Clinical trials are in the public eye once again, and Vitamin D for COVID is especially topical right now. Like everything in healthcare, the trials are complex, so here’s an explainer on them. These points are most important for doctors but relevant to us all. 1/15

One particular trial provoked debate this week. Enthusiasts insist it proves the role of Vitamin D in treating COVID but experts highlight numerous problems with how the research was done. These limitations mean the research should not, on its own, change patient care… 2/15

…because we need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of a trial to safely use the results to shape patient care. When non-experts get involved we have problems. Some doctors make these mistakes too I’m afraid. 3/15

https://twitter.com/GidMK/status/1361063430745022467?s=20

The best evidence comes from randomised trials where we allocate patients to treatment A or B at random. This avoids doctors guessing about who may benefit the most and who may get the worst side-effects. Our guessing often results in very misleading data! 4/15

Small (10s-100s) ‘efficacy’ trials test treatments in ideal circumstances. But real-world healthcare is never ideal so we also need large (100s-1000s) ‘effectiveness’ trials to allow for this. Efficacy trials answer ‘can it work?' Effectiveness trials answer ‘does it work?’ 5/15

Efficacy trials limit which patients take the treatment, and control how its delivered. Effectiveness trials are more like normal healthcare. Treatments are simplified to make them easy to deliver correctly, and given to any patient who may benefit, not just the best fit. 6/15

It's common to find that treatments show promise in small efficacy trials but don’t work well enough in large effectiveness trials. This doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t work at all rather that the real-world benefits may be marginal or too small to justify the treatment. 7/15

We might think that even a small benefit is worth having, but this ignores the downsides that every treatment has. Whether it’s treatment harm (every drug has side-effects) or just making patient care more complicated, the downsides of a treatment often outweigh the upsides. 8/15

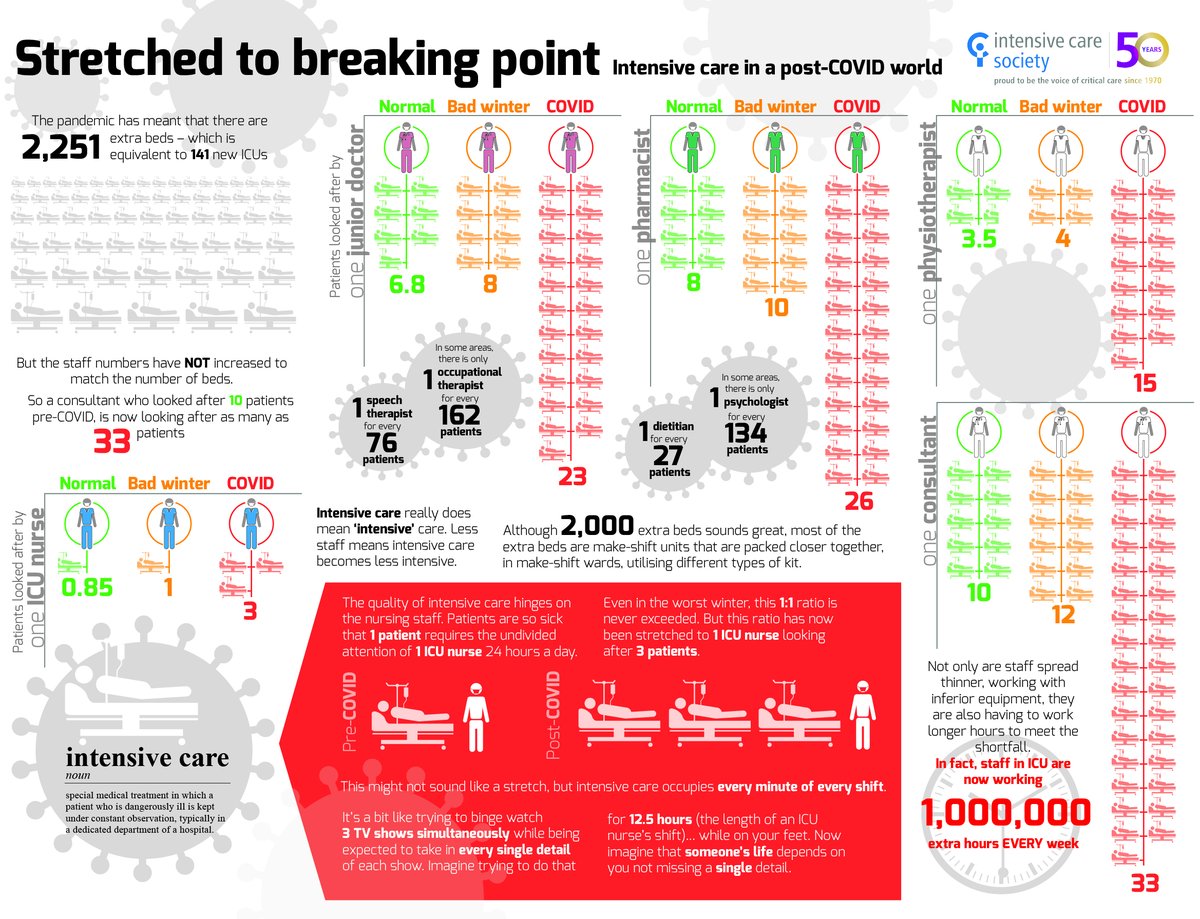

In my early days as an ICU doctor, we tried all sorts of treatments, thinking even a small benefit was worth taking. But one by one we found many of our treatments caused harm which we couldn’t see. We know this because we did large effectiveness trials. 9/15

When there isn’t a clinical trial to tell us how to use a treatment, we study it in routine patient care to see how well it works. But these ‘observational’ studies are often misleading because the results are strongly influenced by what doctors expect to happen. 10/15

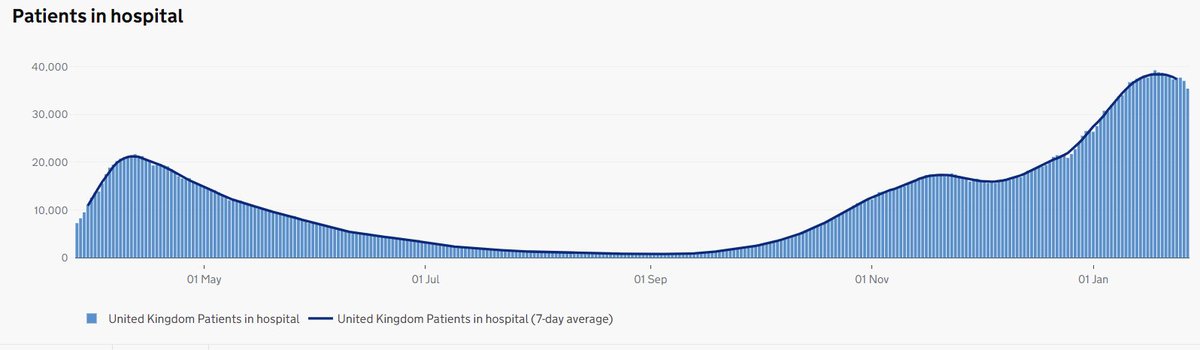

Sometimes doctors argue about new treatments. One group may want every patient to be given the treatment without delay while others first want to see evidence from clinical trials. The pandemic provides many examples of why clinical trials are needed. 11/15

Hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, lopinavir–ritonavir and convalescent plasma are all examples of treatments that many doctors wanted to use in every patient. Clinical effectiveness trials showed that none of them helped. A treatment which does not work, can only do harm. 12/15

We also see some treatments which have only modest benefit. So we use them but only in carefully selected patients. The anti-viral drug Remdesivir is a good example. Some think the anti-inflammatory drug Tocilizumab should be in this category too. 13/15

Then there are treatments which do work. We wouldn’t be using dexamethasone in every patient if it wasn’t for strong evidence from a large clinical trial. Some doctors (like me) were worried about side-effects. Whatever the answer, clinical trials improve patient care. 14/15

The pandemic has put the value of large clinical effectiveness trials beyond doubt. The culture of medicine must change to make them quicker and easier to deliver. Through @NIHRresearch, the UK leads the world in this type of research, but we could still be so much better. 15/15

PS In the case of Vitamin D, the evidence isn't there yet to implement a policy where we prescribe it to everyone. We only have data from small trials and some of these have problems which make them hard to interpret. But large effectiveness trials are under way.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh