeed, this is the doctrine of a world of dominance & I feel it too. (14/16)

So, if you have feelings you never had before & support policies you would never have supported before, it essentially reflects the activation of a deep-seated psychology designed for a world of dominance contests between groups. (15/16)

BUT: Your psychology was designed for a world of small-group aggression. Not a world of nukes. This mismatch means that your intuitions are not always optimal guides. Balancing emotions for group-aggression with cold reason is key over the next days and, possibly, years. (16/16)

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh