Today I published an op-ed in Politico with @atrembath on why @JoeBiden and @KamalaHarris are right to be skeptical of a fracking ban. It risks reviving coal when we need to phase it out ASAP and could perversely slow clean energy if not done carefully politico.com/news/agenda/20… 1/

As an aside, I really wish op-ed departments would stop rewriting headlines to make them more edgy without your permission. The title we submitted "Why Biden and Harris Are Right to Be Skeptical of a Fracking Ban"... 1.5/13

The op-ed is in part a distillation of this exceedingly long twitter thread the other week, so I'd suggest checking that out for details if you haven't seen it yet:

https://twitter.com/hausfath/status/13143756521123594242/13

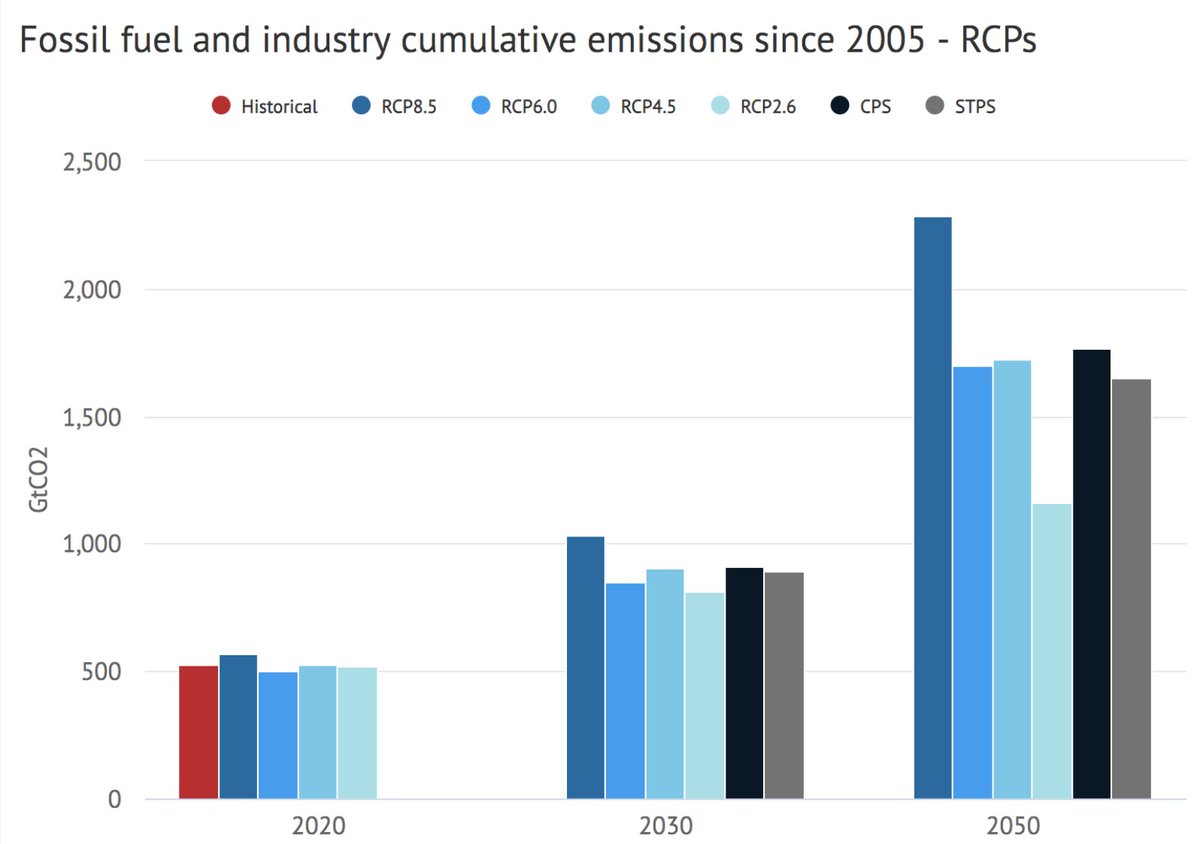

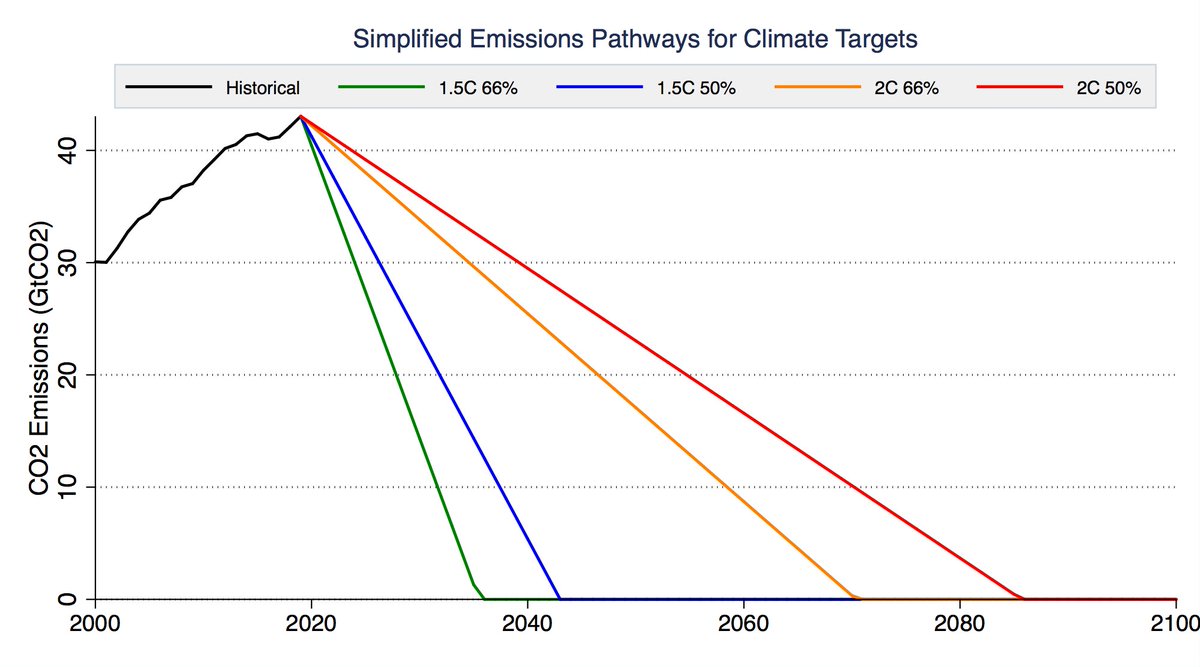

To summarize the main points of that thread, we need to ultimately move away from gas (at least without CCS) to meet @JoeBiden's plan to decarbonize electricity by 2035. But banning fracking today would drive up gas prices and increase coal use in the short term. 3/13

Right now coal plants are operating at below 50% capacity, and can (and have) easily ramp up if gas prices increase. Coal's twice as carbon intensive as gas, and plays poorly with renewables. We need to prioritize shutting down coal and worry about existing gas later. 4/13

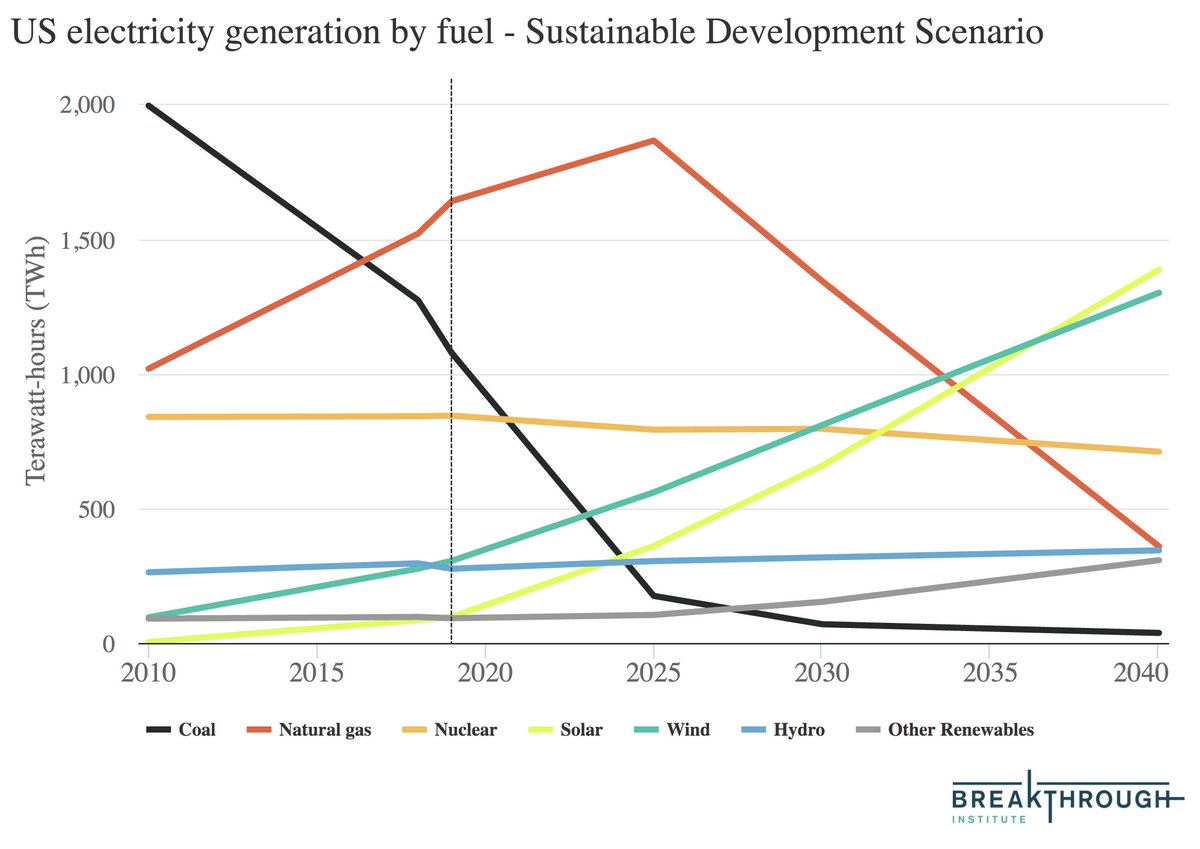

Gas on the other had has been the biggest driver of coal retirements. Its low capital costs (and relatively higher operational costs) make it an ideal energy source to fill in gaps in a high variable renewable energy future, at least until grid-scale storage becomes cheaper. 5/13

We see this in energy models that try to determine optimal decarbonization pathway. For example, the @IEA's 2020 WEO Sustainable Development Scenario prioritizes closing down coal, with gas falling later on: 6/13

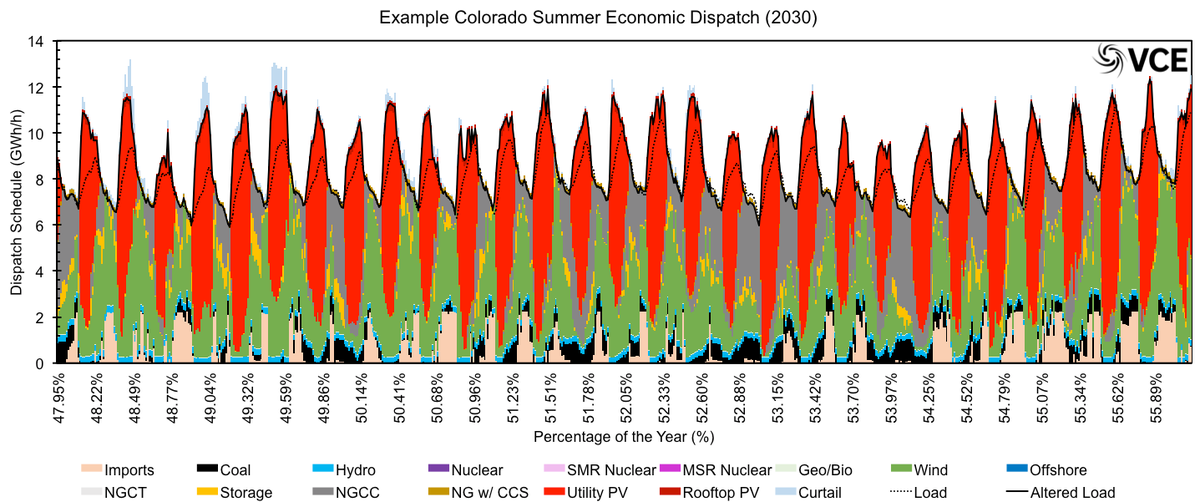

Similarly, grid modeling work by @DrChrisClack and his team has gas playing an important role through at least 2030 in balancing out renewables, being slowly replaced over time with storage (though some challenges in seasonal storage remain). vibrantcleanenergy.com/wp-content/upl… 7/13

At the same time if we really want to decarbonize the electricity sector by 2035, we need to take a hard look at any new gas plants being built going forward, at least without CCS or easy retrofit capability. We have a lot of excess gas capacity today in most regions. 8/13

We also need to do a much better job dealing with the problem of fugitive methane from gas infrastructure. It is a solvable problem, and there is evidence that a small fraction of "super-emitters" account for a large portion of overall leakage. 9/13

Right now @JoeBiden and @KamalaHarris propose allowing no new oil and gas development on public lands. This would be mostly symbolic, as the vast majority of production already occurs on private land. 10/13

However, its important that any future legislation on this issue focus any policies restricting supply on the actual production of oil and gas, not on the technology of fracking itself – where a lot of the environmental community focuses its messaging. 11/13

A ban on fracking on public lands would severely impact enhanced geothermal, a very promising clean energy technology that often relies on fracking as a way to increase the surface area of underground formations that can heat up water. thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/… 12/13

Unlike oil and gas production, a sizable portion of enhanced geothermal potential is on public lands in the Western US. Its important that we don't throw the proverbial geothermal baby out with the fracking bathwater. 13/13

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh