Been asked for data sources re my #suicideprevention talk at #RCPsychIC. Mainly @ONS & my research unit @NCISH_UK - link to our website.

Short 🧵 on our research findings.

sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/

Short 🧵 on our research findings.

sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/

First, important reminder that graphs & data represent real lives lost, families devastated.

Our national study of suicide in CYP, almost 600 deaths over 3 yrs, based on data from inquests & other official sources.

Shows rapid rate rise in late teens & important stresses such as bullying, suicide bereavement & exams.

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

Shows rapid rate rise in late teens & important stresses such as bullying, suicide bereavement & exams.

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

From same study, focus on online risk. 1/4 of CYP dying by suicide were known to have used internet in “suicide-related” way.

Public concern is on social media but more common was searching for info on methods. Need to tackle these dangerous sites.

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

Public concern is on social media but more common was searching for info on methods. Need to tackle these dangerous sites.

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

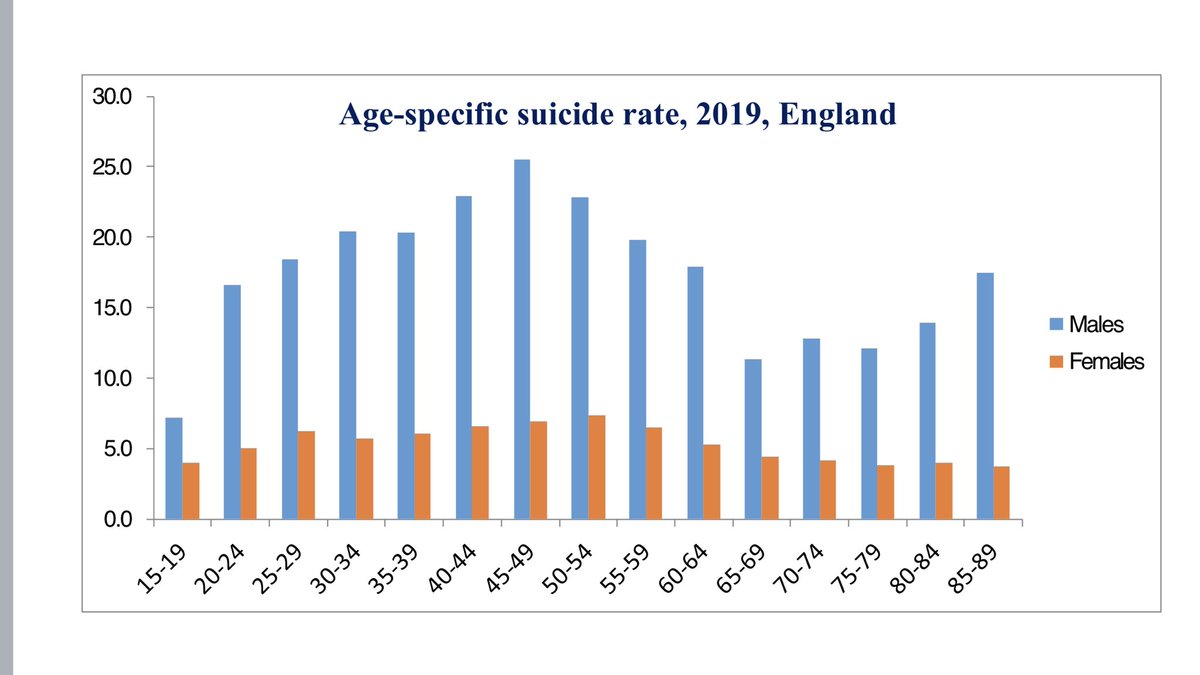

Our national study of suicide in middle-aged men. Highlights financial probs & alcohol. Our assumption that men don’t seek help is simplistic - 2/3 had contact with services in previous 3m, 1/3 in final week.

sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/reports/…

sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/reports/…

Our annual report for 2022. Around 1600 MH patients/yr die by suicide in UK. Data on suicides in & soon after IP care. Max risk is on day 3 post-discharge.

sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/

sites.manchester.ac.uk/ncish/

We tracked patient suicide rates against changes in MH services. Best evidence for prevention included safer wards, early follow up on discharge, crisis teams, outreach, incident review. Became our “10 ways to improve safety” message.

thelancet.com/journals/lanps…

thelancet.com/journals/lanps…

Study of suicide risk assessment tools. We found 156 in use nationally, many self-designed. Poor validity & prediction, should be replaced by more personalised model of care.

thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/…

thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/…

We tracked suicide in the early pandemic by “real time surveillance”- recording suspected suicides as they happened. Despite much concern & many claims, we found no rise.

Economic protections, social cohesion, stronger services & communities?

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Economic protections, social cohesion, stronger services & communities?

sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

Message of my talk at #RCPsychIC22:

Need to learn from positive evidence of pandemic but also pre-pandemic trends: CYP, ethnic minorities, domestic violence, gambling & online.

Suicide is preventable but pattern of risk is changing & we need to be constantly vigilant.

Need to learn from positive evidence of pandemic but also pre-pandemic trends: CYP, ethnic minorities, domestic violence, gambling & online.

Suicide is preventable but pattern of risk is changing & we need to be constantly vigilant.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh