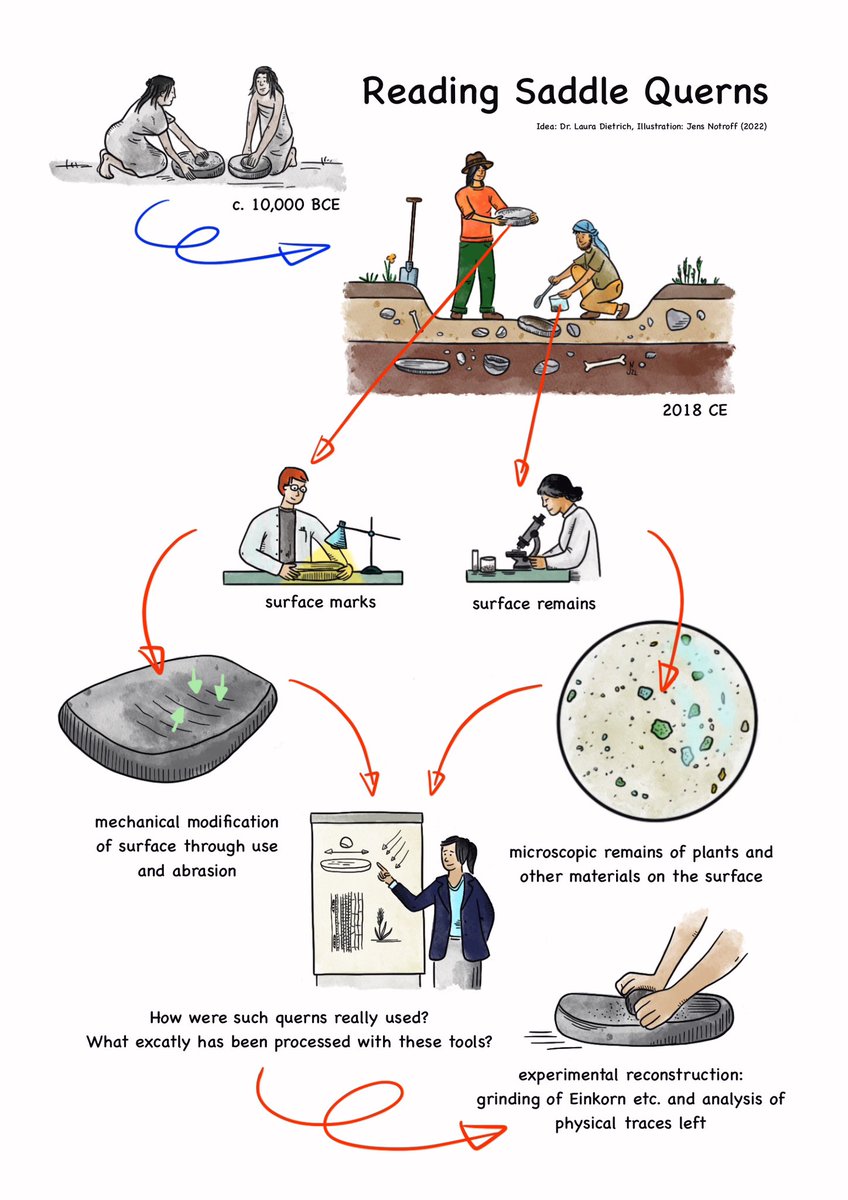

How ongoing research is increasing the available corpus (and our understanding) of Pre-Pottery #Neolithic #iconography.

Just a little #archaeology 🧵 on why this is really fascinating. 😉

@DrKillgrove reporting on new finds from #Sayburc in SE Turkey for @LiveScience:

Just a little #archaeology 🧵 on why this is really fascinating. 😉

@DrKillgrove reporting on new finds from #Sayburc in SE Turkey for @LiveScience:

https://twitter.com/LiveScience/status/1600641994539278336

Original report ("The #Sayburç reliefs: a narrative scene from the #Neolithic") by E. Özdoğan in @AntiquityJ 96(390), 2022:

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

cambridge.org/core/journals/…

Of course, the phallus-flashing guy gets all the headlines.

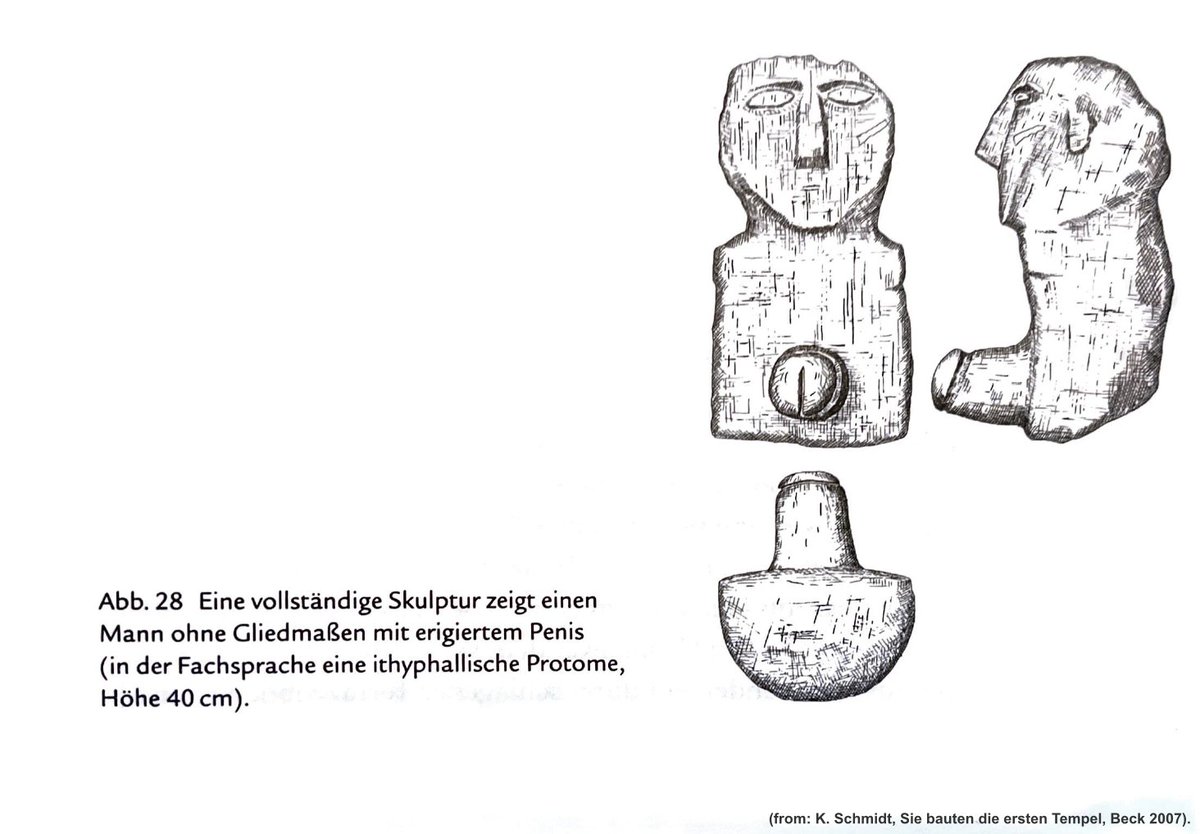

Well, it *is* quite a picturesque scene - one fitting #Neolithic iconographic conventions in the region & an apparently strong focus on male depictions (here's e.g. a comparable image from contemporary #GobekliTepe).

Well, it *is* quite a picturesque scene - one fitting #Neolithic iconographic conventions in the region & an apparently strong focus on male depictions (here's e.g. a comparable image from contemporary #GobekliTepe).

The #Sayburc image finds further parallels in the region's archaeological record:

The Urfa-Yeni Mahalle sculpture (a.k.a. #UrfaMan) for instance seems to wear similar clothing or a "collar" of sorts. And the cavity in his crotch area could well have fitted a separate phallus.

The Urfa-Yeni Mahalle sculpture (a.k.a. #UrfaMan) for instance seems to wear similar clothing or a "collar" of sorts. And the cavity in his crotch area could well have fitted a separate phallus.

Interesting's also the combination of #Sayburc man & those #leopards by his sides.

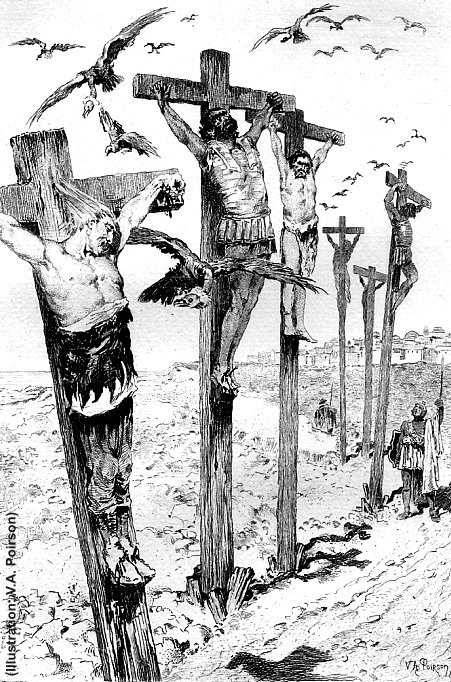

With bared teeth they seem to evoke danger. Such juxtaposition of virility & threat however finds parallels e.g. in the headless phallus-guy on #GobekliTepe's Pillar 43:

dainst.blog/the-tepe-teleg…

With bared teeth they seem to evoke danger. Such juxtaposition of virility & threat however finds parallels e.g. in the headless phallus-guy on #GobekliTepe's Pillar 43:

dainst.blog/the-tepe-teleg…

By the way: For these #leopards themselves we do also find clear analogies within the region's and period's #iconography. Namely, again, at #GobekliTepe.

(And the wonderful fur pattern here at #Sayburc also convince me to maybe finally give up our earlier #lion interpretation.)

(And the wonderful fur pattern here at #Sayburc also convince me to maybe finally give up our earlier #lion interpretation.)

Interesting sidenote: Of the #Sayburc #leopards one is also clearly denoted as male individual, the other (intentionally?) not.

The strong notion of danger and threat emanating from these feline predators - snarling, teeth bared, apparently leaping - however remains ...

The strong notion of danger and threat emanating from these feline predators - snarling, teeth bared, apparently leaping - however remains ...

Yet while Phallus-Guy™ gets all the press, that other scene also reported from #Sayburc is equally fascinating - offering additional insight into the world, and worldview, of those #Neolithic #hunters in SE #Anatolia.

Again, the #Sayburc #aurochs absolutely corresponds to what we'd expect considering the known #Neolithic iconographic programme:

The animal's depicted in sideview, but the head is turned, seen from the front, emphasising the horns as if attacking (again signalling danger).

The animal's depicted in sideview, but the head is turned, seen from the front, emphasising the horns as if attacking (again signalling danger).

This mode of depicting #aurochs heads even has become so specific that it’s been turned into what almost could be considered kind of a #Neolithic #meme:

The #bucranium substituting the whole animal and, emphasising the horns, arguably its most dangerous and impressive element.

The #bucranium substituting the whole animal and, emphasising the horns, arguably its most dangerous and impressive element.

But again it is this combination of powerful animal (here an #aurochs, able to put up a fight) and human which makes the whole scene so interesting - and extraordinarily fascinating.

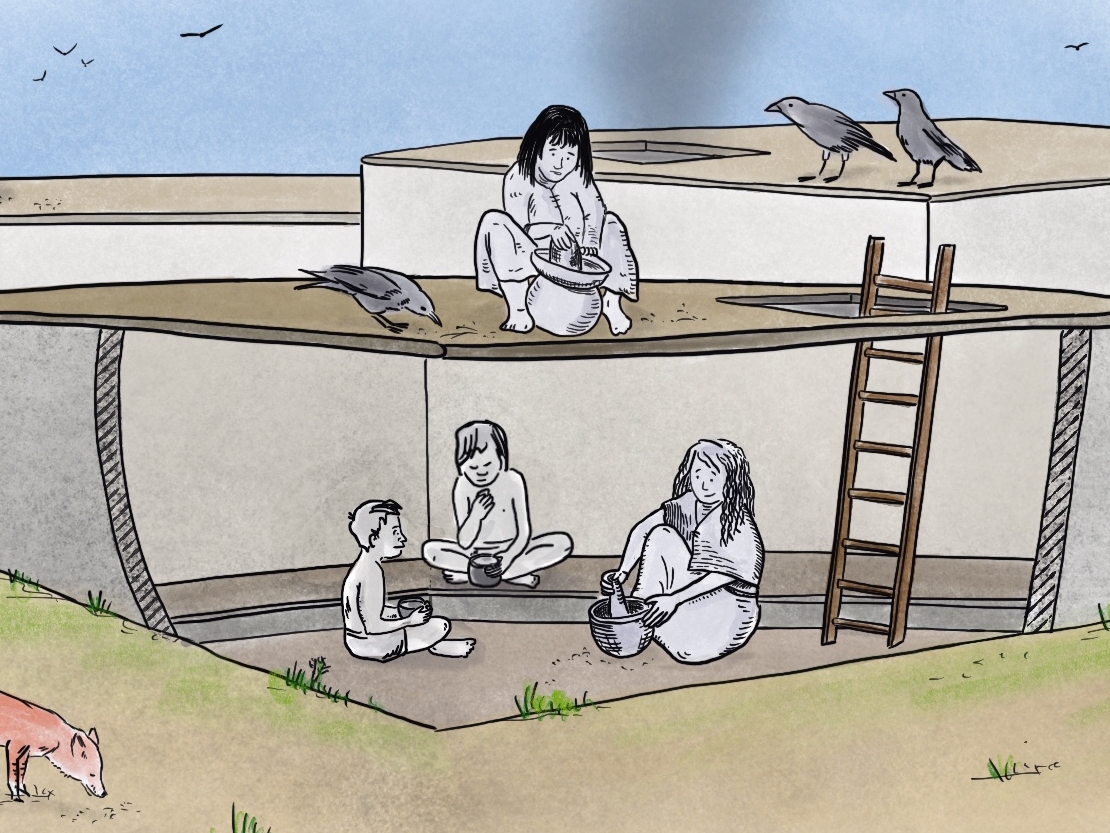

Somehow reminding of that famous (but a bit later) mural from #Neolithic #CatalHöyük ...

Somehow reminding of that famous (but a bit later) mural from #Neolithic #CatalHöyük ...

With the difference that in #CatalHöyük a group of people is depicted w/ an apparently *slain* #aurochs.

Its characteristic features (note the head: not any longer presenting horns (and danger), legs bend, tongue out) also known from #GobekliTepe's P66:

dainst.blog/the-tepe-teleg…

Its characteristic features (note the head: not any longer presenting horns (and danger), legs bend, tongue out) also known from #GobekliTepe's P66:

dainst.blog/the-tepe-teleg…

But at #Sayburc we see a still living animal, a still dangerous #aurochs (just imagine such an 1,600 pound heavy beast accelerating towards you 😱).

At #Sayburc we see a confrontation.

At #Sayburc we see a confrontation.

But what is this guy doing there? Messing around with an #aurochs?! 🤘🐮

Is this a hunting scene? What is it he's got in his hand there then? A #bow?

Is this a hunting scene? What is it he's got in his hand there then? A #bow?

From, yet again, another quite special find at #GobekliTepe (a bone with the still embedded tip of a #projectile point), we know that bow and #arrow certainly played a role in #Neolithic #aurochs hunting.

dainst.blog/the-tepe-teleg…

dainst.blog/the-tepe-teleg…

The oldest yet known physical examples of early hunting #bows actually date as far back as #Mesolithic Denmark, where at #Holmegaard the remains of five such bows, dating to c. 7000 BC, have been found:

en.natmus.dk/historical-kno…

en.natmus.dk/historical-kno…

Admittedly, it's a bit challenging to really recognise a bow here in this #Sayburc scene. So, could it be something else then?

This offers a great chance to think about other possible #hunting tools and weapons which have played a role in #Neoltihic hunting, #aurochs and beyond.

This offers a great chance to think about other possible #hunting tools and weapons which have played a role in #Neoltihic hunting, #aurochs and beyond.

From SW #Libya there are more & in this context particularly interesting hunting depictions known:

Here's a scene showing an #aurochs bow-hunt complemented by use of so-called #Fangsteine: rocks, which, once a fleeing animal's been entangled, helped tiring & slowing it down.

Here's a scene showing an #aurochs bow-hunt complemented by use of so-called #Fangsteine: rocks, which, once a fleeing animal's been entangled, helped tiring & slowing it down.

Additionally a possible use of similar throwing weapons not unlike #bolas has been discussed as well.

Finally, and this convinces me that we might read at least the left part of this #Sayburc depiction as #hunting scene, there are these interesting things called #ThrowingSticks.

With quite similar depictions again coming from #Catalhöyük.

revedeboomerang.free.fr/Master%20thesi…

With quite similar depictions again coming from #Catalhöyük.

revedeboomerang.free.fr/Master%20thesi…

In conclusion I'd like to mirror my statement from the article above, that I'm really excited to see how this ongoing archaeological research in the #Urfa region is more and more adding to our understanding of the world these #Neolithic hunters inhabited - and imagined.

tl;dr: With each new discovery archaeological research is adding new information to our image of past people's lives and world, pushing the limits of our knowledge about our own history.

Archaeology really is exciting even without bothering a lost Atlantean master race.

Archaeology really is exciting even without bothering a lost Atlantean master race.

PS: Dear colleague Bernd Müller-Neuhof also commented on the latest #Sayburc finds in @bannelia's @NewsfromScience article - and he too has some interesting thoughts to add:

science.org/content/articl…

science.org/content/articl…

Bernd knows what he's talking about here - he's also the author of that (related) "gestures typology" shared earlier today:

https://twitter.com/jens2go/status/1601158965999509504?s=20&t=q8mW71opzkR0ceANswSr1A

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh