One of the features of the Quran is that certain words with no obvious rhyme or reason will occur in two different pronunciations even when the formula is essentially identical from one to the other.

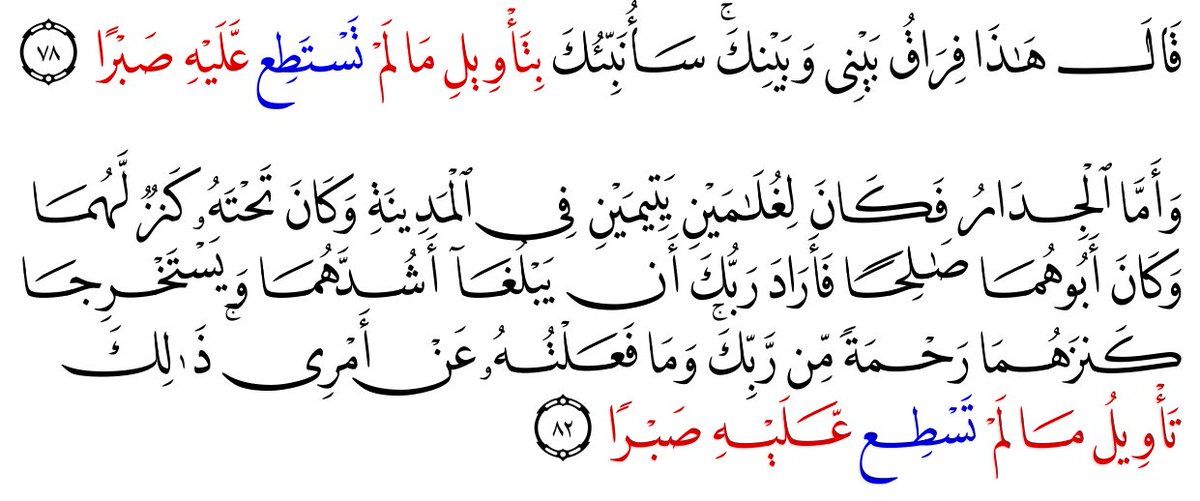

This is most notable between Q18:78 and 82.

How to understand this? Thread 🧵

This is most notable between Q18:78 and 82.

How to understand this? Thread 🧵

The end of the verse is identical save for the first occurrence having the long form of tastaṭiʿ and the second having the short form tasṭiʿ.

Of course you can come up with endless completely ad hoc case-by-case explanations, but these bring us no closer to *understanding* it.

Of course you can come up with endless completely ad hoc case-by-case explanations, but these bring us no closer to *understanding* it.

There are many cases just like this. Q6:42 and Q7:94 are formulaically parallel, yet one has yataḍarraʿūna whereas the other has yaḍḍarraʿūna.

quran.com/6/42

quran.com/7/94

Case-by-case explanations fail to explain the larger pattern that is clearly there.

quran.com/6/42

quran.com/7/94

Case-by-case explanations fail to explain the larger pattern that is clearly there.

Since no obvious answer presents itself that explains these forms in a consistent way, I do not think there is any special significance between these variants.

However, it gives insight into the oral origins of the Quran. We can see this by examining the companion readings.

However, it gives insight into the oral origins of the Quran. We can see this by examining the companion readings.

The random distribution of these variants suggests that in the register of Quranic recitation before standardization, these forms were basically pronounced in free variation. Q7:94 could have been pronounce yataḍarraʿūna and Q6:64 yaḍḍaraʿūna too, no impact on the message.

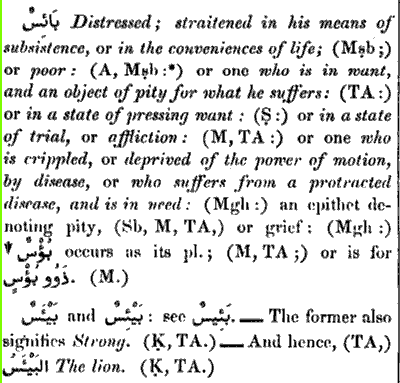

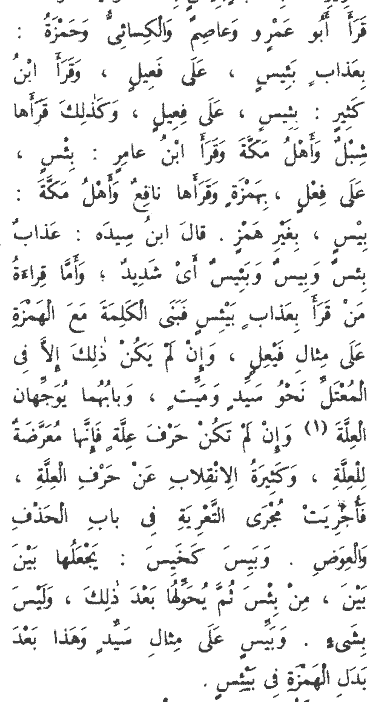

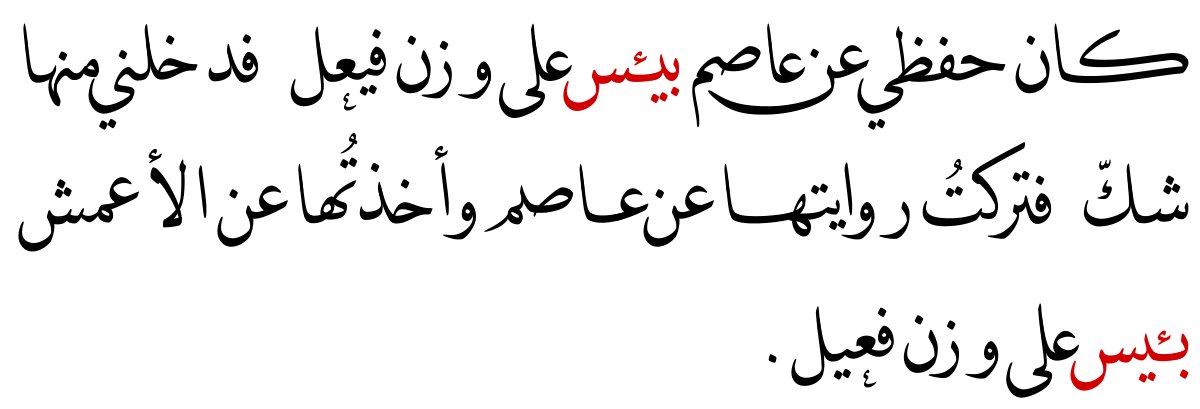

That such free variation was indeed possible and allowed is confirmed by reports of companion codices, for example for Ibn Masʿūd we find reports that he had:

fa-ddāraʾtum as fa-tadāraʾtum (Q2:72)

yaṣṣaddaqū as yataṣaddaqū (Q4:92)

iṯṯāqaltum as taṯāqaltum (Q9:38)

etc.

fa-ddāraʾtum as fa-tadāraʾtum (Q2:72)

yaṣṣaddaqū as yataṣaddaqū (Q4:92)

iṯṯāqaltum as taṯāqaltum (Q9:38)

etc.

All of these variants were simply around and acceptable for recitation, and in any single performance of the text there was a certain chance that such variant forms would come out one way or the other.

If you allow me a physics analogy: these oral variants are in "superposition"

If you allow me a physics analogy: these oral variants are in "superposition"

But much like how the wave function collapses to a single answer once it is measured, writing the text down collpases the "oral superposition". What we end up with is simply one of the possible configurations the text *could* have had, but the scribes this time landed on these.

No matter what manuscript you open up, you will always find Q6:42 as having yataḍarraʿūna, and Q7:94 yaḍḍarraʿūna. This consistent spelling difference does not carry any special significance on its own. They're just two different ways of pronouncing the same word, however:

The fact that that spelling is always reproduced in the same way does carry significance. Any person writing down the Quran could have settled on an infinite number of different configurations. That we do not see millions of different configurations in different copies means that

the text was not written down from scratch on multiple occasions. All of these manuscripts were copied from a single original document, the standard text of the Quran, which was most likely commissioned by Uthman. See also:

doi.org/10.1017/S00419…

doi.org/10.1017/S00419…

The fact that non-Uthmanic texts, like Ibn Masʿūd's text indeed show a different configuration from the Uthmanic one in these free variant options proves that there was indeed freedom to do so, and the freedom was only lost because the written form could not support it.

If you enjoyed this thread and want me to do more of it, please consider buying me a coffee.

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

ko-fi.com/phdnix.

If you want to support me in a more integral way, you can become a patron on Patreon!

patreon.com/PhDniX

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh