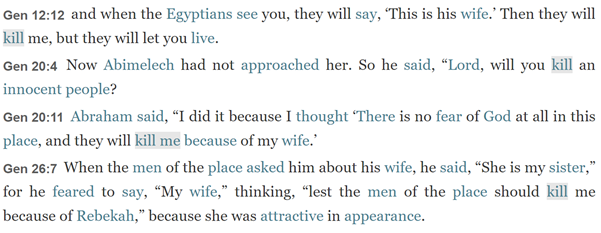

THREAD: Why do English Bible translations often have different poetic stanzas? (inspired by @JennGuenther)

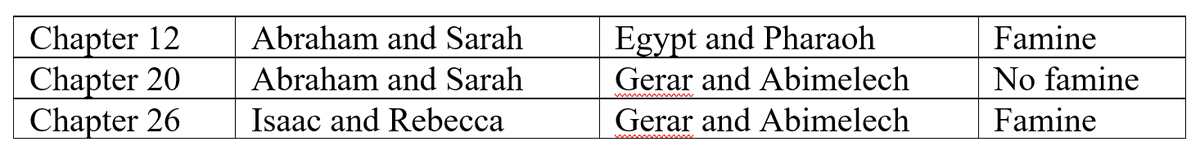

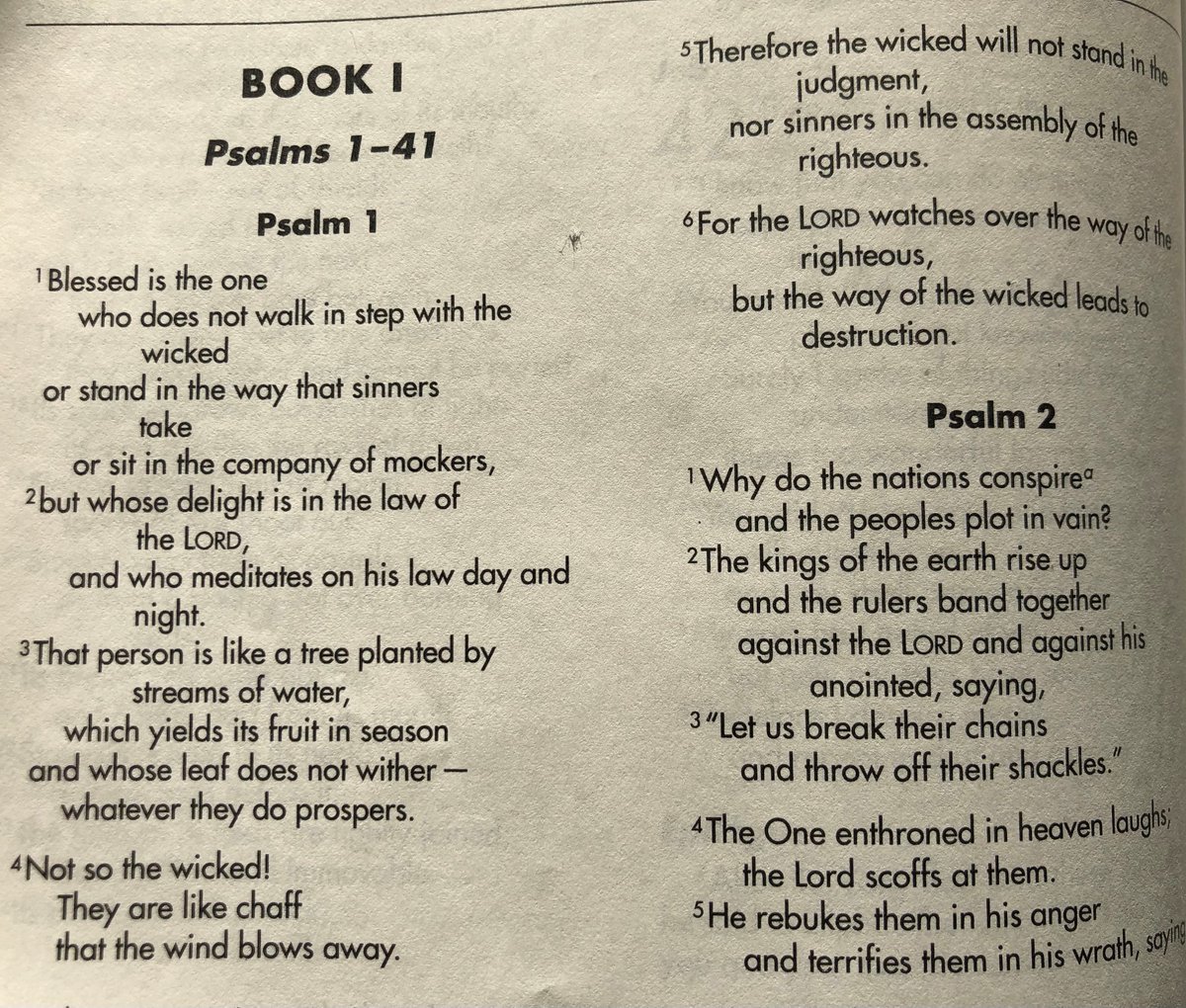

Psalm 1 is divided by the NIV into verses 1-3, 4-5, & 6, but by the ESV into 1-2, 3-4, & 5-6.

Psalm 1 is divided by the NIV into verses 1-3, 4-5, & 6, but by the ESV into 1-2, 3-4, & 5-6.

Whichever of these is better (or neither), it’s worth knowing that translations usually aren’t following ancient manuscripts.

There are some ancient paragraph divisions in Hebrew manuscripts (look up petucha פְּתוּחָה ‘open’ and stuma סְתוּמָה ‘closed’ paragraphs).

There are some ancient paragraph divisions in Hebrew manuscripts (look up petucha פְּתוּחָה ‘open’ and stuma סְתוּמָה ‘closed’ paragraphs).

But we still await the #GreatParagraphReform when, some time in the 21st century, modern Bible translations are revised to follow ancient manuscript paragraphs.

In Psalms ancient stanzas may also be indicated by a musical term like selah or by a clear structure, such as when Psalm 119 is made up of 176 verses, in groups of 8, each beginning with successive letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

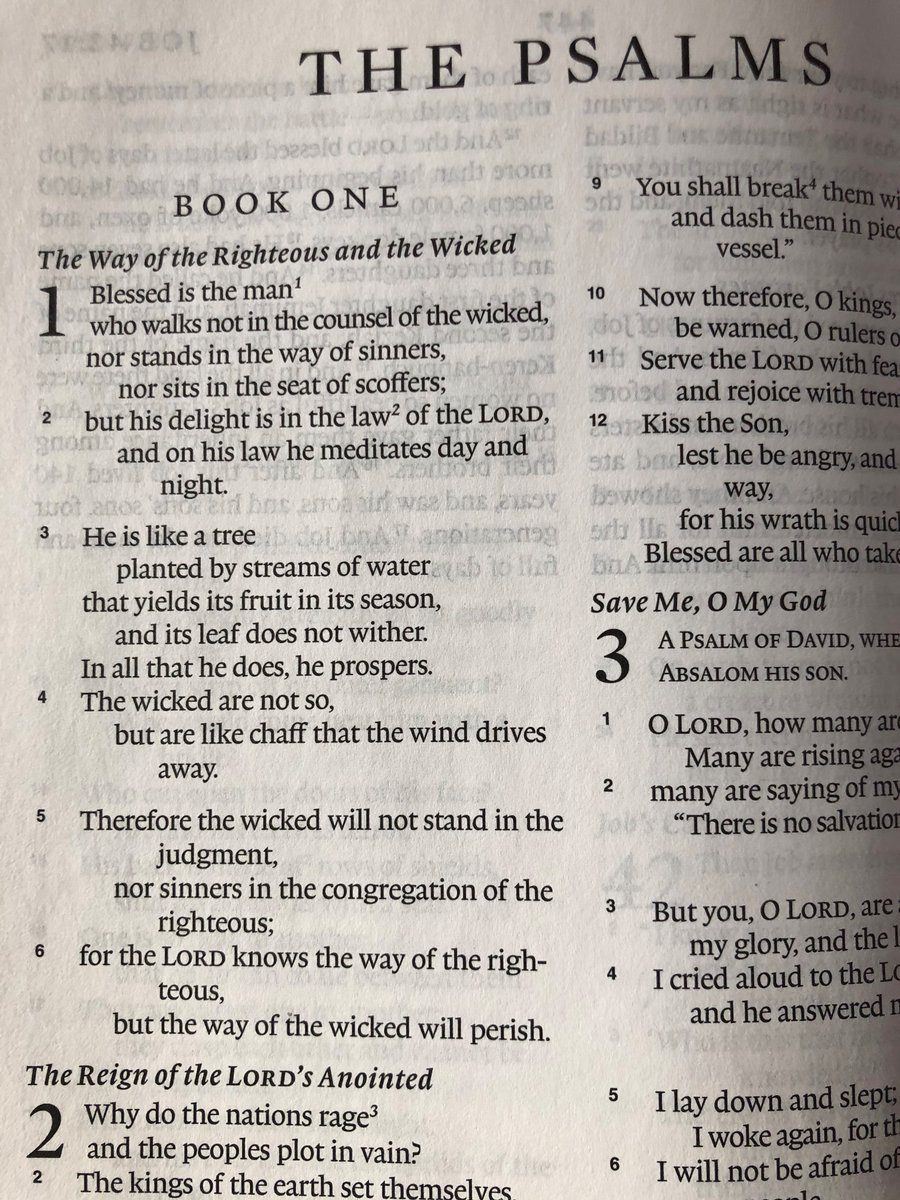

Now for early manuscripts of Psalm 1:

The most important is the beautiful #AleppoCodex (10th century). The scribe always ensures that verses (= modern verses) begins a new line (lines 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8). However, mid-line spaces, don’t correspond with our ideas of poetic breaks.

The most important is the beautiful #AleppoCodex (10th century). The scribe always ensures that verses (= modern verses) begins a new line (lines 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8). However, mid-line spaces, don’t correspond with our ideas of poetic breaks.

The principle is that the Hebrew is both right and left justified. Any line with sufficient space also gets a break in the middle.

Unlike modern English translations, there are no extra vertical spaces between lines.

Unlike modern English translations, there are no extra vertical spaces between lines.

The #LeningradCodex (AD 1008) is the earliest complete copy of the Hebrew Old Testament, but is neither so fair, nor so well made as the #AleppoCodex. Verses and physical line beginnings don’t align.

Also, there are no spaces marking stanzas.

Also, there are no spaces marking stanzas.

Next up the beautiful Greek #CodexVaticanus (4th century).

Material within long poetic lines is left hanging (indented).

New verses (= modern verses) always begin new lines.

But there are no vertical spaces between lines or verses.

Material within long poetic lines is left hanging (indented).

New verses (= modern verses) always begin new lines.

But there are no vertical spaces between lines or verses.

#CodexAlexandrinus (5th century) is harder to read, but basically tells a similar story to #CodexVaticanus, though hanging is less pronounced.

#CodexAmiatinus, the greatest of all Latin Bible manuscripts

therefore naturally from the North of England, the usual location of the best Bible scholarship (

shows no spaces between lines and is similar to the Greek manuscripts.

therefore naturally from the North of England, the usual location of the best Bible scholarship (

https://twitter.com/DrPJWilliams/status/1069014292257742849?s=20)

shows no spaces between lines and is similar to the Greek manuscripts.

So though it’s possible that stanzas you see in an English Bible have some justification in manuscripts, it’s usually best to assume they don’t.

Moreover, even if the original poets thought in terms of stanzas, they probably didn’t mark spaces between them.

Moreover, even if the original poets thought in terms of stanzas, they probably didn’t mark spaces between them.

In Ugarit, near Israel, in the 13th-12th centuries BC, they wrote poetry with parallelism of poetic lines just as Hebrew Psalms, but didn’t feel the need to start new poetic lines on new physical lines.

We’ve little direct evidence to think that Hebrews normally sang in stanzas.

We’ve little direct evidence to think that Hebrews normally sang in stanzas.

I write a little bit more about the history of verse divisions (including a time when Psalm 1 was divided into 7, not 6, verses) here: tyndalehouse.com/magazine/read/1

@K_L_Phillips has much to say about how Hebrew manuscripts laid out poetry:

https://twitter.com/K_L_Phillips/status/1329104251059105796?s=20

Conclusion

In Psalms, division into poetic lines is generally old.

Division into poetic stanzas generally is not.

It’s good to start by assuming close connections may be found across a whole Psalm, not just between nearby lines.

In Psalms, division into poetic lines is generally old.

Division into poetic stanzas generally is not.

It’s good to start by assuming close connections may be found across a whole Psalm, not just between nearby lines.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh