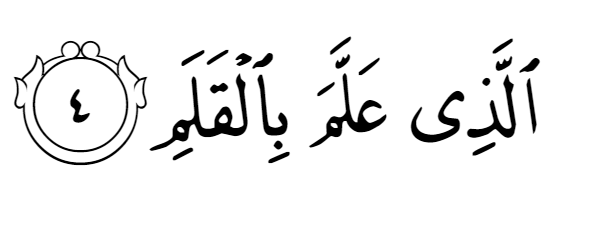

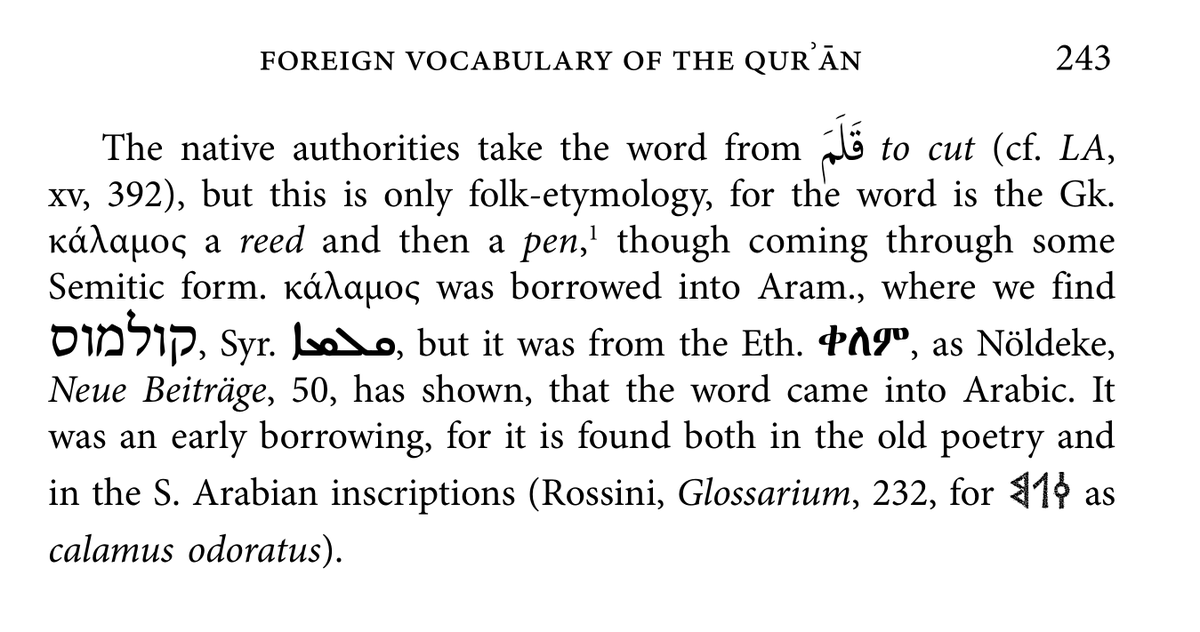

Last week I tweeted this. One of the comments argued that the origin of Arabic qamīṣ < Latin camisia is hypothetical. It reminds me of people sometimes say "well [proven thing] is just a *theory*".

A thread on methods in historical linguistics.

bit.ly/3iXqTTf

A thread on methods in historical linguistics.

bit.ly/3iXqTTf

The further one goes back in history, the more difficult it becomes to find direct evidence for how a word was pronounced or where it came from. Many cultures, but certainly not all, invented writing systems, making our job somewhat easier, but certainly not always.

So what kind of methods can we use to figure out where a word came from.

Firstly: phonology. As a language changes, so does pronunciation. Certain sound changes are much more common than others. For example, /k/ > /t͡ʃ/ is much more common than //t͡ʃ/> k.

Firstly: phonology. As a language changes, so does pronunciation. Certain sound changes are much more common than others. For example, /k/ > /t͡ʃ/ is much more common than //t͡ʃ/> k.

So in the Germanic languages, we find the word for "church" has both /tʃ/ and k. Based on phonological principles, we assume that the forms with /k/ are probably closer to the original word, whereas forms with /tʃ/ are probably more innovative.

In this case we *know* we're right, because the (West-)Germanic word for church actually goes back to Greek kuriakon.

But what if we didn't know the origins of the word "church"? We can still use phonological principles to determine the most likely original form. Often, such a word is not directly attested, because people didn't or couldn't write it down, so we put an asterisk before it.

This type of sound change I mentioned is called lenition; i.e. a sound becomes "weaker" (i.e. /tʃ/ is a "weaker" sound than /k/). The opposite of lenition is fortition, although this is comparatively much rarer. There are many such sound changes, conveniently available on Wiki.

A principle in historical linguistics is that diachronic sound changes (meaning over time) are regular and occur without exception. This was famously formulated by the Neogrammarians.

But then how about English yard/garden, which have the same origin? Let's talk about loanwords.

But then how about English yard/garden, which have the same origin? Let's talk about loanwords.

Obviously, people do not come up with words for things they don't know. A lot of modern langs borrowed the word "computer" from English. Sometimes, institutions whose intend to "maintain linguistic purity" can come up with artificial new words (neologisms), but this

As you can imagine, borrowing is a very old process. For as long as we have evidence for written language, there are indications for loanwords.

For example, in Sumerian and Egyptian (some of the earliest attested languages) there is evidence for non-native words.

For example, in Sumerian and Egyptian (some of the earliest attested languages) there is evidence for non-native words.

But wait, one might ask, how do we know a word is borrowed? Well, f you look at a word but can't break it into constituent elements, it's probably borrowed. E.g. English aardvark cannot be broken down further; but in the donor language Afrikaans it means earth (aard) pig (vark).

Another good idea is to look whether the word occurs in (closely-)related languages. If not, then it's probably a loanword. E.g. Estonian "tudeng" does not appear in any of its related Finno-Ugric languages, but is obviously similar to High German "Student".

In such situations, knowledge of historical contact between speakers of various languages comes in very handy. Estonia's first universities were staffed and attended by German-speakers. Knowing this, we can logically assume the word came from German (of course, eventually Latin)

The further in history you go, the more difficult and controversial this debate becomes. Especially in the ancient Mediterranean there are words whose origins are extremely difficult to pinpoint, because they appear all over the place and our usual methods don't work well.

Take the word for "wine". We get this in Latin as vīnum, Greek (w)oinos, Hebrew yayin, Arabic wayn, Ancient South Arabian wyn and Ethiopic wäyn. Where did this word originally come from? I don't know, but historical linguists love to argue about such words.

Thes so-called Wanderwörter ("travelling words") aside, it is really worth pointing out that historical linguistics is not just a matter of finding two similar looking or sounding words and come up with a reason why they are related.

There are people, of course, who really like to do this: the Arabic professor Zaidan Ali Jassem likes to come up with reasons why apparently all languages come from Arabic, and there's this guy obsessed with proving Venetic is a Finno-Ugric language, for some reason.

The majority of such pseudo-linguistic theories are harmless (although historically they can have devastating impacts, esp. if they inform official linguistic policy), but they serve as a good example as to how falsification in historical linguistics work:

To explain the origins of a word, any theory should be able to answer these questions:

1. Are the proposed sound changes regular or not?

2. Can we find (traces of) this word in related languages.

3. Is there non-linguistic evidence to support contact?

1. Are the proposed sound changes regular or not?

2. Can we find (traces of) this word in related languages.

3. Is there non-linguistic evidence to support contact?

This thread ran much longer than I thought, but I it seems useful to show both historical linguistic principles as well as explain why pseudo-linguistic theories often don't work.

I'm sure other linguists could add a lot to what I wrote here: consider it an invitation

THE END

I'm sure other linguists could add a lot to what I wrote here: consider it an invitation

THE END

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh