A lot of time gets wasted on the polemics of the stability of transmission of the Hebrew Bible and the Quran.

Instead of arguing without evidence let's compare a section the Masoretic Text to a 1QIsaª and the Cairo standard text to the Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus. 🧵

Instead of arguing without evidence let's compare a section the Masoretic Text to a 1QIsaª and the Cairo standard text to the Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus. 🧵

I've selected a 1QIsaª because it is really quite close to the standard Masoretic text. The point of comparison are Isaiah 40:2-28 (949 letters in total) and the Q3:24-37 (1041 letters in total). In number of letters they are therefore pretty similar.

Here is a comparison of the Isaiah scroll with the Masoretic text. Green = extra letter in the scroll, yellow = missing letter, blue = different letter, magenta and red are later additions and deletions.

The texts are very similar, but regardless differences are visible.

The texts are very similar, but regardless differences are visible.

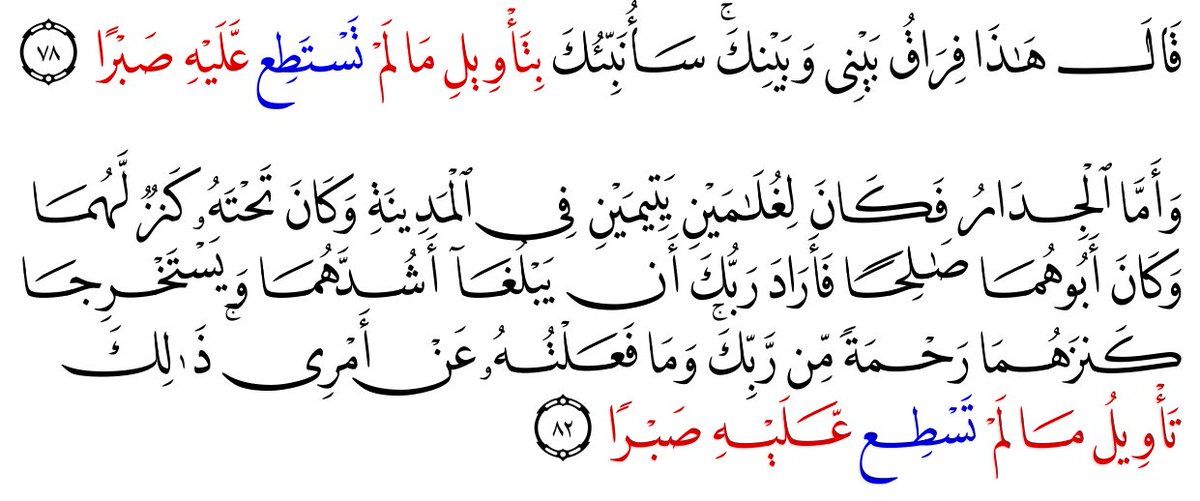

Now compare this to a larger portion of text in terms of characters in the CPP (produced somewhere between 650 and 700 CE) compared to the standard text of 1924CE. The difference is striking. 11x a letter is missing compared to the standard text, 3x times there is an extra letter

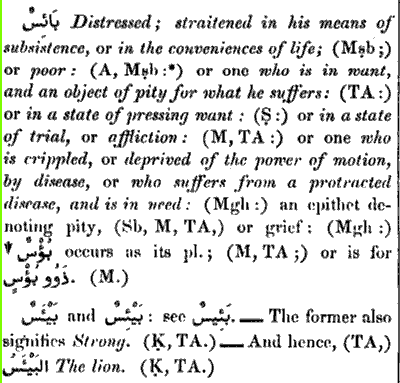

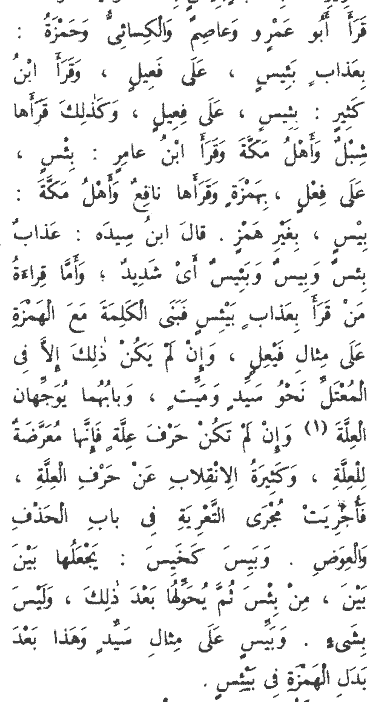

Every single difference between the standard text and the CPP concerns a the same letter: the ʾalif, a letter that came to be more commonly written in later Arabic. The Hebrew portion concerns a myriad of different letters and sometimes even different words.

The difference in time between 1QIsaª (1st c. BCE) and the Masoretic text (10th c. CE) is pretty comparable to the Cairo Edition and the CPP, yet the difference in the stability of the text is vastly different.

This difference isn't miraculous: the Quran's text was canonized early and had state support to maintain that to its minute details in a way that the Hebrew Bible (not to speak of the new testament!) simply was not.

I hope this visual presentation brings that point home.

I hope this visual presentation brings that point home.

You can check out 1QIsaª here: dss.collections.imj.org.il/isaiah (column 33 is the relevant section).

the CPP here: gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv… (3r and some of 3v is the relevant section).

the CPP here: gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv… (3r and some of 3v is the relevant section).

Continued: Some replies have pointed out that comparing 1QIsaª against the standard text and comparing that to early Quranic manuscripts and the print edition isn't quite a faire comparison, because 1QIsaª is quite exceptional in its deviations from the Masoretic text.

This is true. If we would do the same exercise with 1QIsaᵇ which is of the Proto-Masoretic text type (same as the standard text today) we would see a quite similar result as the one we see between the CPP and the modern Cairo print. Images from Tov (1992).

But the important point of this: When it comes to the Quran, you cannot even pick an unfair comparison. Up until now there is only one text that doesn't belong to the Uthmanic tradition (the lower text of the Sanaa Palimpsest). All the other ones are virtually identical.

In fact if we pick two roughly contemporary (7th century) manuscripts like Or. 2165 and the CPP, the similarity is striking. Here I have marked all the differences between Q7:42-53 in these two manuscripts in Yellow.

(you've not gone colour blind, there are no differences)

(you've not gone colour blind, there are no differences)

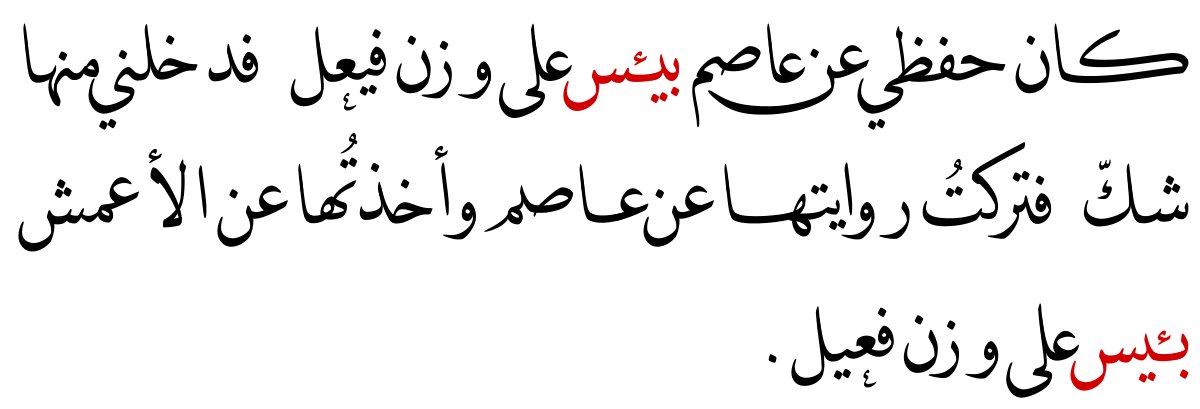

So what about this Sanaa Palimpsest? How dissimilar is it from the Uthmanic text type? We can compare the lower and upper text of the same section and see how similar they are: This is the end of Q8:73 up to the beginning of Q9:7. Despite differences the texts are still close.

The closeness of the two texts is enough that by Biblical standards (and certainly by New Testament standards) these two texts would presumably be considered the same text type. By Quranic standards this kind of deviation is totally unheard of outside of the palimpsest.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh