All sophisticated solutions start extremely simple

(a thread on this mental model)

📕 It's also 10th chapter of my book invertedpassion.com/all-sophistica…

(a thread on this mental model)

📕 It's also 10th chapter of my book invertedpassion.com/all-sophistica…

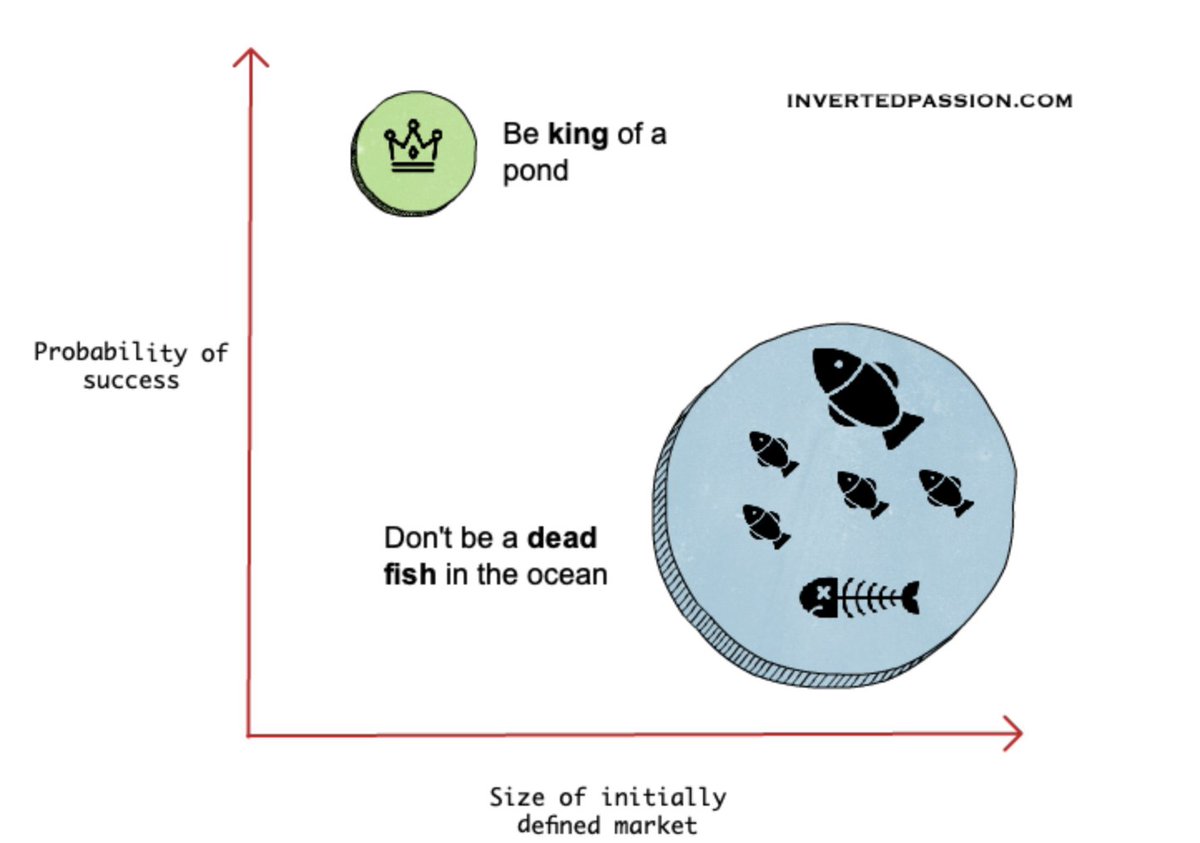

1/ There’s always a temptation to launch a fully built product with more features and capabilities than existing competitors.

It’s exciting to build the next Google, the next iPhone or the next SpaceX, isn’t it?

It’s exciting to build the next Google, the next iPhone or the next SpaceX, isn’t it?

2/ This temptation is dangerous because even the most successful products in a market had simple beginnings.

No product arrives in the market fully fleshed out.

No product arrives in the market fully fleshed out.

3/ The company behind a successful product has developed its internal capabilities and know-how about various tiny but important details over a long period of time.

On day 1, a startup simply cannot match such capabilities.

On day 1, a startup simply cannot match such capabilities.

4/ Think of your favorite products – from the phone you use to the car you drive.

The first version of such products was extremely simple.

It’s only after thousands of incremental advances that today these market-dominating products appear so marvelously sophisticated.

The first version of such products was extremely simple.

It’s only after thousands of incremental advances that today these market-dominating products appear so marvelously sophisticated.

5/ Does it then mean that it’s impossible to compete in an existing market?

Yes, it’s impossible to beat existing players if the aim is to compete with them head-on.

Yes, it’s impossible to beat existing players if the aim is to compete with them head-on.

6/ Mature markets require mature products and getting there takes time.

If you make an attempt to build a sophisticated product in the first go itself, chances are that you will miss many subtle but important details behind existing leading products’ dominance in the market.

If you make an attempt to build a sophisticated product in the first go itself, chances are that you will miss many subtle but important details behind existing leading products’ dominance in the market.

7/ There’s also a risk of massive time and cost overruns during the development of a complex product.

And after launch, because the product wasn’t iterated in the market, early users are likely to get confused by the strangeness of design.

And after launch, because the product wasn’t iterated in the market, early users are likely to get confused by the strangeness of design.

8/ Even if you get early adopters, all the feedback on the product – a million tiny nuisances and misses – is likely to overwhelm your team.

In short, aiming for a fully built out product on day 1 is a recipe for disaster.

In short, aiming for a fully built out product on day 1 is a recipe for disaster.

9/ The most famous example of such a disaster is perhaps Apple’s first personal computer Lisa. Its development started in 1978. Steve Jobs wanted it to be perfect before launch, so the launch was delayed multiple times. It finally launched in 1983 with a hefty price tag of $10k.

10/ Lisa was costly because Apple introduced multiple innovations on day 1 with it – new OS, new GUI interface, a new file system, and floppy disks.

The combination of these innovations translated into a sub-par experience for customers.

The combination of these innovations translated into a sub-par experience for customers.

11/ It was too strange for customers. People like novelty but not too much of it.

Hence, selling only 10,000 units, Lisa became Apple’s biggest failure, nearly bankrupting them.

If entrepreneurs shouldn’t aim to build a fully built-out product, what should they aim for?

Hence, selling only 10,000 units, Lisa became Apple’s biggest failure, nearly bankrupting them.

If entrepreneurs shouldn’t aim to build a fully built-out product, what should they aim for?

12/ A much wiser choice is to start with a simple product that excels only on one (or a few) aspects that customers care about, that existing competitors aren’t providing.

The rest of the product features should be non-existent or extremely basic.

The rest of the product features should be non-existent or extremely basic.

13/ Take @elonmusk's strategy with Tesla for example.

It may seem that in 2004 when they started, the car market was already mature.

But they didn’t set out to build a general-purpose car. Their first car, Roadster, was a sports car meant for a niche audience.

It may seem that in 2004 when they started, the car market was already mature.

But they didn’t set out to build a general-purpose car. Their first car, Roadster, was a sports car meant for a niche audience.

14/ Their strategy was to gain experience in building a car for a very specific customer – the one who desired electric sports cars before attempting to challenge the automotive industry giants.

15/ Even with that limited ambition, Tesla didn’t initially build the technology in-house.

They took technical help from a company called AC Propulsion and car manufacturing help from Lotus, a company with seven decades of experience in building cars.

They took technical help from a company called AC Propulsion and car manufacturing help from Lotus, a company with seven decades of experience in building cars.

16/ Even after all the help, it took Tesla four years – from 2004 to 2008 – and multiple prototypes to launch the first version of the Roadster.

The Tesla cars that we see today are a result of a very simple first version evolving over a period of time.

The Tesla cars that we see today are a result of a very simple first version evolving over a period of time.

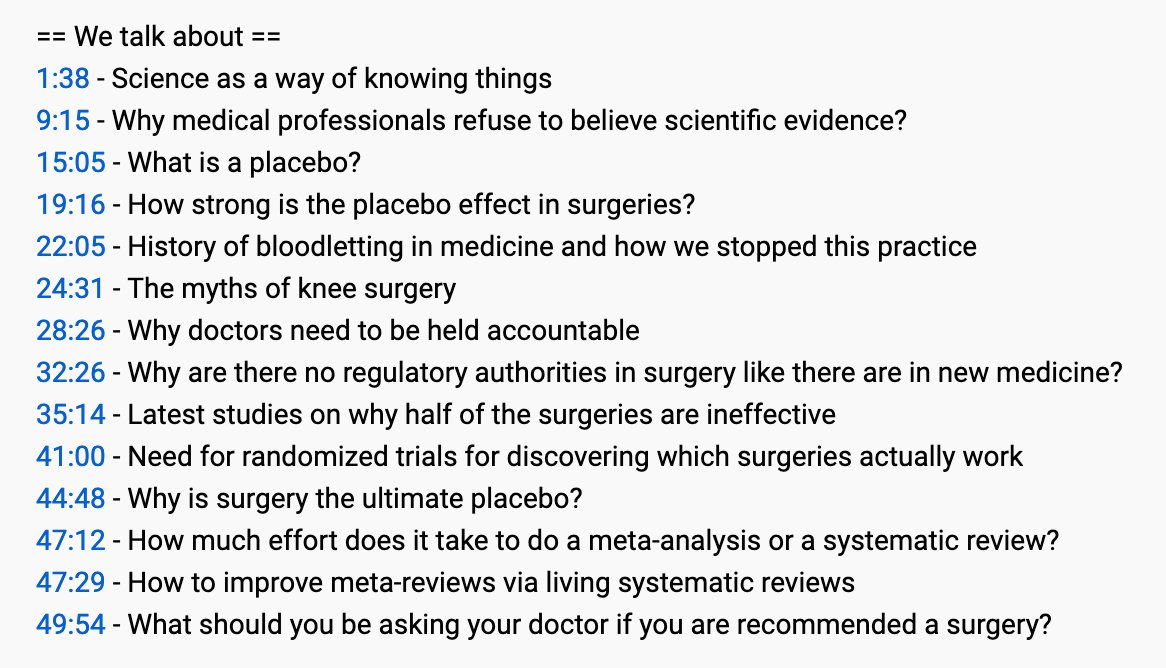

17/ All big companies ignore niches and building an extremely focused product for that niche is a much better strategy than trying to compete with the entire market.

18/ When starting out, aim to be the king of a pond, not a dead fish in the ocean. Once you dominate your pond, you can always aim to dominate another, and much bigger, pond.

invertedpassion.com/define-your-ma…

invertedpassion.com/define-your-ma…

19/ 🧠 Remember:

initially, do one thing but do it really well and ignore everything else.

initially, do one thing but do it really well and ignore everything else.

21/ I'm posting ~1 new mental model for entrepreneurs every week.

I just posted the 10th one.

Here's the entire list of 60+ mental models that I'll cover in a year or so: invertedpassion.com/free-book-ment…

Make sure you sign up for email updates on the book page.

I just posted the 10th one.

Here's the entire list of 60+ mental models that I'll cover in a year or so: invertedpassion.com/free-book-ment…

Make sure you sign up for email updates on the book page.

22/ Check out the previous mental model thread here:

https://twitter.com/paraschopra/status/1353967546987409408

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh