1/ Watch how coronavirus spreads indoors in a room, a bar, and a classroom

A short article in @FastCompany about the @elpaisinenglish aerosol infographics, that explains the caveats well:

fastcompany.com/90569949/watch…

A short article in @FastCompany about the @elpaisinenglish aerosol infographics, that explains the caveats well:

fastcompany.com/90569949/watch…

2/ "The numbers in the visualization shouldn’t be taken as certainties. Though the model is based on peer-reviewed science, it’s still unclear exactly how much virus an infected person sheds, and how much ill-fitting cloth masks reduce the risk of catching the disease...

3/ ... The model also assumes that everyone maintains a two-meter distance from each other at all times.

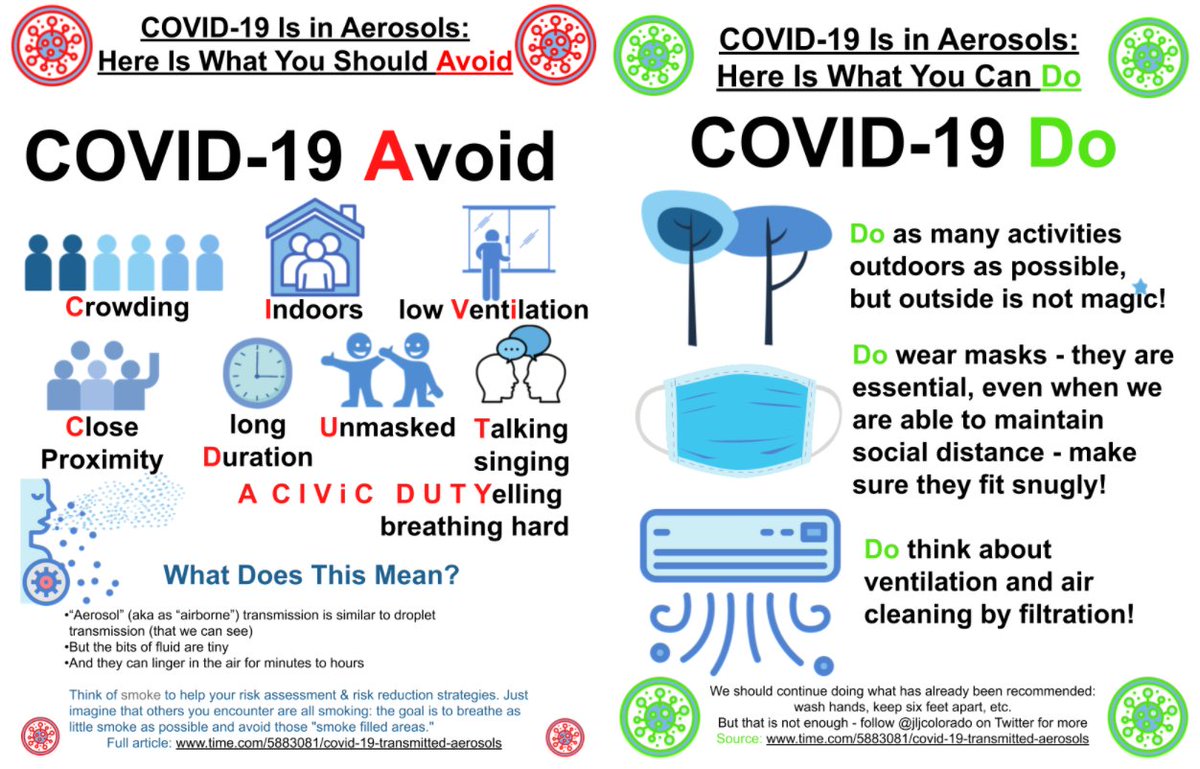

“So we trust the order of magnitude of the results and especially the relative strengths of different actions such as increasing ventilation or wearing masks...

“So we trust the order of magnitude of the results and especially the relative strengths of different actions such as increasing ventilation or wearing masks...

4/ but not the precise infection probabilities,” Jimenez said in a June press release. “Different actions have very different costs, so the hope is that the tool can help allocate limited resources to reduce the risk of infection most effectively.”

5/ That is the first thing that you'll read if you look at the model itself as well, which is publicly available at tinyurl.com/covid-estimator

6/ There seems to have been some confusion about the @elpaisinenglish article. I did not write the article, it was written by @javisalas and @Mariano_Zafra. They came up with what they wanted to show, and I helped them make sure it was all correct and as realistic as possible.

7/ Being a scientist, I would have added the caveats above to explain what was being simulated (shared room air transmission) and not (close proximity transmission). And the fact that we trust much more the relative effect of ventilation, masks etc.

8/ But, as clearly stated in the estimator, we trust much less the magnitude of infection, which can vary an order of magnitude.

The model is "calibrated" to real outbreaks (choir, restaurant, bus...) and thus situations in which people were quite infective.

The model is "calibrated" to real outbreaks (choir, restaurant, bus...) and thus situations in which people were quite infective.

9/ Not everyone infected is very infective, partially because of timing in the disease:

https://twitter.com/DiseaseEcology/status/1271281853391966213

10/ And we also know that some people are high aerosol emitters, x10 more than others (nature.com/articles/s4159…).

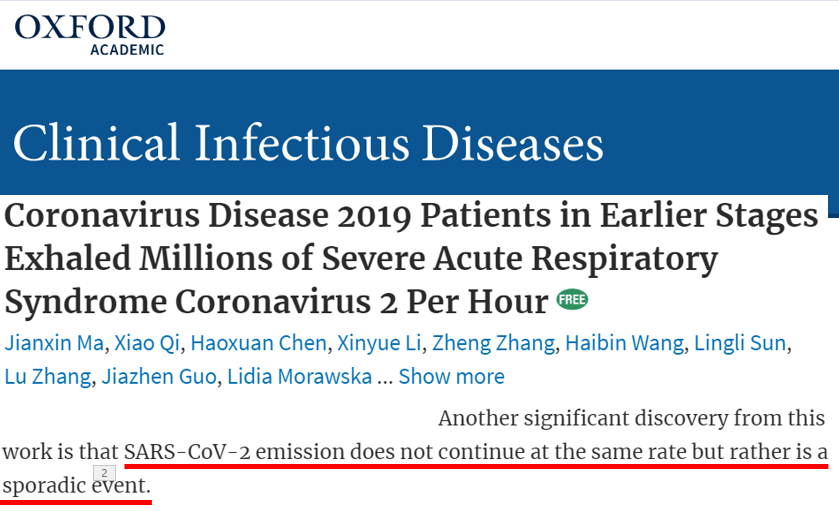

And we know that virus emission from infected people is **sporadic** (doi.org/10.1093/cid/ci…).

And we know that virus emission from infected people is **sporadic** (doi.org/10.1093/cid/ci…).

11/ So we know infectivity of infected people is hugely variable. So we don't expect the same infection everywhere. The model simulates favorable infectivity for an outbreak. Which I'd argue, is what's most interesting and important to simulate.

12/ Frankly I didn't expect the article would get the level of attention that it has gotten. With attention comes criticism. I hope this thread dispels some of the misunderstandings that seemed to underlie some of the criticisms.

I may write a longer one with the bigger picture

I may write a longer one with the bigger picture

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh