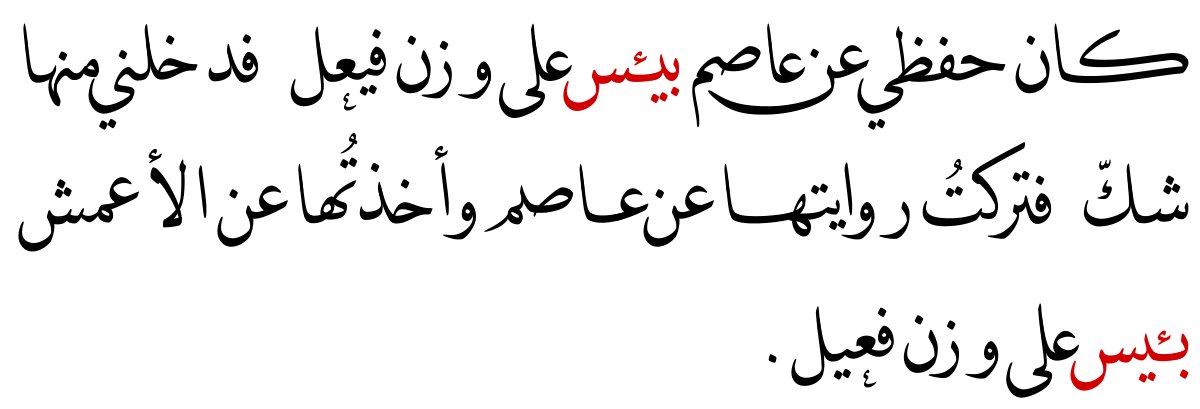

@theodorebeers @ibn_kato The rule according to the Arab grammarians, and normative Classical Arabic is that after a heavy syllable the suffixes should be -hu/-hi, and after short syllables the suffixes should be -hū/-hī. This is not just as poetry, but also prose (including the Quran).

@theodorebeers @ibn_kato In fact poetry is one of the prime contexts that are cited where the rule might be broken and short vowel -hu and -hi may be used after light syllables, and -hū and -hī may be used after heavy syllables!

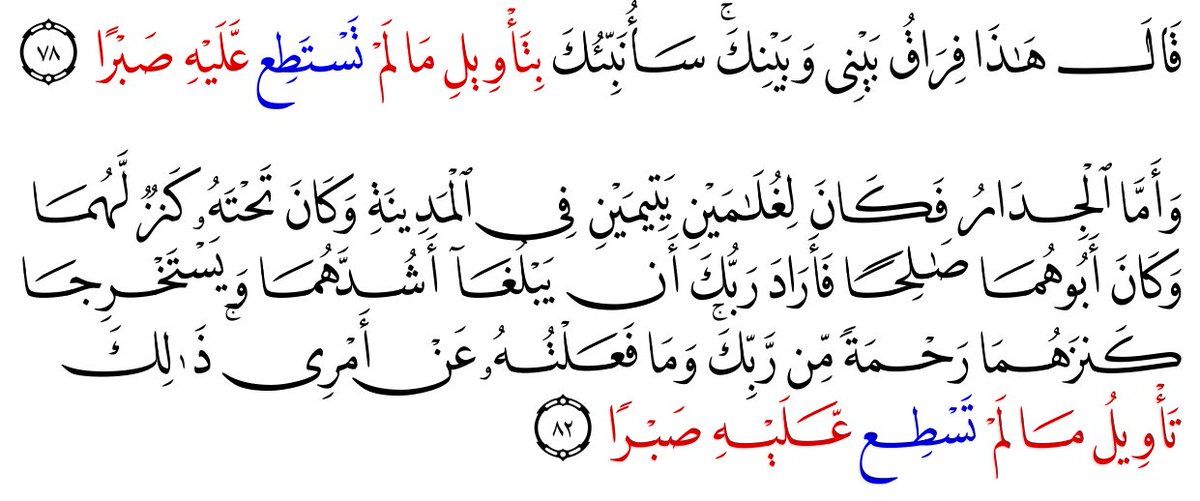

@theodorebeers @ibn_kato Especially Maghrebi manuscripts, but occasionally also Mashreqi manuscripts can be quite precise about this. Here funūni-hī with miniature yāʾ on top of the hāʾ to mark length in a copy of Risālat ibn Abī Zayd.

Strangely manners for expressing this were never developed for -hū.

Strangely manners for expressing this were never developed for -hū.

@theodorebeers @ibn_kato Actually I'm lying! taʿtafida-hū with miniature wāw below the hāʾ!

It's the Mashreq where they don't usually have a way of expressing it. While the -hī is frequently written with a dagger alif below the hāʾ instead of normal kasrah.

It's the Mashreq where they don't usually have a way of expressing it. While the -hī is frequently written with a dagger alif below the hāʾ instead of normal kasrah.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh