THREAD. A seriously muddy walk across one of the high, flat, clay plateaux of S Cambs. today, was full of reminders that this land, too heavy for ox-drawn ploughs, was medieval common pasture studded with managed woodland..

2. The fields were full of water despite being at the top of the hills - too flat to drain well, studded with small pockets of low land that made temporary ponds..

3. Coming across Eversden Wood in this waterlogged landscape reminded me of the great Oliver Rackham’s truism that #medieval #woods are not found on land that’s good for woods, but on land that’s no good for anything else - and of his advice on how to recognise them..

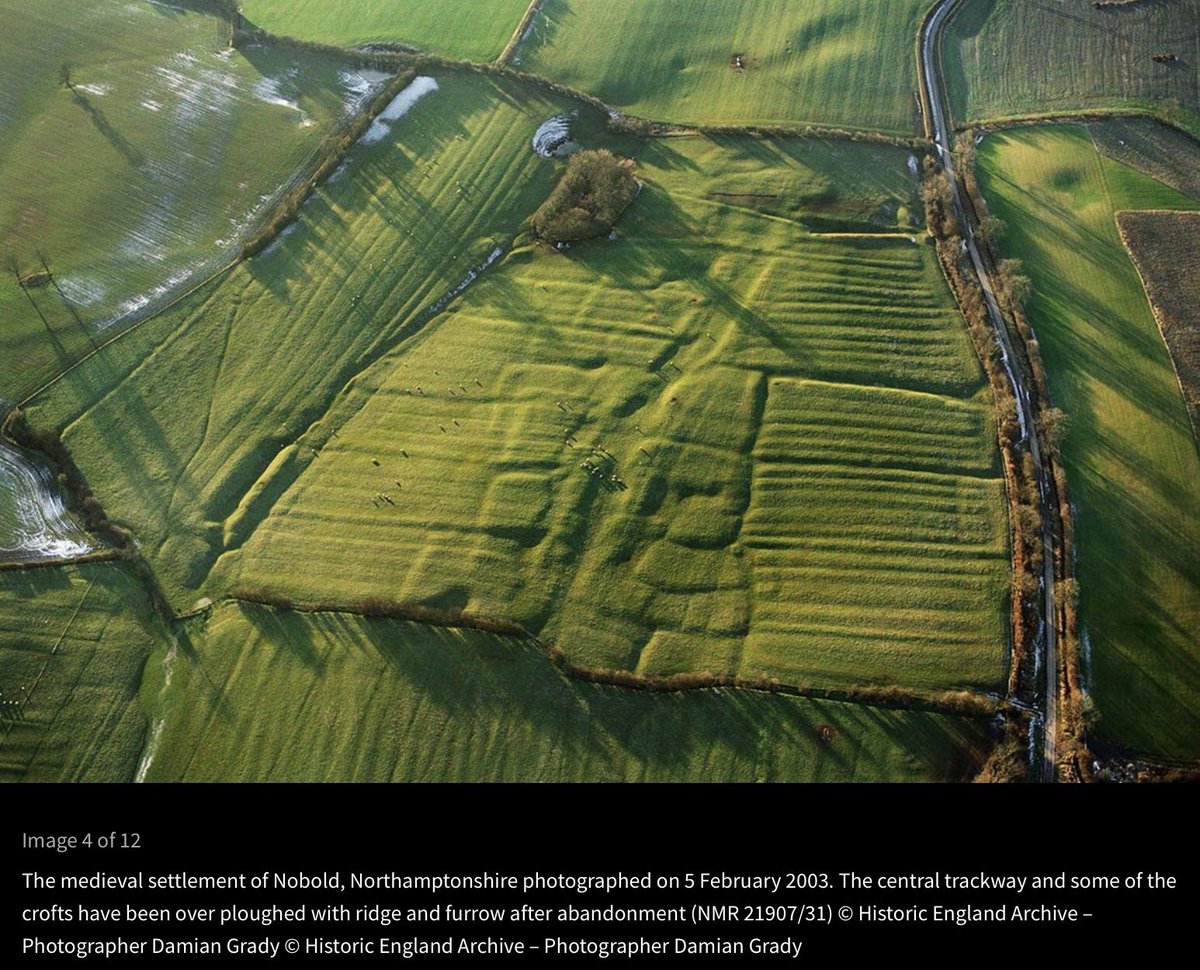

4. First, he suggested that ancient woods tend to have irregular boundaries: either sinuous (like the N boundary of Eversden wood) or zigzag with abrupt corners (like its S boundary). The curves along the N boundary reflect those of medieval ploughlands where men desperate ..

5. .. to make living in the land-hungry later 13th/early 14thC grubbed up woodland for arable fields. Sometimes those fields were lost to woods again, as the now-wooded ridge & furrow in the lower figure shows.

6. Sometimes they were cleared for other reasons: the moated site on the W of the wood was made by (men working for) the nuns of Clerkenwell, for a small manorial centre for to manage land nearby, given to them by 1182 british-history.ac.uk/vch/cambs/vol5…. It too has been reabsorbed.

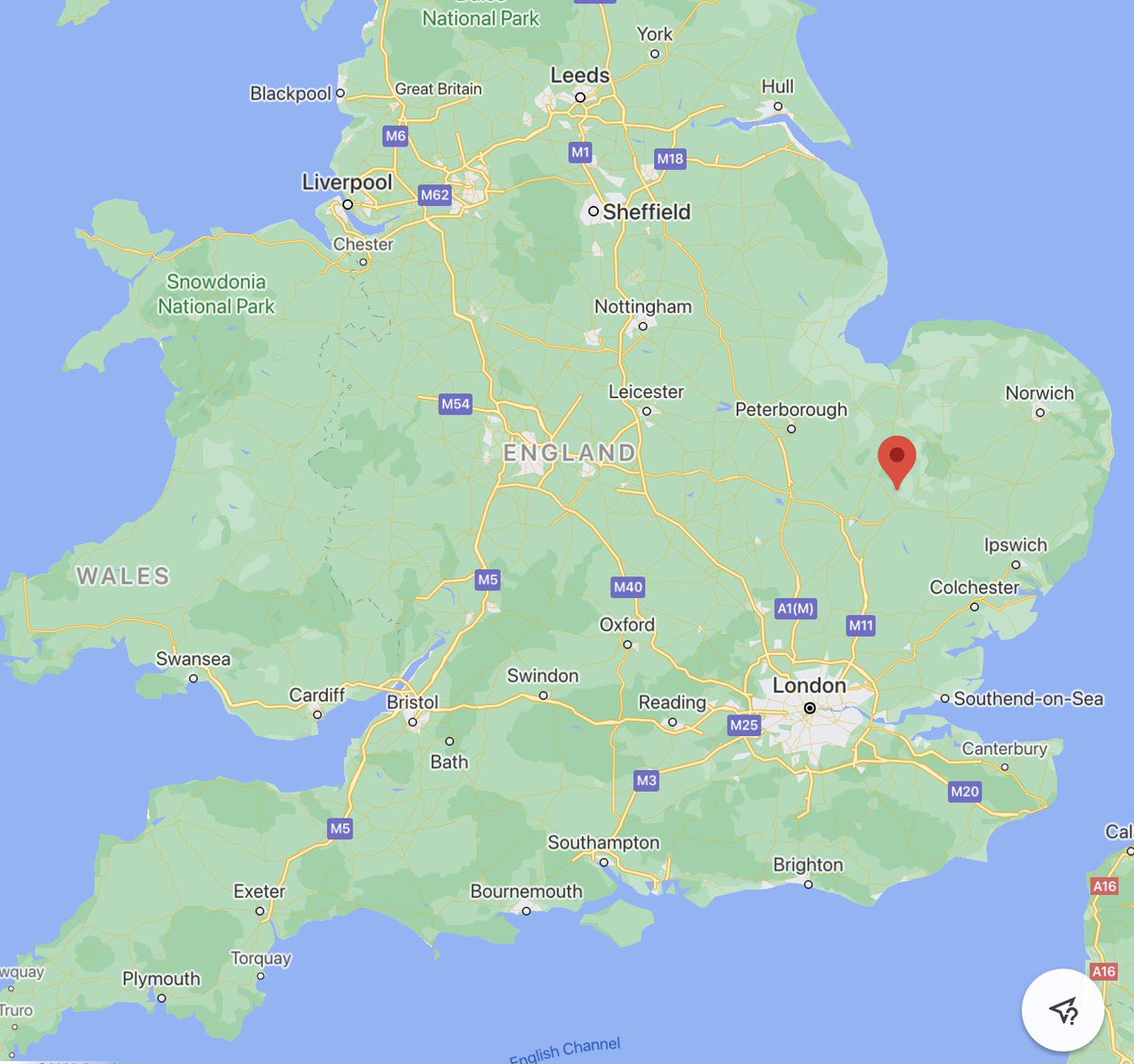

7. Which reminds me that ancient woods often (though not invariably, lie across parish boundaries (the ... dots on the map): Eversden to N and E, Kingston on the SW, and Wimpole to the S.

8. Rackham remarked, too, that many medieval woods tend to be marked by characteristic banks & ditches: a ditch on the outside, & a bank on the inside, originally hedge-topped, to make it difficult for grazing animals to get in. This was because

9. .. such woods were managed to create crops for different purposes: some trees (eg ash, hazel) were coloured (cut to the ground at intervals of 4-8 years to make eg wood for fences, handles for tools; some trees (standards) were allowed to grow tall ..

blog.rowleygallery.co.uk/hayley-wood/

blog.rowleygallery.co.uk/hayley-wood/

10. .. to produce wood for houses; and brushwood was collected for firing ovens and hearths. (Photo: coppicing at Hayley Wood wildlifebcn.org/blog/rob-ender…).

11. Woodland managed for cropping can often be identified in Domesday Book. Eversden wood was managed for fences (and no doubt other purposes) in 1086. The original Latin is useful, too, as it tends to use ‘nemus’ (a grove) for managed woodland and

12. .. ‘silva’ for unmanaged woodland where animals were allowed in, since there were no coppices whose spring leaves they could eat. Most often Domesday Bk mentions pigs like these in the New Forest, allowed to roam in autumn for beechmast etc. (newforestcommoner.co.uk/2014/09/22/pan…)

13. The high plateau on which Eversden Wood gave its name to Wetherley Hundred, one of the ancient subdivisions of Cambs. The Hundred met about a mile away, so I think the wood lay on ‘Wetherley’ = pasture studded with trees & grazed by sheep kept for their wool.

14. Rackham also identified 2 plant species which he said were diagnostic of ancient woodland because they are so slow to colonise areas: dogs mercury (L) and oxlips (R) - & we’re just the right side of the solstice to be able to look forward to seeing these in spring.

15. All this & much more in Rackham’s ‘Trees & Woodland in the British Landscape’ 👇, one of the many books offering straightward clues to landscape history that make a muddy winter walk so much fun for us all. END

PS Apologies: the photographs of dog’s mercury & oxlip are from the Woodland Trust woodlandtrust.org.uk

COPPICED, not coloured, spell-check 🙃

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh