If only preachers had stopped there.

-not sure why Christian clergy feels comfortable making "factual" statements in textbooks about how 2nd Temple Judaism worked without citing sources

-whenever Christians start talking about ritual purity, it's bad

-sigh

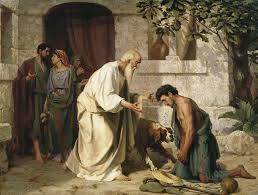

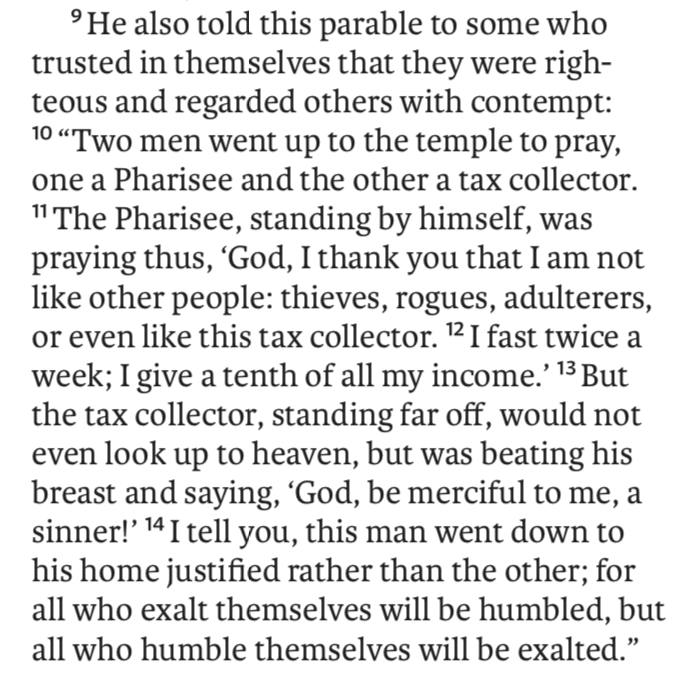

The moment you JUDGE the Pharisee, you BECOME the Pharisee.

If the point is to *choose* one of these men as "right," the only way to win is not to play.

Pharisees were the party of the people, decentralizing worship from the nobility- and Roman-controlled Temple into synagogues.

Far from being rigid legalists, they were engaged in trying to make the law *livable* and humane.

This is, to use a very treyf metaphor, complete hogwash.

For the tax collector to be *in the Temple at all* he has to be ritually pure.

The Pharisee reflects on the good he's done (which, incidentally, goes above and beyond the requirements), and expresses gratitude for not being like less virtuous people.

That's it.

And to understand that last, we have to talk about Sodom.

But the thing is, Abraham is making an incorrect assumption in that argument.

He's arguing that the merit of the innocent should protect the guilty.

What's that actually MEAN?

-Is the tax collector going to, y'know, STOP being a tax collector?

-Is it wrong to give thanks you're not in a position where you're tempted to behave harmfully? ("there but for the grace of God" prayers?)

-What's the Pharisee's responsibility to the tax collector?

-Is EITHER of these men "justified"?

Sub in "ICE agent" for "tax collector." Or, I dunno, who's not quite the 1% but eager to help them serf-ify the rest of us? A Wall Street bro? A pharma bro?

And can any of us be right with the universe alongside those people?

The point is: this story is full of questions. The answers are on us. Even on the most surface level, it's a Catch-22. Under that, it asks questions that are hard to face.

Fin. For now. Have more thoughts on this one, and thoughts on a bunch more, but not tonight.

And this very much comes down to how the reader interprets it. You can read it as contempt. You can also read it as understanding.

Is the tax collector going to change? If not, if he goes right on doing what he was doing, then what was this prayer for?

(I mean, from a Jewish perspective, praying for forgiveness for a sin you fully intend to keep committing is... kind of absurd.)

We ARE our brothers' keepers.

So here they both are in the Temple, the place one comes to formalize one's repentance, and this isn't a case where it's two strangers praying quietly and privately.

The question about the Pharisee is what does HE do next in regard to the tax collector? Does he say nothing?

What does each man do next?

What would WE do next in each of their positions? What SHOULD each do?

What would we do?

But I guess when you're a pastor you get to just... make up things about Judaism?

The problem is, this etymology is anything but certain.

The Zealots were the party of GET THEM OUT *NOW*.

That's not how this works.

Holiness, goodness, and purity are all *separate spectrums*, *separate systems* here.

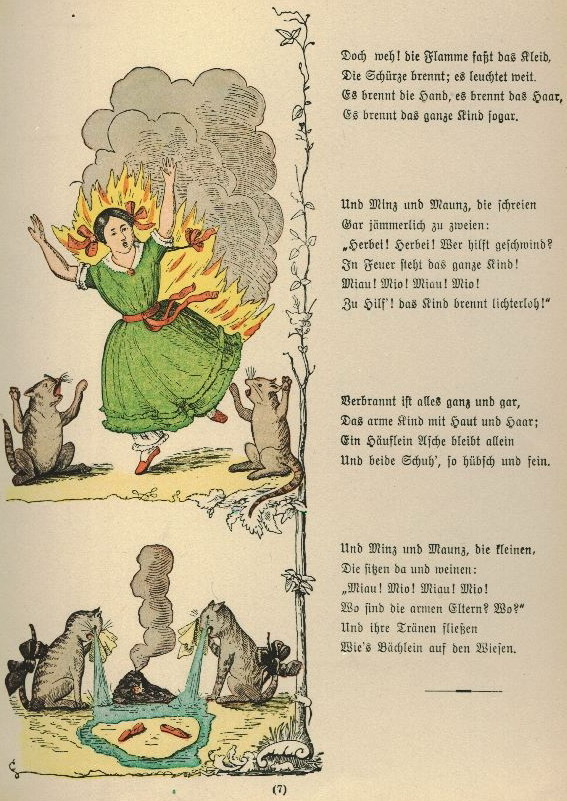

Impurity isn't about evil. It's about *intensity.* Things touching on moving into life or out of it, that partake of the numinous.

Ritual impurity wasn't a moral failing. Most Jews were ritually impure most of the time. You *have* to be to do important things like have kids and care for people. It's not a bad thing.

The only difference was that Jews sometimes made themselves ritually pure, which Gentiles didn't.

By definition, someone who never shaves is going to always be in a state of hairiness, but that doesn't mean they're inherently hairier than someone who shaves

So reading horror at ritual impurity, or the idea that Jews saw Gentiles as inherently unclean, into the parables is... um, a lot of projection.