Continuing with my series of threads for #Castlereagh200, looking at #ViscountCastlereagh's career through the lens of #MentalHealth. Let's turn to the second major area of risk for chronic stress in the workplace: emotional demand.

1/

CW: suicide, violence

#twitterstorians

1/

CW: suicide, violence

#twitterstorians

Specifically, I want to focus on a stressor that is important in politics: tension with the public. Research has shown that jobs where there is sustained tension with the public (e.g. public hostility) have higher levels of chronic stress, contributing to poor mental health.

2/

2/

It's well known that Castlereagh was an unpopular politician (esp. within radical and reformist movements), but what is particularly striking about the printed attacks on Castlereagh in satires and pamphlets, apart from their frequency, is their highly personalised nature.

3/

3/

Often, illustrations and texts perpetuated a dark image of the Castleregah as the government’s chief enforcer. Caricaturists regularly portrayed him holding a scourge, meant to reinforce the myth that he had been personally complicit in torture during the 1798 rebellion.

4/

4/

Perhaps most disturbing is the number of times, starting around 1820, that satires portrayed Castlereagh's violent death, by either execution or suicide, 2 years *before* he took his own life. Let's consider some examples...

5/

5/

In one of William Hone’s popular pamphlets, Castlereagh and other ministers are portrayed as farm birds. On the last page of the pamphlet, a woodcut shows all the birds hanged by the neck from a lamp post under a sign reading ‘JUSTICE TRIUMPHANT.’

6/

6/

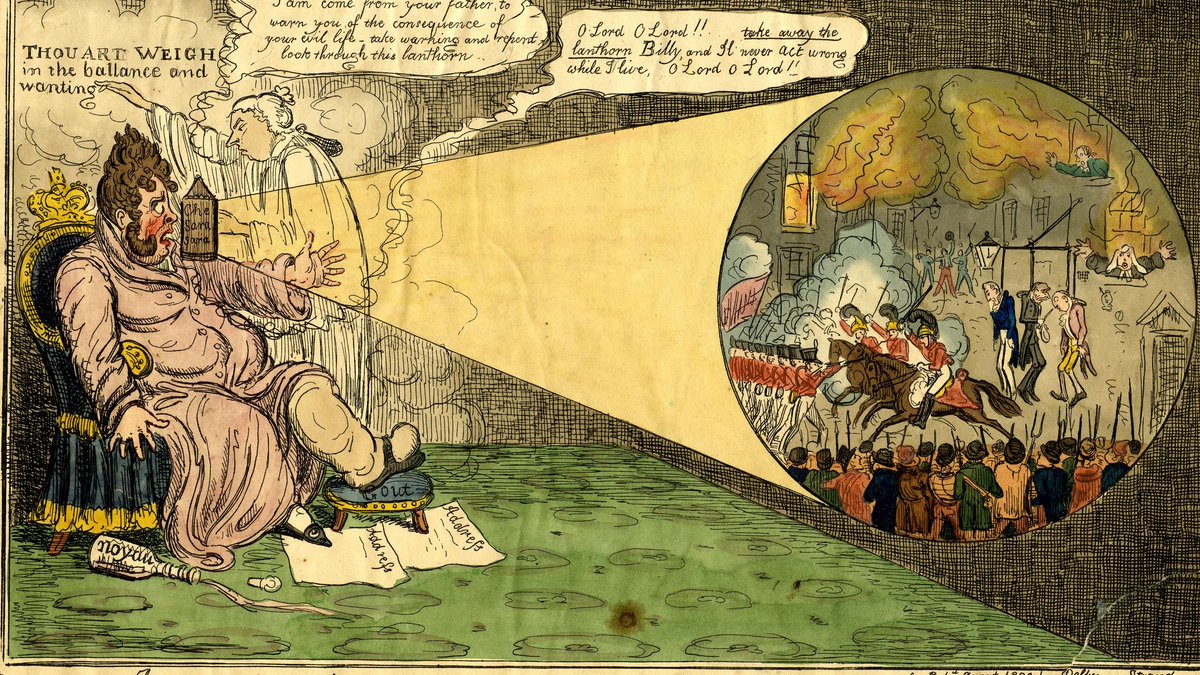

In the 1820 print below, a spirit shows the Prince Regent his future through a magic lantern--the people have risen up against the government, and Castlereagh, Sidmouth, and Liverpool are again shown hanged from a lamp post.

7/

7/

Another of Hone’s 1820 pamphlets shows Castlereagh sitting dejected and alone at the foot of a tree, with a noose hanging suggestively from the tree’s branch.

In the pamphlet 'The Queen in the Moon,' an image shows Castlereagh, Sidmouth, and Canning hanged from gallows.

8/

In the pamphlet 'The Queen in the Moon,' an image shows Castlereagh, Sidmouth, and Canning hanged from gallows.

8/

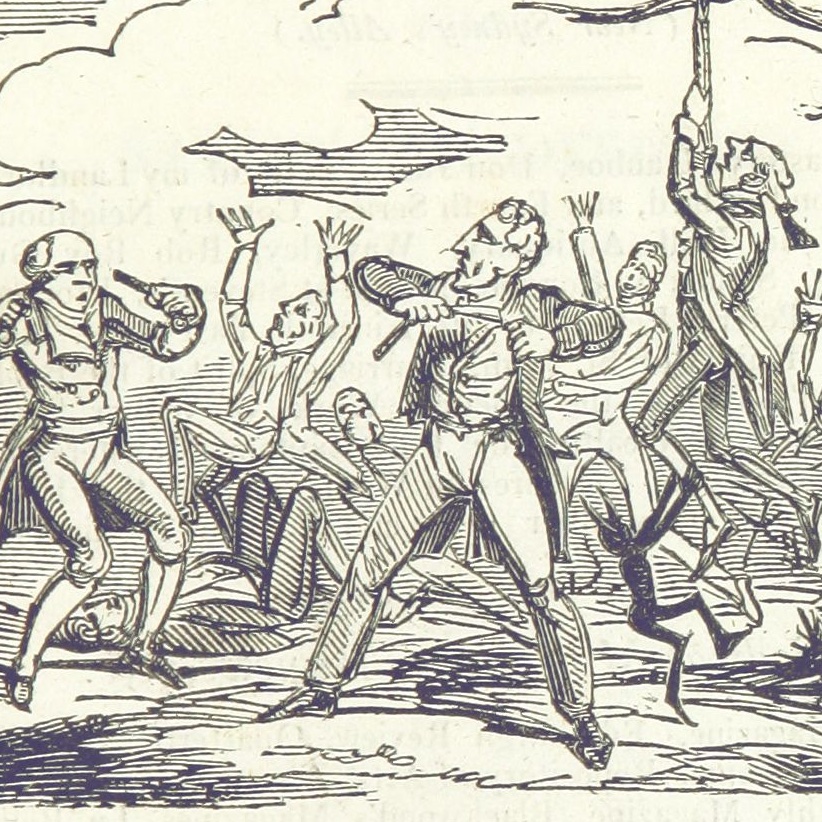

The final page of the same pamphlet contains an image that is particularly poignant, given Castlereagh’s method of suicide only 2 years later; it shows all the government ministers scrambling to end their lives and in the foreground is Castlereagh, about to cut his own throat.

9/

9/

In addition to satirical prints, Castlereagh’s character was frequently attacked in written works. In an 1816 issue of The Examiner, William Hazlitt referred to Castlereagh as a ‘good-natured man,' but he defined a 'good-natured man' as:

10/

10/

“utterly unfit for any situation or office in life that requires integrity, fortitude, or generosity”

“There is no villainy to which he will not lend a helping hand with great coolness and cordiality, for he sees only the pleasant and profitable side of things.”

11/

“There is no villainy to which he will not lend a helping hand with great coolness and cordiality, for he sees only the pleasant and profitable side of things.”

11/

Richard Carlile, in an 1820 issue of The Republican, referred to the Irish Rebellion as the first instance where Castlereagh showed his “native disposition":

12/

12/

"Your lordship could sit in your office and witness the rising and falling of the lash, hear the groans of the mangled, smile at the outrage of humanity, and pride yourself on having invented an improvement upon torture."

13/

13/

The key consideration here is the frequency with which the criticism of Castlereagh went beyond policy and became personal. On a regular basis, Castlereagh wasn't just portrayed as a bad politician, he was portrayed as a bad person--and one that deserved a violent end.

14/14

14/14

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh