!𐩺𐩣|𐩣𐩥𐩡𐩵|𐩫𐩧𐩯𐩩𐩯|𐩷𐩺𐩨𐩬

For Christmas, let's talk a bit how Christianity spread to South Arabia. And fully in the spirit of the season, this is a story of slavery and mass murder.

For Christmas, let's talk a bit how Christianity spread to South Arabia. And fully in the spirit of the season, this is a story of slavery and mass murder.

Most people who know something about South Arabian history have heard about the martyrs of Najran. In or around 523 CE, the South Arabian ruler Yūsuf ʾAšʿar Yaʾṯar (called Dhū Nuwās by later Muslim authors ) massacred the entire Christian population of Najrān.

Most Muslims connected this event with what the Qur'ān (85:4-7) calls the "Companions of the pit" (ʾaṣḥab al-uḫdūd). The Qur'ānic allusion is rather vague, so other interpretations are also possible. This is discussed in David Cook's article "The Aṣḥab al-Uḫdūd".

So what do we know about South Arabian Christianity?

Well, there are only a few truly "Christian" inscriptions. Monotheism spread to South Arabia around the 4th century CE, but most early inscriptions aren't explicitly Jewish or Christian.

Well, there are only a few truly "Christian" inscriptions. Monotheism spread to South Arabia around the 4th century CE, but most early inscriptions aren't explicitly Jewish or Christian.

References to God in monotheist inscriptions are broad. God is described as:

- Lord of Heaven and Earth = mrʾ smyn w-ʾrḍn

- Lord of the Living and the Dead" = mrʾ ḥyʾn w-mwtn

- Creater of Everything" = ḏ-brʾ klm

And most famously, "The Merciful" = Rḥmnn.

- Lord of Heaven and Earth = mrʾ smyn w-ʾrḍn

- Lord of the Living and the Dead" = mrʾ ḥyʾn w-mwtn

- Creater of Everything" = ḏ-brʾ klm

And most famously, "The Merciful" = Rḥmnn.

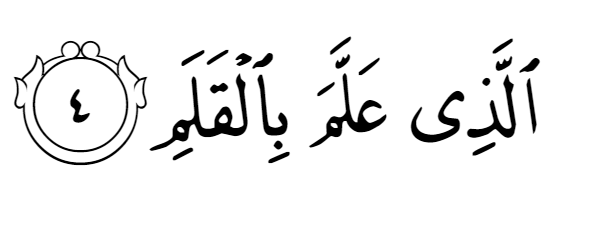

There are explicit references to Christ: one late inscription mentions Christ <krśtś>, whereas three others talk about Raḥmān and His Messiah (rḥmnn w-msḥ-hw).

These inscriptions were made by rulers: one by the Ethiopian puppet Sumyafuʿ ʾAšwaʿ; the others by the king Abraha.

These inscriptions were made by rulers: one by the Ethiopian puppet Sumyafuʿ ʾAšwaʿ; the others by the king Abraha.

But how did Christianity actually spread to South Arabia? The local inscriptions don't really tell us. For this, we have to look outside of the South Arabian inscriptions and towards Christian hagiographies and the later Islamic traditions.

According to the 4th century historian Philostorgius, Christianity first came to South Arabia by one Theophilus the Indian. Philostorgius tells us his mission was successful, although not before adding in a snipe at the Jewish inhabitants of South Arabia.

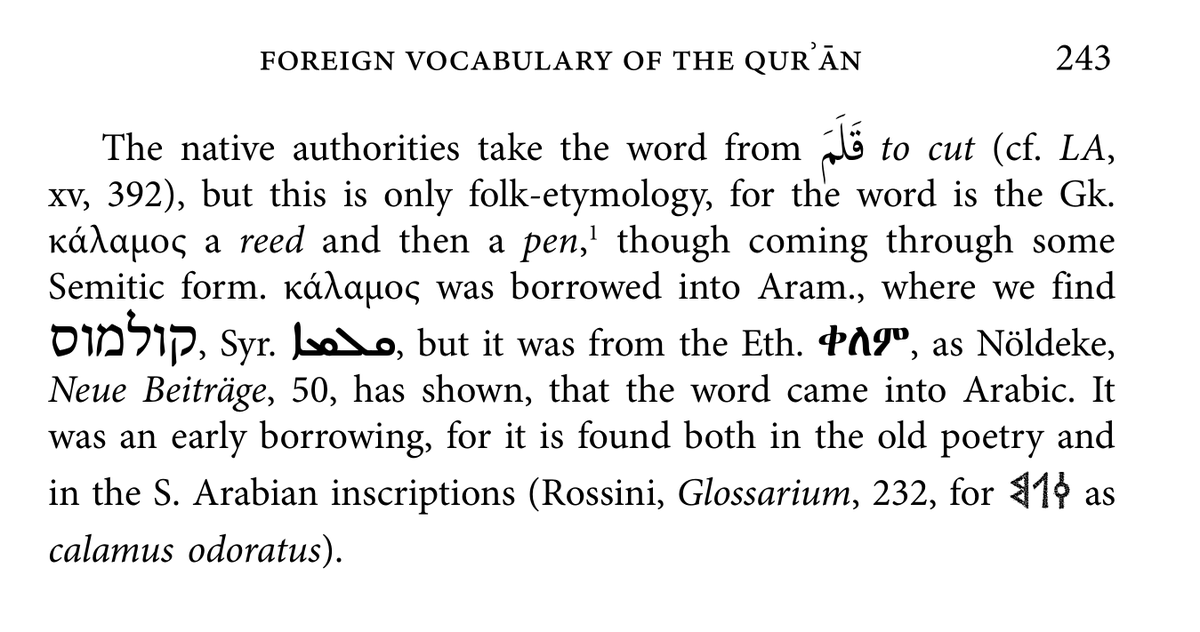

The Islamic tradition tells a different story. According to Ibn Hišām's biography of the Prophet, Christianity came to South Arabia due to a pious Syrian, who also worked as a brickbuilder. His name is transmitted as Faymiyūn (< gr. Phemion) (here in Guillaume's translation).

According to this tradition, Faymiyūn and his loyal sidekick Ṣāliḥ were sold as slaves and ended up in Najrān, the later site of the events of the Pit. Faymiyūn performed a miracle for the local ruler, who was so impressed that he and the local people accepted Christianity.

The Islamic tradition makes it clear Faymiyūn was made a slave by a Bedouin raiding party. There is an interesting parallel with the apocryphal Acts of Thomas.

These Acts tell us Christianity came to India through a carpenter and slave, named Judas Thomas.

These Acts tell us Christianity came to India through a carpenter and slave, named Judas Thomas.

Of course, we know the fate of the Christians of Najrān was less than stellar. According to the near-contemporary Book of the Himyarites, the Christians in the area were slaughtered en-masse by Dhu Nuwās. It's...not pretty.

Was this the end of the South Arabian Christians?

No! Later Muslim authors tell us Muhammad a contract with the Christians of Najran, so some survived the onslaught. Also, we know about a Christian population on Socotra, but this is a topic for a different time! Merry Christmas!

No! Later Muslim authors tell us Muhammad a contract with the Christians of Najran, so some survived the onslaught. Also, we know about a Christian population on Socotra, but this is a topic for a different time! Merry Christmas!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh