Which Lord Londonderry is portrayed in this caricature/portrait by Richard Dighton?

A somewhat confusing🧵

#twitterstorians #19thC #portraiture

Image: Richard Dighton, @britishmuseum (BM), 1852,1116.559

A somewhat confusing🧵

#twitterstorians #19thC #portraiture

Image: Richard Dighton, @britishmuseum (BM), 1852,1116.559

Between roughly 1818-1828, Richard Dighton did a series of profile portraits of men in Regency London's high society. Most were etchings, and the BM has digitized many prints held in its collection--they are worth your time if you're interested in Regency society, style, and art.

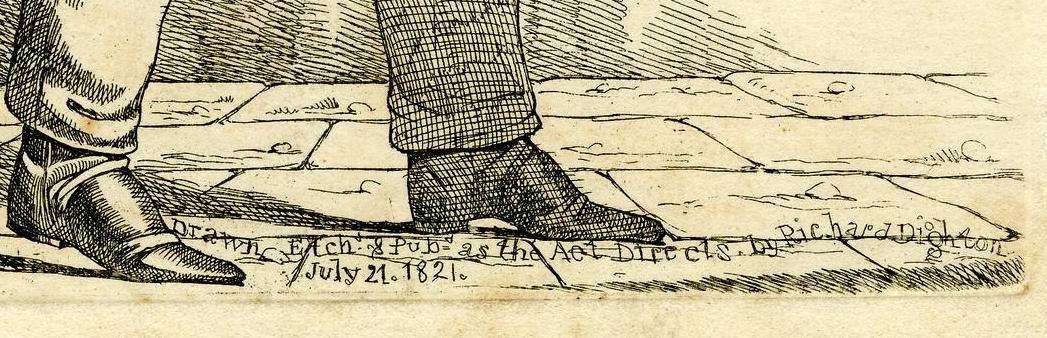

The earlier prints of this particular portrait, published individually by Dighton himself, are clearly dated to July 1821. Copies show up in the collections of the @britishmuseum, @NPGLondon, and @RCT.

(details shown here are from prints in the BM and RCT collections)

(details shown here are from prints in the BM and RCT collections)

Here's where things get confusing. Around 1824/5, Dighton likely sold the plates for a large number of these portraits to Thomas McLean, who re-printed them in 2 grouped collections, adding text indicating the subjects. This etching was titled 'A View of Londonderry.' (Image: BM)

When McLean re-printed the Dighton portraits in 1825, Charles Vane-Stewart was the 3rd Marquess of Londonderry. Charles was, of course, the younger half-brother of Robert Stewart, known popularly as #ViscountCastlereagh, who had died in August 1822.

This connection between McLean's re-printing of the portraits in 1825 and the fact that Charles was the Marquess of Londonderry at that time led to the identification of the subject of the Dighton portrait as Charles, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry.

Both Henry Hake's 1926 catalogue of Dighton caricatures and Dorothy George's 1952 catalogue of satirical prints in the BM collection identify the Dighton portrait with Charles, and Hake's and George's works set the tone for the BM's own collection records.

However, if we return to the original date of Dighton's portrait, July 1821 (which both Hake and George accept), the story isn't that simple. Between April 1821 and his death in August 1822, Robert Stewart (formerly Viscount Castlereagh) was the 2nd Marquess of Londonderry.

In fact, some prints of Dighton's portrait are titled 'A Late Foreign Secretary' in clear reference to Robert who had died in 1822 while he was Foreign Secretary. The print below is in the @NPGLondon collection (NPG D20569) and includes this title.

It gets more interesting when we consider that Dighton based these profile portraits on his observation of the subjects as they walked the streets of London--posture, gait, attitude, clothing, etc.

Here's the thing: Charles wasn't in London in July 1821.

Here's the thing: Charles wasn't in London in July 1821.

He was still in Vienna as the British Ambassador, a role he had held since 1814. Charles was in London briefly in Fall 1820 and returned in August 1821 for an extended visit (see @WhigDuke's excellent book 'War and Diplomacy'). But he was in Vienna in Spring/early Summer 1821.

Robert, on the other hand, was definitely in London in July 1821--as a senior cabinet minister he attended George IV's coronation on July 19. So, arguably, Robert was a more present subject for Dighton in London through Spring and early Summer 1821. Not conclusive, but important.

We can also compare the face in the Dighton print to two portraits done at roughly the same time presenting reliable likenesses of each Londonderry: Chantrey's 1821 bust of Robert (@YaleBritishArt) and Lawrence's 1818/19 portrait of Charles (print shown here in BM collection).

I wish I could offer you a conclusive answer, #twitterstorians, but this is one where the jury is still out.

What do you think?

Which Lord Londonderry was Dighton portraying?

What do you think?

Which Lord Londonderry was Dighton portraying?

@threadreaderapp unroll please

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh