THREAD: Some Reflections on the Text of 1 Kings 22.1–39.

TITLE: Why it’s not a good idea to surround yourself with 400 people who agree with you.

#DontBeAnAhab

TITLE: Why it’s not a good idea to surround yourself with 400 people who agree with you.

#DontBeAnAhab

« 22.1–4 »

As we pick up the story in ch. 22, things aren’t what we might expect.

Despite Ahab’s many evils, peace prevails between the northern kingdom (Israel) and her most immediate rival (Syria) (22.1 w. 20.34).

As we pick up the story in ch. 22, things aren’t what we might expect.

Despite Ahab’s many evils, peace prevails between the northern kingdom (Israel) and her most immediate rival (Syria) (22.1 w. 20.34).

And, despite his idolatry, Ahab’s managed to establish closer than usual ties with Judah, courtesy of Jehoshaphat (22.2 w. 44),

who isn’t otherwise a bad king.

who isn’t otherwise a bad king.

As the chapter starts to unfold, the dissonance becomes even more pronounced.

Not long ago, Ahab slew an innocent man (Naboth) in order to acquire a tiny plot of land which didn’t belong to him,

and now in ch. 22 we find out Ahab had all along left Ramoth-Gilead—

Not long ago, Ahab slew an innocent man (Naboth) in order to acquire a tiny plot of land which didn’t belong to him,

and now in ch. 22 we find out Ahab had all along left Ramoth-Gilead—

a major city which *did* belong to him—in the hands of the Syrians.

In 22.4, Ahab therefore asks Jehoshaphat to help him reclaim it,

and Jehoshaphat agrees.

In 22.4, Ahab therefore asks Jehoshaphat to help him reclaim it,

and Jehoshaphat agrees.

« 22.5–6 »

With the advent of 22.5, however, a thought occurs to Jehoshaphat.

‘First let’s seek the word of YHWH’, he says,

which reads rather awkwardly, and deliberately so. Ahab’s already made up his mind to recapture Ramoth-Gilead,

With the advent of 22.5, however, a thought occurs to Jehoshaphat.

‘First let’s seek the word of YHWH’, he says,

which reads rather awkwardly, and deliberately so. Ahab’s already made up his mind to recapture Ramoth-Gilead,

...and Jehoshaphat’s already agreed to help him.

It’s a bit late to seek YHWH’s direction *first*.

Still, Ahab summons 400 of his finest prophets and asks them if he should go up to Ramoth-Gilead.

It’s a bit late to seek YHWH’s direction *first*.

Still, Ahab summons 400 of his finest prophets and asks them if he should go up to Ramoth-Gilead.

In response, they tell him what he wants to hear:

‘Go up, so YHWH may give it into the hand of the king’.

‘Go up, so YHWH may give it into the hand of the king’.

But, although the king is perfectly happy with the prophets’ statement, its syntax is worthy of note insofar as the verb ‘give’ lacks an explicit object (hence the KJV has ‘it’ in italics).

*What* exactly will YHWH give into the hand of the king? And into the hand of which king will he give it?

Ahab assumes the object of the verb ‘give’ is Ramoth-Gilead and the ‘king’ in question is him,

which are natural enough assumptions (grammatically).

Ahab assumes the object of the verb ‘give’ is Ramoth-Gilead and the ‘king’ in question is him,

which are natural enough assumptions (grammatically).

But then things in Israel haven’t panned out very naturally in recent years,

and they won’t pan out how Ahab assumes they will at Ramoth-Gilead either.

and they won’t pan out how Ahab assumes they will at Ramoth-Gilead either.

Also worthy of note is the number of prophets Ahab gathers: 400.

In ch. 18, Elijah does battle with 450 prophets of Baal and 400 prophets of Asherah.

He promptly dispenses with the 450 prophets of Baal, but we’re not told what happens to the 400 Asherahites (18.19 w. 40).

In ch. 18, Elijah does battle with 450 prophets of Baal and 400 prophets of Asherah.

He promptly dispenses with the 450 prophets of Baal, but we’re not told what happens to the 400 Asherahites (18.19 w. 40).

Well, here in ch. 22, we find out: they continue on in Ahab’s service under a different guise.

That’s not to say 22.6’s are the same prophets mentioned in ch. 18. Symbolically, however, they represent the *influence* of those prophets.

That’s not to say 22.6’s are the same prophets mentioned in ch. 18. Symbolically, however, they represent the *influence* of those prophets.

And they represent a particularly dangerous threat to Israel, since they now prophesy in the name of YHWH (cp. 22.11).

To spot a false prophet, it’s no longer enough to look for the guys with spears who leap around on pagan altars.

To spot a false prophet, it’s no longer enough to look for the guys with spears who leap around on pagan altars.

« 22.7–9 »

Despite his readiness to link arms with Ahab, Jehoshaphat isn’t blind.

When a backslidden king with unfulfilled prophecies over his head asks YHWH whether he’ll triumph in battle, the answer ‘Go forth and prosper!’ doesn’t ring true (cp. 20.34–42).

Despite his readiness to link arms with Ahab, Jehoshaphat isn’t blind.

When a backslidden king with unfulfilled prophecies over his head asks YHWH whether he’ll triumph in battle, the answer ‘Go forth and prosper!’ doesn’t ring true (cp. 20.34–42).

And when 400 prophets proclaim it in unison, things start to look even more suspicious.

Jehoshaphat can smell a rat.

He therefore asks if any other prophets are available for consultation,

the answer to which is, ‘Yes, Micaiah!’.

Jehoshaphat can smell a rat.

He therefore asks if any other prophets are available for consultation,

the answer to which is, ‘Yes, Micaiah!’.

So who exactly is Micaiah?

All we know about him is what Ahab tells us: Micaiah is a habitual bearer of bad news.

Nevertheless, Ahab agrees to send for him.

All we know about him is what Ahab tells us: Micaiah is a habitual bearer of bad news.

Nevertheless, Ahab agrees to send for him.

« 22.10–12 »

Meanwhile, the 400 prophets continue with their prophecies,

which become more and more fervent, until a prophet named Zedekiah arises and declares,

‘You will gore the Syrians until they’re completely destroyed!’.

Meanwhile, the 400 prophets continue with their prophecies,

which become more and more fervent, until a prophet named Zedekiah arises and declares,

‘You will gore the Syrians until they’re completely destroyed!’.

As before, the rest of the prophets concur.

They even add an extra imperative to their refrain: ‘Go up and *triumph*!’.

They even add an extra imperative to their refrain: ‘Go up and *triumph*!’.

« 22.13–28 »

Some time later, Micaiah arrives.

Ahab asks him the question he asked the 400 prophets: ‘Should I go up to Ramoth Gilead?’.

To our surprise, Micaiah echoes the words of Ahab’s 400:

‘Go up and triumph!’.

Some time later, Micaiah arrives.

Ahab asks him the question he asked the 400 prophets: ‘Should I go up to Ramoth Gilead?’.

To our surprise, Micaiah echoes the words of Ahab’s 400:

‘Go up and triumph!’.

It’s now, therefore, Ahab’s turn to smell a rat.

Micaiah has never been the bearer of good news before. Why would he start now?

‘No no, tell me the word of *YHWH*!’, Ahab says,

which is a different command to 22.13’s (viz. ‘Let your word be like the prophets’!’),

Micaiah has never been the bearer of good news before. Why would he start now?

‘No no, tell me the word of *YHWH*!’, Ahab says,

which is a different command to 22.13’s (viz. ‘Let your word be like the prophets’!’),

and garners a different response.

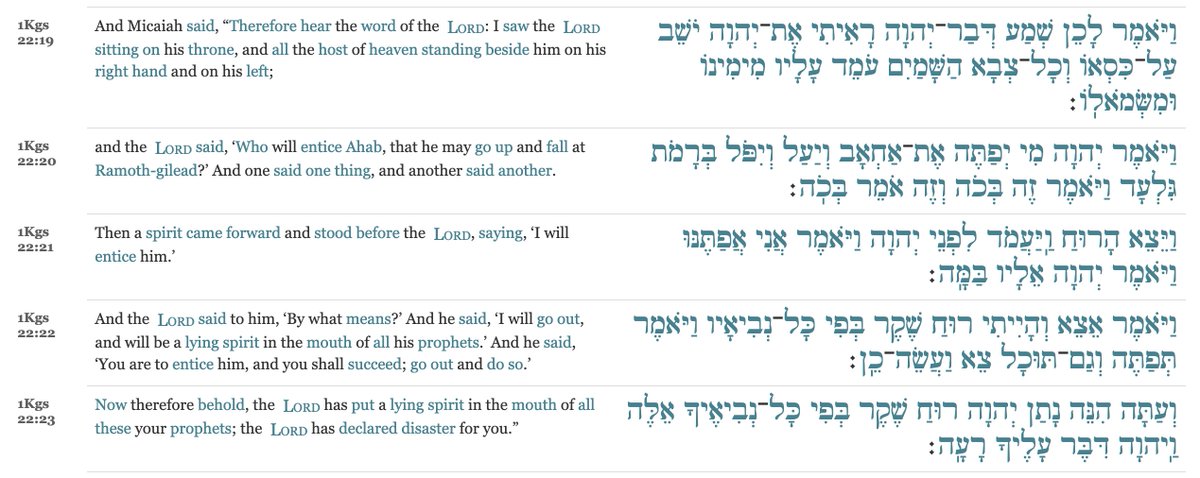

‘I saw all Israel scattered on the mountains, as sheep without a shepherd’, Micaiah begins.

‘…And I saw YHWH seated on his throne, and all the host of heaven stood before him…’

‘I saw all Israel scattered on the mountains, as sheep without a shepherd’, Micaiah begins.

‘…And I saw YHWH seated on his throne, and all the host of heaven stood before him…’

While Ahab took counsel with his prophets in Samaria, Micaiah explains, YHWH took counsel with the hosts of heaven

...and sent a spirit to the earth to put deceptive words in the mouths of Ahab’s prophets.

...and sent a spirit to the earth to put deceptive words in the mouths of Ahab’s prophets.

The claims of Ahab’s prophets are intended to lure Ahab to his death (at Ramoth Gilead),

and they will succeed in their task, Micaiah says.

and they will succeed in their task, Micaiah says.

The text of 22.1–28 thus consists of two panels.

The first describes events on the earth, while the second describes how those events are viewed from the perspective of—and/or have been orchestrated by—heaven.

The first describes events on the earth, while the second describes how those events are viewed from the perspective of—and/or have been orchestrated by—heaven.

« 22.29-39 »

And so, in 22.29, Ahab marches off to his doom.

Ahab isn’t, however, completely unmoved by Micaiah’s words.

He realises his life is in danger.

And so, in 22.29, Ahab marches off to his doom.

Ahab isn’t, however, completely unmoved by Micaiah’s words.

He realises his life is in danger.

But he thinks if he disguises himself as a soldier, he’ll be able to avoid the attention of the Syrians (and escape death).

In a limited sense, Ahab is right. His disguise *does* enable him to avoid the attention of the Syrians.

In a limited sense, Ahab is right. His disguise *does* enable him to avoid the attention of the Syrians.

But it doesn’t enable him to avoid YHWH’s attention.

As the day draws on, a man draws a bow ‘at random’ (lit. ‘in innocence’) and fires an arrow,

which strikes Ahab in the chest (between his armour plates) and kills him.

And Micaiah’s vision is thus fulfilled.

As the day draws on, a man draws a bow ‘at random’ (lit. ‘in innocence’) and fires an arrow,

which strikes Ahab in the chest (between his armour plates) and kills him.

And Micaiah’s vision is thus fulfilled.

Hence, at the close of day’s battle, the Israelites find themselves strewn around the slopes of Ramoth-Gilead, their leader (voluntarily) defrocked and slain,

and each man returns to his own home.

and each man returns to his own home.

REFLECTIONS

The book of Kings mentions a whole slew of battles between Israel and the nations.

The ultimate battle around which it orbs, however, is the battle for truth within Israel itself.

The book of Kings mentions a whole slew of battles between Israel and the nations.

The ultimate battle around which it orbs, however, is the battle for truth within Israel itself.

Even more so than his predecessors, Ahab chooses to surround himself with counterfeit gods and counterfeit prophets.

His life and reign thus raise a question: Can a king of Israel ignore YHWH’s commands and yet prosper?

It seems as they can, for a while.

His life and reign thus raise a question: Can a king of Israel ignore YHWH’s commands and yet prosper?

It seems as they can, for a while.

But, in the end, Ahab, the great deceiver, is deceived. And he is deceived not by another king, but by YHWH himself.

The answer, therefore, to the question ‘Can a king of Israel ignore YHWH’s commands and prosper?’ is ‘No’.

The answer, therefore, to the question ‘Can a king of Israel ignore YHWH’s commands and prosper?’ is ‘No’.

The idea of a God who deceives people, however, raises questions of its own.

Does God *lie* to Ahab in 22.1–39?

Does the God who refers to himself as ‘the God of truth’ assert what is false?

Does God *lie* to Ahab in 22.1–39?

Does the God who refers to himself as ‘the God of truth’ assert what is false?

Not exactly.

By way of illustration, let’s consider who *does* tell lies in ch. 22’s events.

Do the prophets lie to Ahab?

Not in 22.6.

When Ahab asks them if he should go to battle in Ramoth Gilead, they reply with an imperative (‘Go up!’),

By way of illustration, let’s consider who *does* tell lies in ch. 22’s events.

Do the prophets lie to Ahab?

Not in 22.6.

When Ahab asks them if he should go to battle in Ramoth Gilead, they reply with an imperative (‘Go up!’),

which is neither a lie *nor* a statement of the truth; it is merely a command—or perhaps just a piece of bad advice,

since a king can’t properly be said to be *commanded* by his subjects.

since a king can’t properly be said to be *commanded* by his subjects.

True, the purpose clause associated with the prophets’ statement is deceptive (‘Go up so YHWH might give someone/something into the hand of the king!’), since it gives Ahab the impression he’ll triumph in battle.

But it *can* be interpreted in a manner which is consistent with the outcome of ch. 22’s battle,

since YHWH *did* in fact give someone into the hand of a king; he gave Ahab into the hand of the king of Syria.

since YHWH *did* in fact give someone into the hand of a king; he gave Ahab into the hand of the king of Syria.

And, if the prophets’ statement in 22.6 isn’t a lie, then neither is their statement in 22.12 (‘Go and triumph!’).

So what about Micaiah? Does Micaiah lie to Ahab?

Again, not really.

Initially, Micaiah merely does what he’s told. (He’s commanded to echo the words of the 400 prophets, and he does so.)

And, when asked to speak the truth in YHWH’s name, Micaiah again does so:

Again, not really.

Initially, Micaiah merely does what he’s told. (He’s commanded to echo the words of the 400 prophets, and he does so.)

And, when asked to speak the truth in YHWH’s name, Micaiah again does so:

he tells Ahab exactly what he’s seen and heard, and exactly what will happen in the future.

The problem is, Ahab doesn’t believe it. (Jesus’ words in John 8.45 are the words of a prophet: ‘You do not believe me because I tell you the truth!’.)

The problem is, Ahab doesn’t believe it. (Jesus’ words in John 8.45 are the words of a prophet: ‘You do not believe me because I tell you the truth!’.)

What clearly *is* a lie is Zedekiah’s utterance to Ahab in 22.11 (‘You’ll gore the Syrians until they’re destroyed!’).

But the spirit sent forth to deceive (in 22.22) is said to act as a spirit of deception ‘in the mouth of *all* Ahab’s prophets’,

But the spirit sent forth to deceive (in 22.22) is said to act as a spirit of deception ‘in the mouth of *all* Ahab’s prophets’,

which can (perhaps/plausibly) be restricted to those occasions when the prophets speak as one rather than when Zedekiah speaks as a lone agent.

That may, of course, seem a rather fine-grained/tenuous distinction to make,

but the specific flow and detail of ch. 22’s narrative is clearly intended to teach us about the nature of YHWH’s interaction with the world,

but the specific flow and detail of ch. 22’s narrative is clearly intended to teach us about the nature of YHWH’s interaction with the world,

and the fact remains: the prophecy which is most clearly untrue in ch. 22 is the prophecy it is most natural to exclude from the spirit’s influence.

Either way, the text of 22.22 raises yet more questions, most notably, What/who is the ‘spirit’ referred to in 22.22?

And why is it introduced to us as ‘the spirit’ (הרוח)? Have we read about it before?

Rabbi Yochanan suggests the spirit is Naboth (b. Sanhedrin 89a),

And why is it introduced to us as ‘the spirit’ (הרוח)? Have we read about it before?

Rabbi Yochanan suggests the spirit is Naboth (b. Sanhedrin 89a),

which is a provocative idea,

and one with significant exegetical merit, since ch. 22 portrays Ahab’s demise as a case of poetic justice for his slaughter of Naboth:

and one with significant exegetical merit, since ch. 22 portrays Ahab’s demise as a case of poetic justice for his slaughter of Naboth:

🔹 Just as in ch. 21 Ahab convenes an assembly and commissions deceptive men to testify against Naboth, so in ch. 22 YHWH convenes an assembly and commissions a deceptive spirit to lure Ahab to his death.

(In both cases, the deceivers-to-be come forward of their own accord: cp. 21.10’s causative הֹשִיבוּ w. 21.13’s non-causative יֵשְׁבוּ.)

🔹 Just as in ch. 21 Ahab is incited to murder by a ‘spirit of sullenness’ (רוח סרה), so in ch. 22 Ahab is incited to go to battle (and die) by a ‘spirit of deceit’ (רוח שקר).

🔹 Just as in ch. 21 Ahab sheds the blood of an innocent man, so in ch. 22 Ahab’s blood is shed by an arrow aimed ‘in innocence’ (cp. 22.34).

🔹 And, just as dogs lick up Naboth’s blood, so too dogs lick up Ahab’s.

🔹 And, just as dogs lick up Naboth’s blood, so too dogs lick up Ahab’s.

That the spirit mentioned in ch. 22 is Naboth is the spirit of Naboth—or at least a spirit assigned to represent his interests before YHWH’s throne—is, therefore, an attractive notion.

Either way, the result is the same: YHWH gets his man.

Either way, the result is the same: YHWH gets his man.

Ahab tries to worship both YHWH and idols, to deceive YHWH’s people, and to cheat his divinely-appointed death. Yet, in the end, YHWH gets the better of him.

YHWH does not need to *lie* to deceive Ahab, but deceive him he does.

God is not mocked.

YHWH does not need to *lie* to deceive Ahab, but deceive him he does.

God is not mocked.

Of course, the idea of YHWH as a deceiver is not a comfortable one.

Should we be nervous about our interaction with such a God? Should we feel anxious about his trustworthiness?

No. But then nor should we trifle with him.

Should we be nervous about our interaction with such a God? Should we feel anxious about his trustworthiness?

No. But then nor should we trifle with him.

And we should regularly challenge our hearts to make sure we genuinely want to know God’s truth.

Ahab didn’t want to believe God’s truth.

He preferred to surround himself with yes-men who told him what he wanted to hear.

Ahab didn’t want to believe God’s truth.

He preferred to surround himself with yes-men who told him what he wanted to hear.

And, in the end, Ahab found he *couldn’t* believe God’s truth.

His life thus serves as a cautionary tale.

In today’s world, it’s incredibly easy to play Ahab’s game:

to find ourselves 400 ‘experts’ on Twitter who all sing from the same hymn sheet and follow only them,

His life thus serves as a cautionary tale.

In today’s world, it’s incredibly easy to play Ahab’s game:

to find ourselves 400 ‘experts’ on Twitter who all sing from the same hymn sheet and follow only them,

to restrict our interaction with (and respect for) people to those who agree with us,

and so on.

and so on.

If we *want* to believe a particular claim, a few hours’ worth of one-sided ‘investigation’ on the internet is all it takes. (People who say we can’t choose what we believe are mistaken.)

Of course, no-one *thinks* they investigate issues in such a manner,

but most people do,

which is why we have God’s word to remind us not to do so with the help of cautionary tales like Ahab’s.

THE END.

Please share/re-tweet if you’ve found these thoughts helpful.

but most people do,

which is why we have God’s word to remind us not to do so with the help of cautionary tales like Ahab’s.

THE END.

Please share/re-tweet if you’ve found these thoughts helpful.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh