Happy #MosasaurMonday!

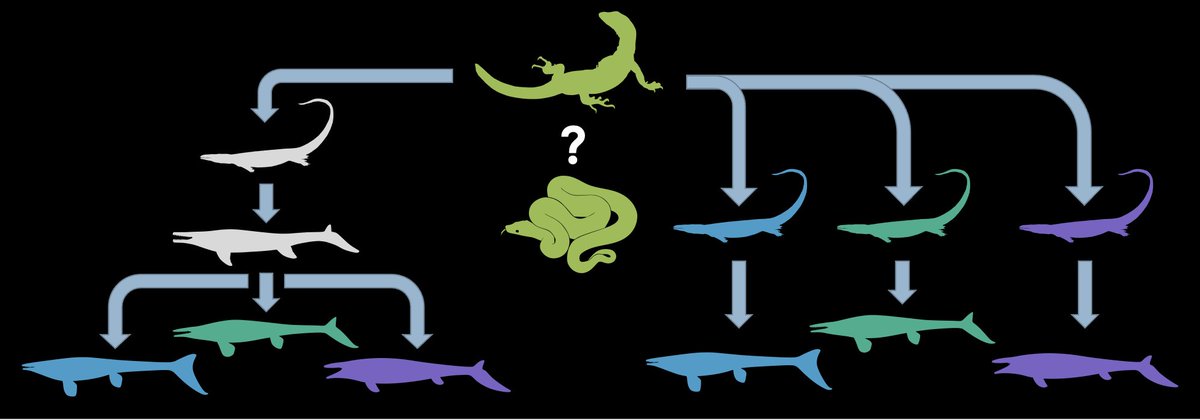

While I'm 'celebrating' by making final tweaks to the ND critter manuscript, it occurred to me that there's something very important we don't actually talk much about in paleo social media circles: how *do* you describe a new species, anyway?

Time for a 🧵!

While I'm 'celebrating' by making final tweaks to the ND critter manuscript, it occurred to me that there's something very important we don't actually talk much about in paleo social media circles: how *do* you describe a new species, anyway?

Time for a 🧵!

Perhaps unsurprisingly, properly identifying & diagnosing extinct species is incredibly tricky! For starters, because they are, necessarily, dead & gone, we cannot use many of the same species concepts we use for living animals (e.g., whether individuals interbreed)

🎨F. Matthews

🎨F. Matthews

For most fossil taxa, we aren't lucky enough to have the DNA nor soft tissue, & so we are left with 🦴the b o n e s🦴.

Not only that, but we are only left with the bones that *fossilize* AND *are collected*! Most fossils in collections aren't perfect skulls - most look like this

Not only that, but we are only left with the bones that *fossilize* AND *are collected*! Most fossils in collections aren't perfect skulls - most look like this

Not all new species come from newly dug-up fossils; sometimes, it just takes someone noticing that the anatomy of an individual is just a bit off, which happened recently: the new mosasaur Gnathomortis was described in 2020 from a fossil that was found in 1975!

🎨@Paleoartologist

🎨@Paleoartologist

Now, on to the meat of it: how do you tell whether a given individual is a new species? The answer is apomorphies! An apomorphy is an anatomical trait that is unique to a taxon. Any new taxon MUST have apomorphies - otherwise, it CANNOT be reliably & consistently identified!!

Apomorphies need to be anchored to a holotype - that is, a single specimen that bears the new name. For a 2nd specimen to be referred to a given species, it MUST have anatomical overlap with the holotype - same age/locality is NOT enough on its own...

..& on top of that, you have to be sure that all the parts of your holotype belong to one individual! Otherwise, you could create a chimera: a species diagnosed by a fictional combination of apomorphies resulting from the holotype material actually including two (or more) species

So, how do you figure out whether your holotype is actually a new thing? I.e., how do you determine whether the differences you've noticed are really apomorphies? Easy: a thorough comparison of your specimen to every other known taxon! Thankfully...

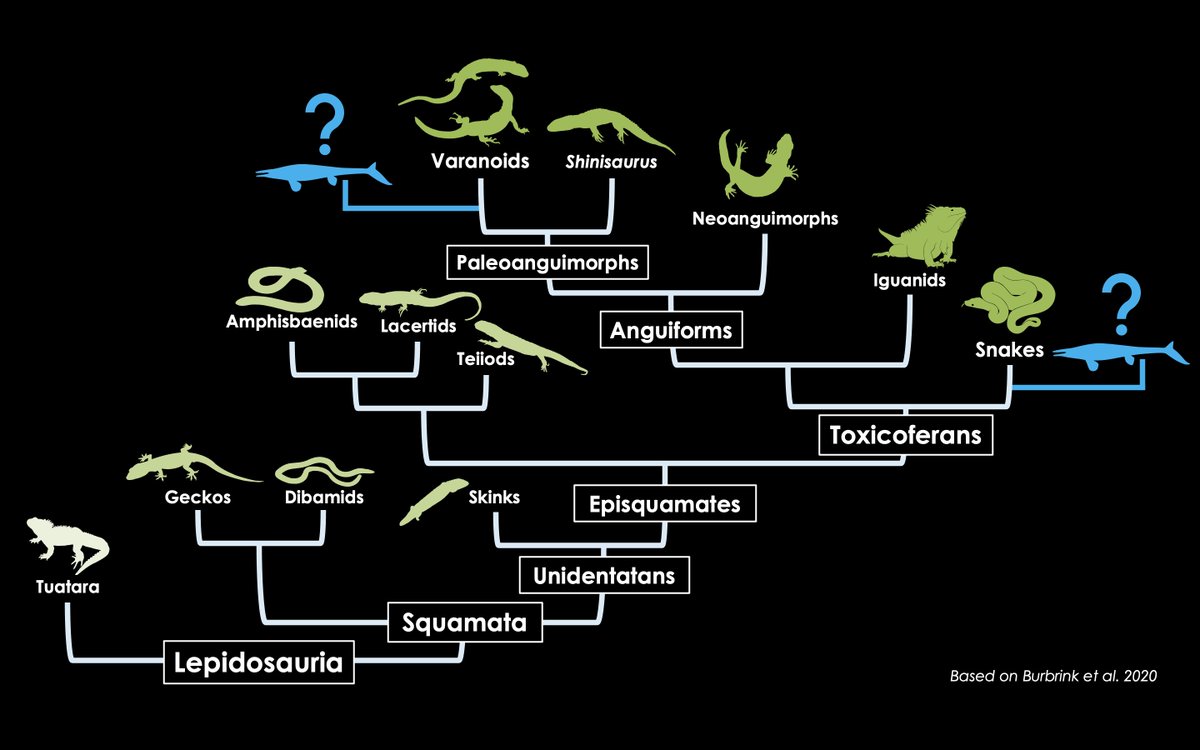

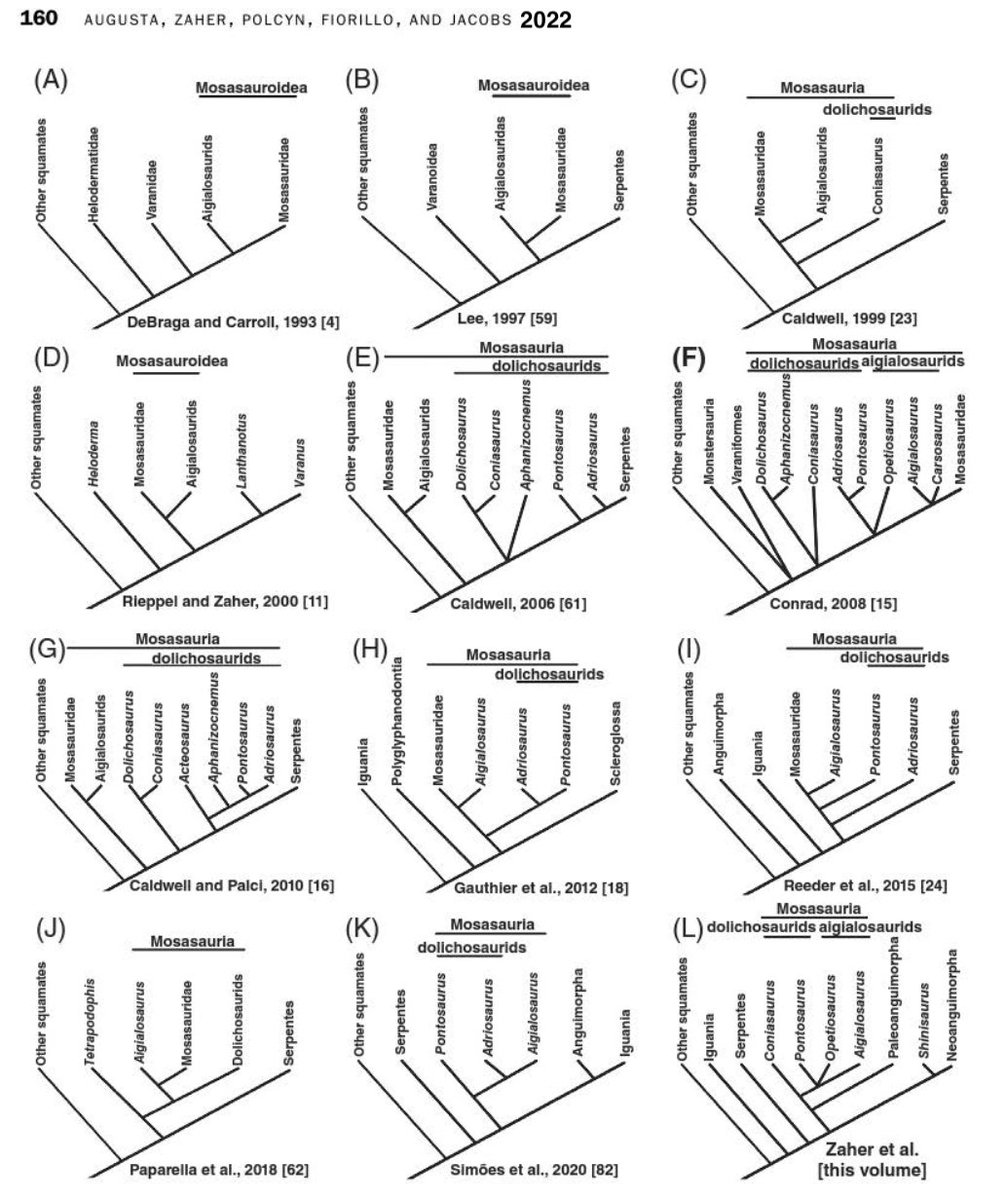

...you rarely need to compare your specimen to *every* known species, because higher clades (genera, families, etc) have apomorphies, too! Using these traits, you can narrow down your pool of reference species (e.g., ND critter has several unambiguous mosasaurine apomorphies)

Again, a *thorough* literature review & comparison of your holotype with known species, plus an understanding of existing clade apomorphies, is key to avoiding your new taxon becoming a nomen dubium (i.e., future work designates your holotype undiagnostic & the name is abandoned)

Once you establish that your holotype is (1) diagnostic & (2) one individual, congrats! You're ready to do some osteological description & score your critter into a phylogenetic matrix to find its relatives!

But...what if your new thing turns out to not be new after all?

But...what if your new thing turns out to not be new after all?

In short, it happens & that's okay! In the long run, it's much better to be conservative with taxonomy, as it's much easier to erect new species later on than sink them (& clean up the resulting identity mess).

That's all for now; as always, feel free to reach out with questions!

That's all for now; as always, feel free to reach out with questions!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh