🎂🎂Birthday alert:

2020 marks the 30th birthday of the term Washington Consensus, coined by J Williamson to refer to "what Washington means by reform" in dev countries.

In new article, S Babb & I take stock (forthc. in Annual Rev Soc).

A thread.

PDF: bit.ly/WashCon

2020 marks the 30th birthday of the term Washington Consensus, coined by J Williamson to refer to "what Washington means by reform" in dev countries.

In new article, S Babb & I take stock (forthc. in Annual Rev Soc).

A thread.

PDF: bit.ly/WashCon

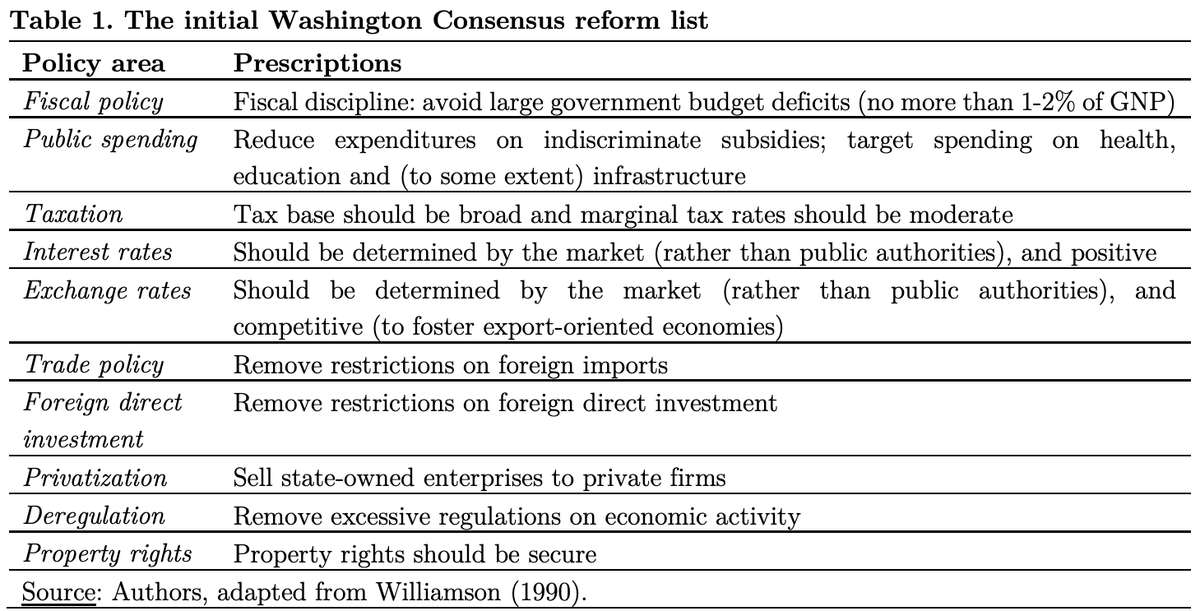

Let's start with the basics: what was the Washington Consensus?

For supporters, it was shorthand for the list of reforms that were necessary to overcome debt problems and unlock the development potential of low- and middle-income countries.

For supporters, it was shorthand for the list of reforms that were necessary to overcome debt problems and unlock the development potential of low- and middle-income countries.

For opponents, the term was used to describe the scourge of radical market-oriented reforms that trapped countries in conditions of dependency and underdevelopment.

As Naomi Klein put it in the Shock Doctrine:

As Naomi Klein put it in the Shock Doctrine:

But by friends and foes alike, the Washington Consensus was seen as an attempt at fundamental, unprecedented and large-scale reorientation of developing-country policies.

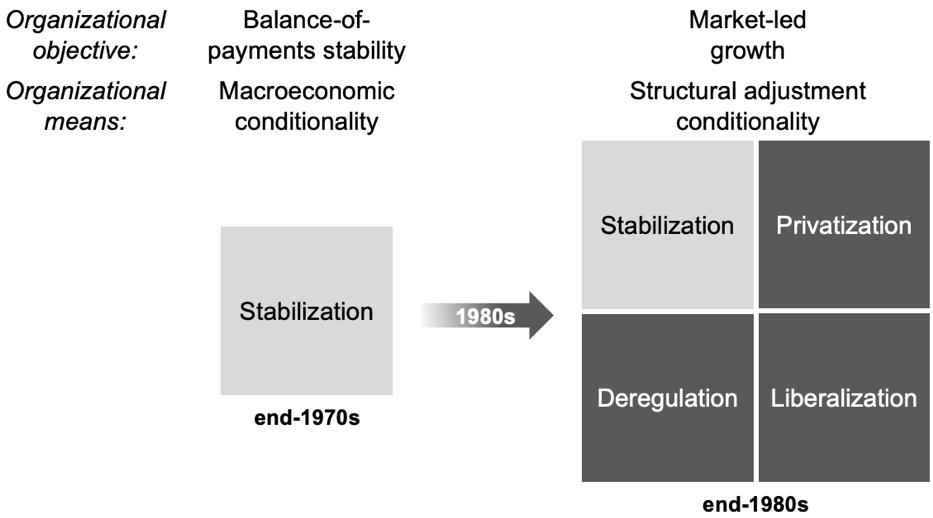

While the term itself was coined in 1990, it refers to policies that started to be promoted in the 1980s.

While the term itself was coined in 1990, it refers to policies that started to be promoted in the 1980s.

Somewhat dispassionately, we conceptualize the Wash Con as a coordinated campaign for the global diffusion of free-market policies, organized around the resources and authority of int'l organizations.

And ask two questions: how did it become dominant, and what happened to it?

And ask two questions: how did it become dominant, and what happened to it?

Tracing the rise of the Wash Con requires engagement with 3 distinct issues:

First, it was built around the mobilization of int'l bureaucracies to promote market-liberalizing policies around the world.

In making this happen, the role of the US was key:

First, it was built around the mobilization of int'l bureaucracies to promote market-liberalizing policies around the world.

In making this happen, the role of the US was key:

https://twitter.com/Kentikelenis/status/1136588407621193730?s=20

Second, the Wash Con relied academic ideas about states & markets.

Per Williamson, these ideas formed “the common core of wisdom, embraced by all serious economists, whose implementation provides the minimum conditions for a developing country to prosper”

Per Williamson, these ideas formed “the common core of wisdom, embraced by all serious economists, whose implementation provides the minimum conditions for a developing country to prosper”

But these ideas were not naturally championed by their organizational promoters—they needed to be hammered through.

In WB, this was done by appointing Anne Krueger as chief economist: she fired staff with alternative views & shifted research focus away from issues of inequality

In WB, this was done by appointing Anne Krueger as chief economist: she fired staff with alternative views & shifted research focus away from issues of inequality

Third, politics matter: the Wash Con was a projection of US power

In post-Cold War era, US econ interests (vs perceived security threats) took front stage in foreign pol.

This made the role of big banks and business much more important, and shrunk policy space for dev countries

In post-Cold War era, US econ interests (vs perceived security threats) took front stage in foreign pol.

This made the role of big banks and business much more important, and shrunk policy space for dev countries

Even Jagdish Bhagwati, a prominent free-market proponent, drew on Marxist sociology to summarize what was going on:

Over 1990s, original list of reforms grew & grew. Governance and legal issues, central bank independence, civil service restructuring, social policies…

A crusade by the triumphant capitalist bloc to exercise seemingly unlimited editorial authority over dev-country institutions.

A crusade by the triumphant capitalist bloc to exercise seemingly unlimited editorial authority over dev-country institutions.

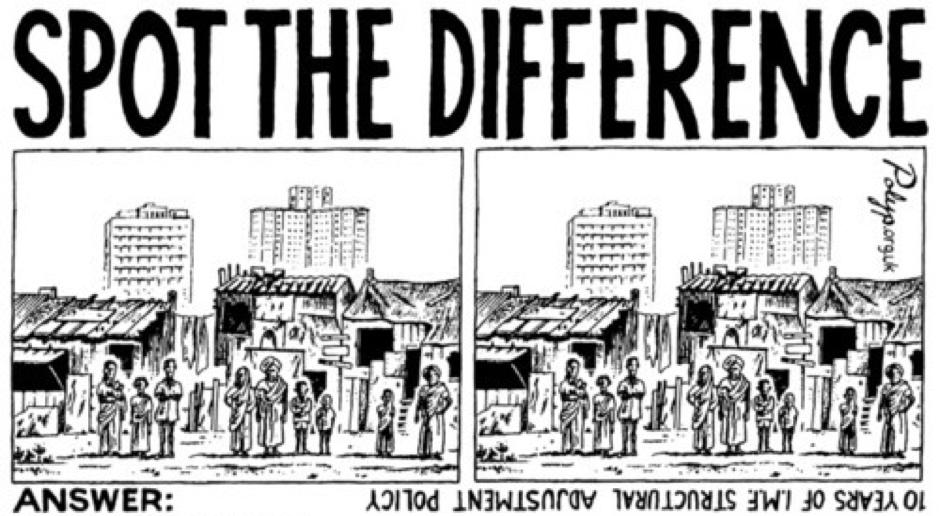

Did the Wash Con live up to its promise? Depends on where you look and whom you ask.

But proponents and detractors alike acknowledge its extraordinary impact: it succeeded in reshaping countries’ political economies, for better and for worse.

But proponents and detractors alike acknowledge its extraordinary impact: it succeeded in reshaping countries’ political economies, for better and for worse.

Trade barriers evaporated, labour protections dismantled, state-owned industries & nat resources privatized, market-friendly laws introduced…

Many contemp debates around economic, social & environmental justice—and on rising inequalities—can be traced back to these reforms

Many contemp debates around economic, social & environmental justice—and on rising inequalities—can be traced back to these reforms

So, what happened to this influential policy paradigm?

One line of argument points to the unraveling of the Washington Consensus. It can no longer credibly be said that there is a unified development policy paradigm that inspires unanimous support.

As @rodrikdani put it:

One line of argument points to the unraveling of the Washington Consensus. It can no longer credibly be said that there is a unified development policy paradigm that inspires unanimous support.

As @rodrikdani put it:

In part, this is linked to shifts in distribution of global econ power—broadly associated with weakening of US hegemony.

Washington’s ability to prescribe policies is not what it used to be, and there are new actors (see China) that developed by rejecting Wash Con-style policies

Washington’s ability to prescribe policies is not what it used to be, and there are new actors (see China) that developed by rejecting Wash Con-style policies

A second line of argument posits that, rather than going away, the Washington Consensus has gone undercover.

The new “undercover Washington Consensus” lacks monolithic backing of economists or enabling US unipolarity

Rather, it has become durably inscribed in the infrastructure of glob institutions—in the expansion of their mandate/ambitions & the persistence of their org technologies

Rather, it has become durably inscribed in the infrastructure of glob institutions—in the expansion of their mandate/ambitions & the persistence of their org technologies

See case of research @ IMF & WB: While research has become diversified, core operations are walled-off from potentially disruptive influence of new ideas.

Eg, IMF simultaneously publishes work on determinants of inequality & pursues ineq-augmenting policies in lending progs

Eg, IMF simultaneously publishes work on determinants of inequality & pursues ineq-augmenting policies in lending progs

Meanwhile, within IMF/WB research teams continues a curation of ideas to select out those that conflict with policy.

At the WB, two recent chief economists resigned after clashing with management over content of research publications and country benchmarking exercises.

At the WB, two recent chief economists resigned after clashing with management over content of research publications and country benchmarking exercises.

Also,see billions to trillions initiative, premised on using ODA to spur private investment in dev-countries

To attract such investment, dev-country govts are urged to “de-risk”: remove regulations, privatize assets & provide subsidies. See @DanielaGabor: osf.io/wab8m/

To attract such investment, dev-country govts are urged to “de-risk”: remove regulations, privatize assets & provide subsidies. See @DanielaGabor: osf.io/wab8m/

Where does all this leave us?

Reports of the death of the Washington Consensus may have been greatly exaggerated.

Reports of the death of the Washington Consensus may have been greatly exaggerated.

Just a few months ago, WB president Malpass (a veteran of the first era of the Washington Consensus) suggested countries receiving Covid-19 support would need to open up their markets:

The technology of the Wash Con—policy-based lending, country strategies, Bank-Fund collaboration, and so on—remains encoded in the infrastructure of global economic governance.

Given major econ, social and env challenges, it is time to revisit whether all this is fit for purpose

Given major econ, social and env challenges, it is time to revisit whether all this is fit for purpose

And here's a link to the article again.

PDF: bit.ly/WashCon

PDF: bit.ly/WashCon

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh