In January -- corona volente -- I will be joining @the_IAS in Princeton for half a year. I'm very excited to join the people there.

While there I will be looking at the reading tradition of a specific group of manuscripts in the B.II style.

ias.edu/scholars/marij…

While there I will be looking at the reading tradition of a specific group of manuscripts in the B.II style.

ias.edu/scholars/marij…

The B.II style is one of the classical Kufic styles, frequently used in a somewhat miniature hand on small folios (usually around 15x21cm) with about 16 lines to the page. The dated copies that we have generally date from the 3rd century AH.

They have striking commonalities:

They have striking commonalities:

When examining the regional variants of the rasm of such variants a striking pattern emerges: Many, if not all, manuscripts in this style have Basran variants (as we will see in a forthcoming article by @therealsidky). This might suggest a common center of production.

But besides this, they have something else striking in common: The majority of the manuscripts in the B.II group have very specific pronominal morphology.

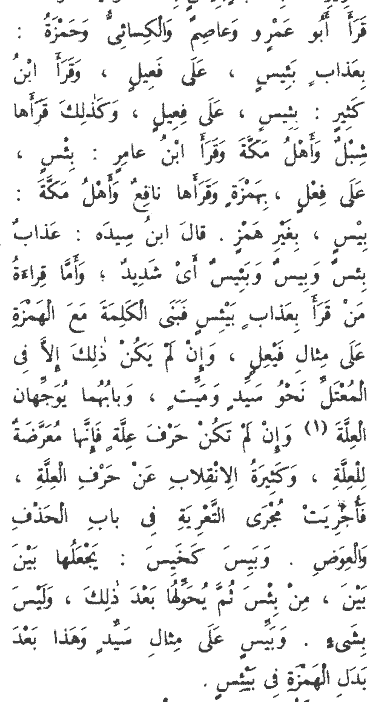

First: The plural pronouns are always long (similar to the canonical ʾAbū Jaʿfar and ibn Kaṯīr).

la-humū

yarā-kumū

etc.

First: The plural pronouns are always long (similar to the canonical ʾAbū Jaʿfar and ibn Kaṯīr).

la-humū

yarā-kumū

etc.

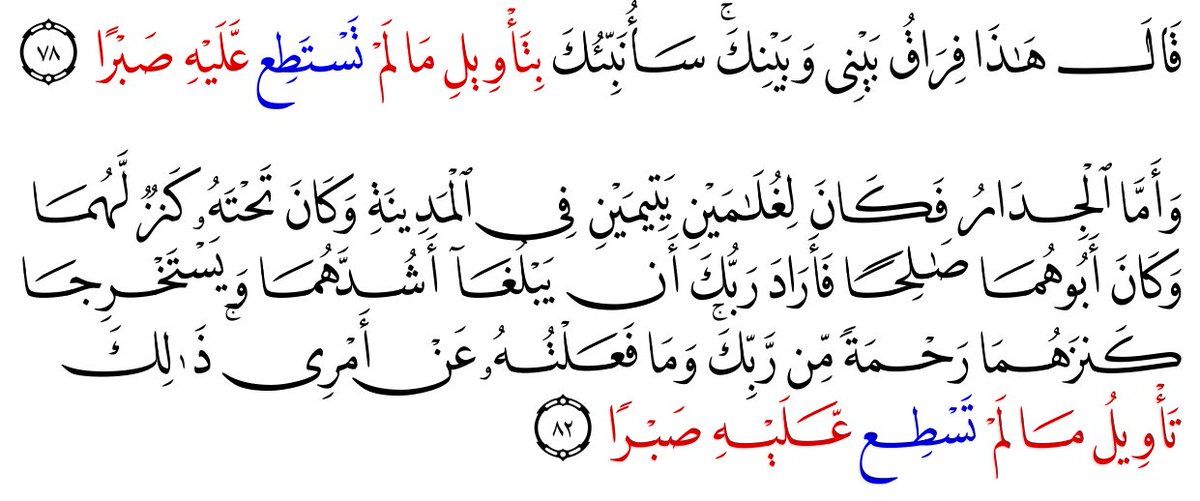

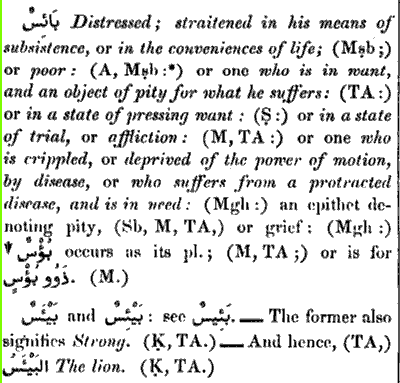

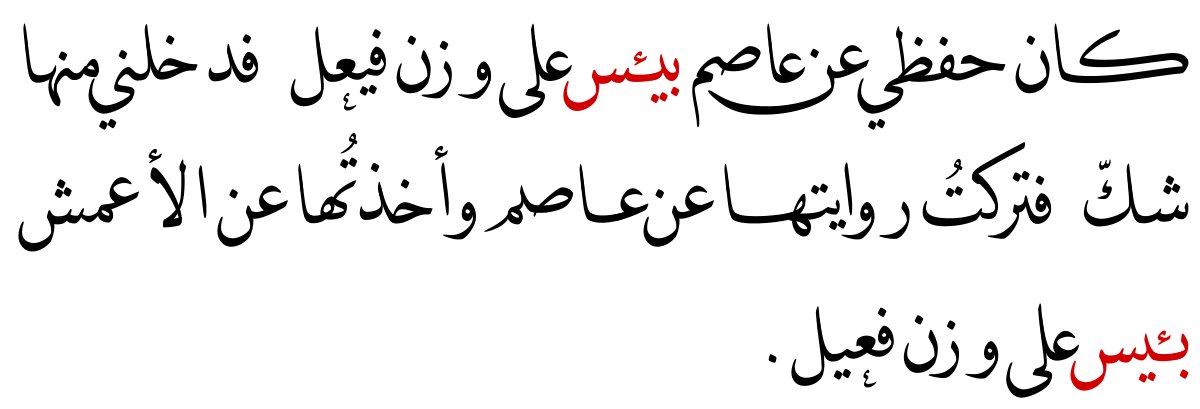

Second, the singular pronoun -hū never harmonizes when -i, -ī, or -ay precede. With one striking exception, bi-hī is always harmonized. This pattern not only does not occur among the canonical readers, it doesn't even get recorded as non-canonical!

rusuli-hū

ʿalay-hu

bi-hī

rusuli-hū

ʿalay-hu

bi-hī

It appears that this system was very popular. Me and @therealsidky have found in a forthcoming paper that the majority of B.II manuscripts have this system, and the system makes up about 15% of all manuscripts.

That's more common than Ibn Kaṯīr and ʾAbū Jaʿfar combined!

That's more common than Ibn Kaṯīr and ʾAbū Jaʿfar combined!

So at the IAS, I wish to dive deeper into this group of manuscripts, especially those that are written in the B.II script. Are the readings that share a pronominal system like this actually one and the same reading? Or are there multiple readings with this system?

This is totally possible. ʿĀṣim and Ibn ʿĀmir, among the canonical readers have identical pronominal systems, as do al-Kisāʾī and Ḫalaf.

But if they *do* represent the same reading, we have enough fragments to start to reconstruct what this reading looked like.

But if they *do* represent the same reading, we have enough fragments to start to reconstruct what this reading looked like.

What are its specific word choices? Can we find traces, albeit incomplete, in the literary sources whose reading this may have been if there is a single (or multiple) consistent systems?

Can we show on codicological grounds that there is a likelihood they come from one center?

Can we show on codicological grounds that there is a likelihood they come from one center?

And finally: can we figure out why a system once so clearly popular has been lost, seemingly completely, after canonization?

It's a lot of ambitious questions to answer in half a year, but I am currently thinking of efficient ways to tackle as much as possible!

It's a lot of ambitious questions to answer in half a year, but I am currently thinking of efficient ways to tackle as much as possible!

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more stuff like it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh