1/ As I have mentioned, the story of #IranChina relations is not always a story of economic exchange and social integration. The lives of the elite were one thing, but this thread will look at the history of Persian slaves, merchants, and pirates in China. - by @IranChinaGuy

2/ Feng Ruofang is known to historians as a pirate who once made his base at Hainan, an island off the southern tip of China. In 742, a shipwrecked monk attested to his activities. Feng "seized two or three Persian merchant ships every year, taking the cargo for himself and...

3/ ...making the crew his servants. They were kept in an area three days’ journey going from north to south and five days’ journey going from east to west, where villages eventually developed."

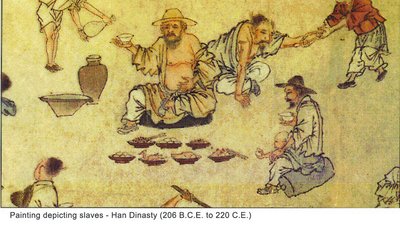

Slavery in China, like in much of the ancient world, was not chattel slavery, but...

Slavery in China, like in much of the ancient world, was not chattel slavery, but...

4/ a kind of subservient social class with malleable borders. Hence, it was not uncommon for slaves and their descendants to live in their own villages. However, the lives of slaves could be incredibly brutal and harsh. See my thread on Chinese slavery:

https://twitter.com/IranChinaGuy/status/1330924112039059464?s=20

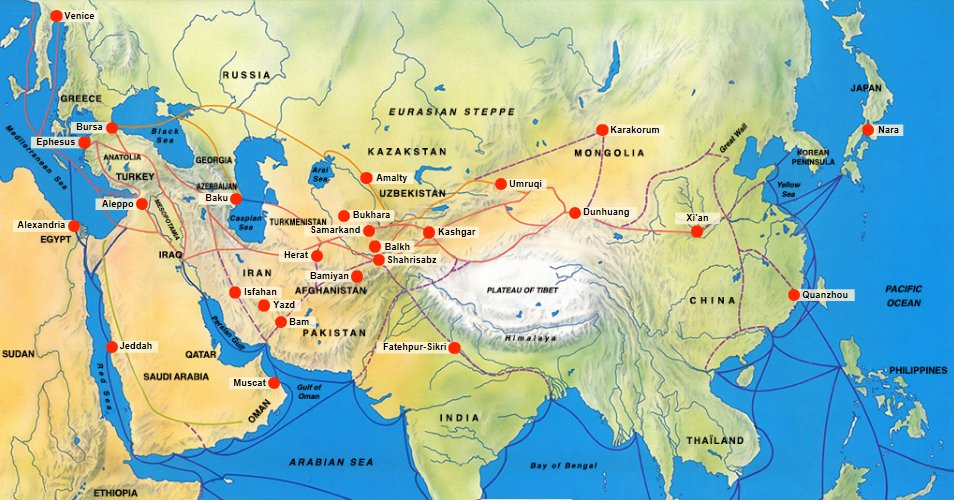

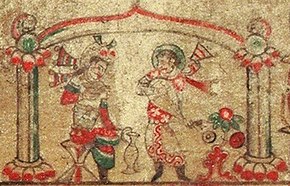

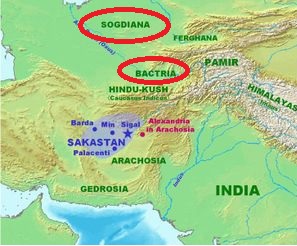

5/ Persian slaves had been a desired commodity in China since ancient times, usually women. Tomb records show Sogdian slave girls were sold for five times the price of silk. In fact, slave girls were one of the major commodities traded by the Sogdians on the early Silk Road.

6/ One reason Persians and Arabs were often taken prisoner was that they were a tempting target, due to their commercial activity. These images show items recovered from a 9th century Arab shipwreck near China, showing the type of items that were traded, and a model ship.

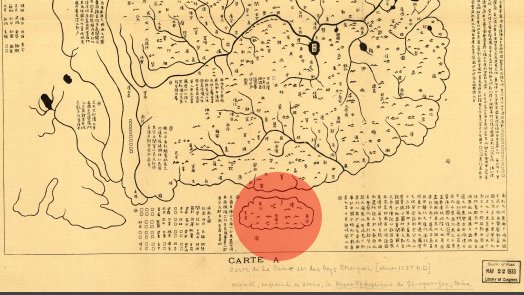

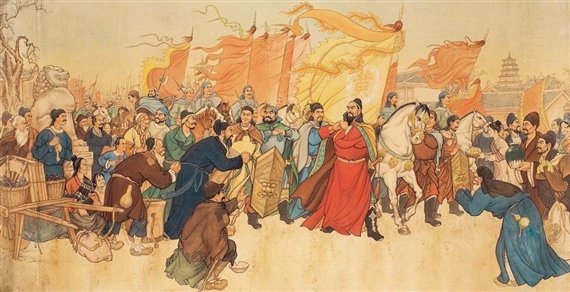

7/ "Fabulously rich" Persian merchants could be found throughout Canton, at the critical trade city of Yangzhou, and in the capital of Chang'an. The famous Arab traveler Ibn Battuta attested to their status in 1346, when he visited Hangzhou, Quanzhou, Guangzhou, and other cities.

8/ Battuta describes several prominent Persians living in Quan-zhou: Kamāl-al-Dīn ʿAbd-Allāh Eṣfahānī, a religious leader; Tāj-al-Dīn Ardabīlī, a Muslim judge; the prosperous merchant Šaraf-al-Dīn Tabrīzī; and Borhān-al-Dīn Kāzerūnī, a shaikh of the Kāzarūnīya order of Sufis.

9/ In addition to these more lawful professions, whether for their own benefit or as slaves of others, Arabs and Persians sailed the coasts of southern China as pirates as well as prey. They often raided southern Chinese ports, which could bring reprisals on the whole community.

10/ For example, in 760 CE, thousands of Persian and Arab merchants were massacred in Yangzhou, in part as a reprisal for the An Lushan rebellion (you may recall An was of Persian lineage) and for an especially devastating pirate attack during the unrest.

11/ A hundred years later in 878, in Guangzhou, tens of thousands of Persians and Arabs (among other foreigners) were massacred by the rebel Huang Chao when they sacked the city. Arab sources claim this ended the presence of Muslims, Christians, and Jews in the city permanently.

12/ Events like this often strained intercommunal relations on the day-to-day level, feelings which only intensified after the fall of the Mongol-controlled Yuan Dynasty, which ushered in a wave of nativist, anti-foreign sentiment under the Ming.

13/ Fifty years before the massacre, in Guangzhou, the local government ordered Arabs and Persians to live in a separate quarter and forbid intermarriage between Chinese and "southern barbarians". The foreigners were allowed to keep their religion and remain in the city, but...

14/ ...incidents like this highlight how intercommunal relations could often be strained. The biography of Lin Nu, a Ming merchant and scholar, attests how his uncle disowned him after he was "seduced" by a "strange and exotic" Persian girl from Hormuz.

15/ In our upcoming threads, we will explore...

- Chinese ceramics and the influence of Chinese art on Iran

- Iranian religions in China

- Sino-Iranian relations during the Mongol era...

- ...and during the Safavid era

Hope to post a lot tomorrow! - B.F @IranChinaGuy

- Chinese ceramics and the influence of Chinese art on Iran

- Iranian religions in China

- Sino-Iranian relations during the Mongol era...

- ...and during the Safavid era

Hope to post a lot tomorrow! - B.F @IranChinaGuy

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh