A few months ago, I was googling STEM programs in prisons, and came across an ad, posted on eBay of all places. “Could there be a future in computer programming for prisoners?” #higheredinprison #edtech #stem @STEM_OPS @Prof_Andrisse

But it wasn’t from The Last Mile or Slack's Next Chapter, which are both nonprofits working in this space now. It was an IBM ad from 1970 in Scientific American. @TLM @IBM @sciam @SlackHQ bit.ly/3KbocNQ

I had no idea that computer programming was offered in prisons 50 years ago. As I dug a little bit into the archives of @JSTOR’s American Prison Newspaper Archives, I discovered this was happening all across the country. Via La Roca, AZ State Prison, 1974. bit.ly/3Yy5CDT

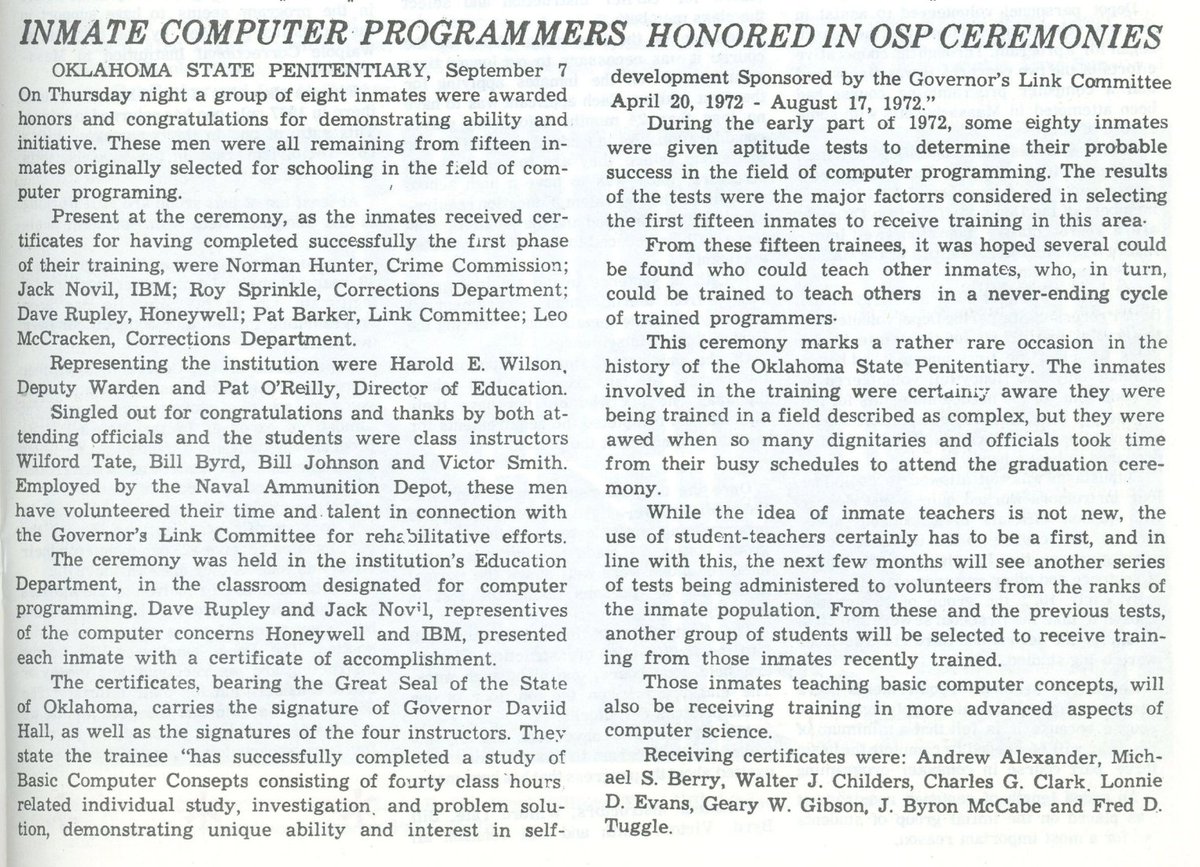

Including at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, from The Eye Opener, 1972, via @JSTOR. @morgangodvin jstor.org/stable/communi…

A 1967 story in @nytimes described a $1,200 computer course offered to incarcerated men for free. “The cells may be narrow, but the intellectual horizons are growing wider at Sing Sing,” McCandlish Phillips wrote. nyti.ms/3YVGJ4P

And most of this was done without access to a computer. “Since the convict programmers do not have direct access to a computer, all programs that they write are run through the ‘blackboard’ computer before they are given to the state agencies,” according to @Computerworld.

But that @IBM program in AZ? By 1978, it had been shut down by a new warden who didn’t understand it, as one man put it. “Under the guise of his security program, he put a stifle to the various programs around here.” From La Roca, AZ State Prison. bit.ly/3YPXxKk

What struck me the most about all of these historical examples was that the conversations we are having are exactly the same. We know that people are less likely to return to prison if they have marketable skills that lead to jobs in high-demand fields with livable wages.

They also raises questions about the the prison-industrial complex, with the state saving millions of dollars in contracts between corrections and other state agencies w/ the programmers making pennies an hour, but we didn't have the space to get into it in this particular piece.

In Connecticut, a man trained as programmer made the equivalent of $77K working at an insurance company after he got out. Via @JSTOR. The Weekly Scene, 1977, jstor.org/stable/pdf/com…

(A side note: prison wages haven’t changed much since 1975 either. That man in Connecticut earned $3 a day programming in prison — that’s still more than some prison jobs pay today). @PrisonPolicy

Today, the certification earned in a pilot program from Amazon Web Services at the DC Jail can bring in around $90k for an entry level position. @APDS_For_Good @awscloud aboutamazon.com/news/aws/this-…

While there are some innovative and interesting tech training programs in prisons out there right now, like at the DC Jail with @APDS_For_Good, the pockets of innovation are small. And we’re still asking the same questions, 50 years later. #edtech

Read more about this in my latest #CollegeInside newsletter for @opencampusmedia #higheredinprison #stem opencampusmedia.org/2023/02/15/the…

And #edtech will continue to be an important conversation as #PellGrants make #highered in prison more widely available, starting later this year. Sign up for my #CollegeInside newsletter for my ongoing coverage: opencampusmedia.org/category/newsl…

Please unroll @threadreaderapp

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh