"Music, Sense and Nonsense: Collected Essays and Lectures", por Alfred Brendel.

Capítulo: “Conversations - Talking to Brendel with Jeremy Siepmann”

open.spotify.com/playlist/2PJMD…

Capítulo: “Conversations - Talking to Brendel with Jeremy Siepmann”

open.spotify.com/playlist/2PJMD…

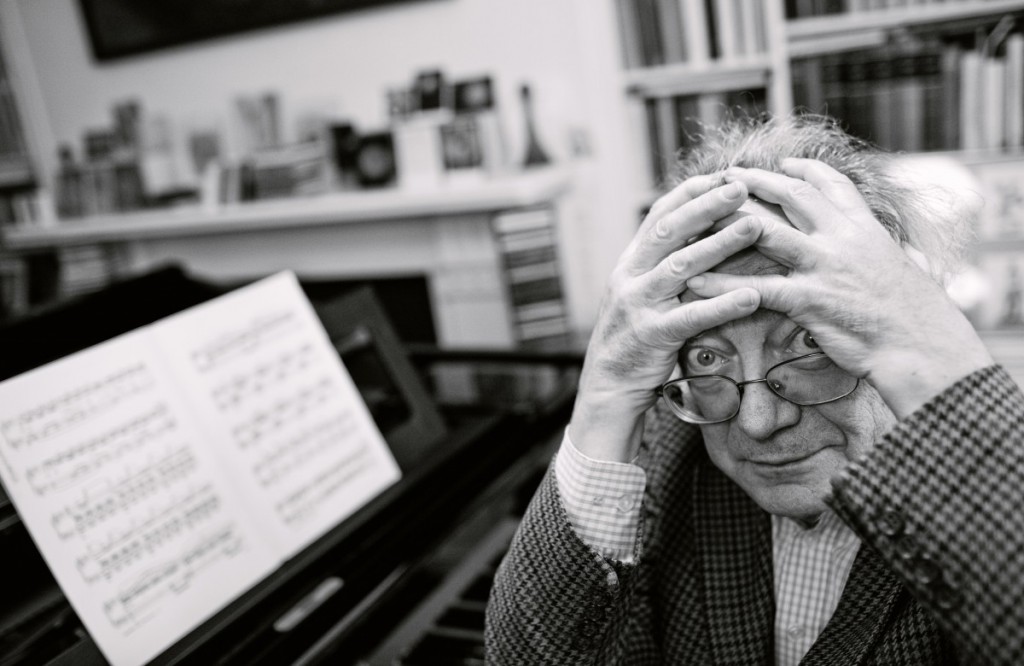

Ya casi llegamos al final de este maravilloso libro. En esta sección, Brendel comparte varias entrevistas. La primera de ellas fue en 1972 con Jeremy Siepmann, músico, locutor, articulista y autor de varios libros sobre música.

Si bien después de 377 hojas ya tenemos una buena idea sobre las opiniones de de Brendel sobre la música y el quehacer musical, en esta entrevista revela varios puntos de vista.

Sobre si disfruta interpretar música, Brendel responde que sí, sobre todo en los últimos años, “when I’ve had the impression that much of what I do comes across. Of course, one very rarely knows if the right things come across)”.

Sobre si los intérpretes existen para vincular al compositor con el público, Brendel afirma que le interesa más la relación del intérprete con el compositor que con el público: “What fascinates me is to make sense of a piece of music while it sounds”.

Sobre si el intérprete debería “educar” a su público, Brendel considera que se debe hacer clarificar la pieza lo más posible. Pero si el público siente que el intérprete quiere educarlo, el caso está perdido. Si se quiere educar al público, este no debe siquiera darse cuenta.

Sobre si el análisis musical tiene algún valor al intérprete, si bien es necesario tener un sólido conocimiento musical, el intérprete no debe considerar el análisis musical como la llave al tipo de intuición que permite una gran interpretación.

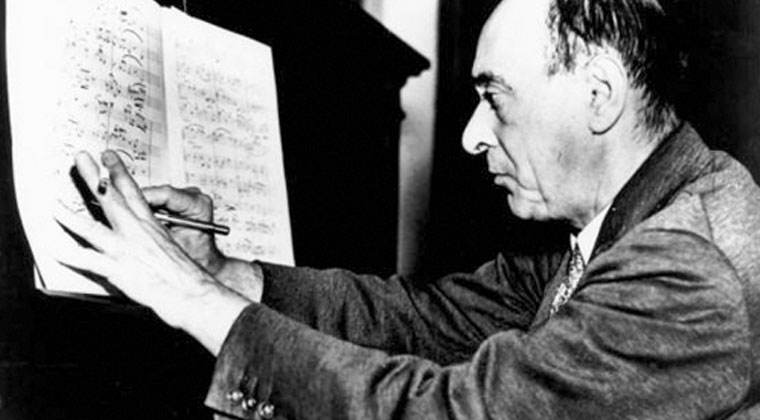

“It was Schoenberg who said, in a letter, that formal analysis is often overrated because it shows how something is done, not what is done. This, from one of the supreme analysts, is something valuable, I think”.

Sobre si la música grabada y en vivo requieren ser escuchadas distintamente, Brendel considera que si bien existen ciertas diferencias básicas, en su caso mientras más progresaba en sus grabaciones, más trataba de tocar como si estuviera en un concierto ante un público.

“Many more concerts should be recorded and issued on disc, with all their imperfections and coughing and so on. As far as piano recordings are concerned, the over-refinement of our tools nowadays seems sometimes to be a disadvantage.”

Sobre si la gesticulación al interpretar tiene alguna función musical, Brendel considera sí la tiene. Cuando se vio en televisión por primera vez, se dio cuenta que sus gestos contradecían completamente lo que hacía y lo que quería hacer musicalmente.

“I then had a mirror made, a big standing mirror, which I put beside the piano, not really making me visible all the time, but always there; unconsciously, one noticed things. It helped me to co-ordinate what I wanted to suggest with my movements with what really come out”.

Sobre la relación con sus grabaciones, Brendel considera que son “a kind of offspring of which one can’t, unfortunately, say that one has to nurse them until they grow up and then forget them as soon as possible and let them lead their own live…

They lead their own lives at once, and are scarcely ever grown up! There’s always something infantile about a record, al least as far as the artist is concerned. Records are interesting to learn from but not always to enjoy”.

Sobre el escribir sobre música, Brendel considera que no se debe ser arrogante: “That may seem very irrelevant, but I think it’s very important. If one decides to talk about something as elusive as music…

… something which is so difficult to grasp in words without talking nonsense all the time and being imprecise to an enormous degree, and personal to a degree which is no use to anyone, then one has to be modest about it”.

Sobre intérpretes que intentan ser originales distorsionando lo que el compositor indica en la partitura, Brendel considera que es una tontería. “If one sheds new light on music, it should be the outcome of an effort, not the input!”

Sobre si ha considerado dirigir, si bien Brendel se interesa por la dirección y sus técnicas, e incluso se imagina a sí mismo dirigiendo, nunca lo haría: “I think I would be too shy to attempt to impose something on an orchestra without being completely professional”.

Sobre si pudiera cambiar algo en su vida profesional: "I don't know. So far I don't feel at all exploited. I play a lot, though not as much as some other people, but I play because I like it. I have a lot of other interests, of course for which time will always be too short".

@threadreaderapp unroll

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh