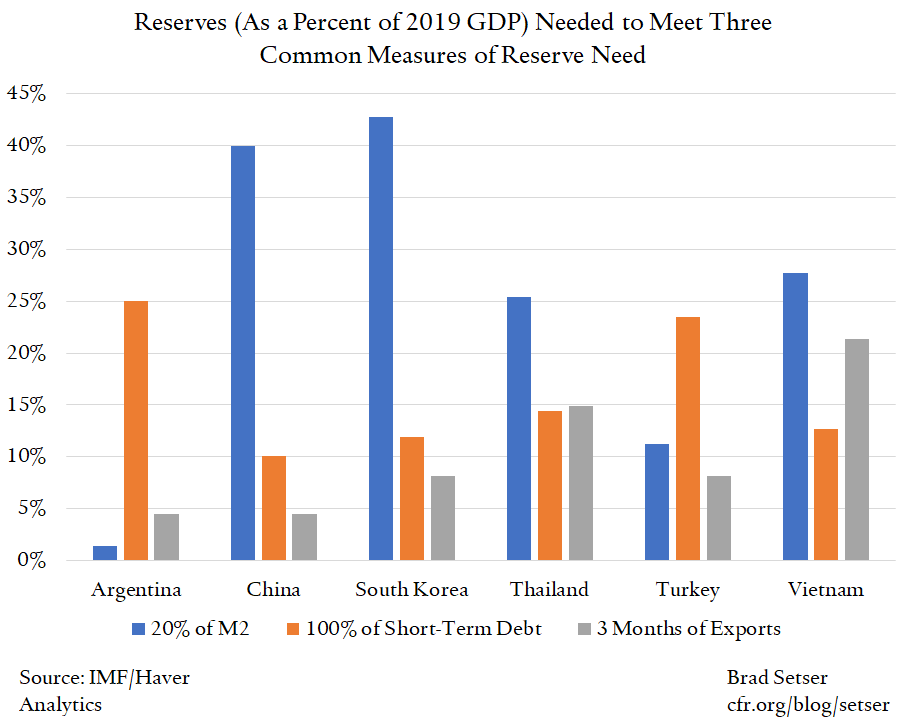

The IMF needs to junk its current metric for assessing reserves.

It simply doesn't work. It dilutes what should be strong signals of extreme vulnerability.

cfr.org/blog/it-time-s…

It simply doesn't work. It dilutes what should be strong signals of extreme vulnerability.

cfr.org/blog/it-time-s…

The IMF's metric (without adjustments) suggested that Turkey had a slightly stronger reserve position that China going into 2020. Which is absurd.

(and yes, I do read the details of the IMF's ESR!)

(and yes, I do read the details of the IMF's ESR!)

The reason is simple: measures of reserve need based on broad money (m2) imply that countries with big domestic deposit bases (China, Korea and the like) need a ton of reserves, while countries with small banking systems (like Argentina) need far fewer

But the countries with small banking systems tend to have trouble financing fiscal deficits or rapid credit growth domestically, and often end up having current account deficits and lots external debt. In practice they need more not fewer reserves than the big surplus countries

Countries with relatively small banking systems (modest m2 to GDP) tend to have large amounts of short-term debt ...

Turkey and Argentina are cases in point. I believe their reserve need is a lot closer to reserves v STD than reserves v M2!

Turkey and Argentina are cases in point. I believe their reserve need is a lot closer to reserves v STD than reserves v M2!

So the IMF's composite indicator (by blending two indicators that are often inversely correlated) muddies up any strong signal --

And when it comes to assessing vulnerabilities, I think you really need to isolate the strong signals.

And when it comes to assessing vulnerabilities, I think you really need to isolate the strong signals.

And because countries with large banking systems with lots of domestic currency deposits (a high m2 to GDP) tend to run external surpluses and countries with small banking systems tend to run deficits ...

The IMF's metric systematically raises the estimated reserve need of BoP surplus countries while systematically lowering the estimated reserve need of BoP deficit countries.

That is basically backwards. Deficit countries actually are the ones who need more reserves.

That is basically backwards. Deficit countries actually are the ones who need more reserves.

This is in fact an intellectual hill that I am willing to die on ...

The crazy China v Turkey result highlights a systemic problem in the current metric.

The crazy China v Turkey result highlights a systemic problem in the current metric.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh