THREAD: More on the Birth Narratives.

Each year, Nativity plays combine aspects of Matthew and Luke’s narratives into a single drama (or something like one).

The journey to Bethlehem, the shepherds, the wise men, a few camels for good measure (?):

so the list goes on.

Each year, Nativity plays combine aspects of Matthew and Luke’s narratives into a single drama (or something like one).

The journey to Bethlehem, the shepherds, the wise men, a few camels for good measure (?):

so the list goes on.

No small number of scholars, however, see Matthew and Luke’s narratives as fundamentally at odds with each another.

‘Not only do they tell completely different stories about how Jesus was born’, @BartEhrman says, ‘some of their differences appear to be irreconcilable’.

‘Not only do they tell completely different stories about how Jesus was born’, @BartEhrman says, ‘some of their differences appear to be irreconcilable’.

So then, let’s see how different Matthew and Luke’s narratives really are.

Below are their main components, set out side by side (in what I take to be their implied chronological order).

Below are their main components, set out side by side (in what I take to be their implied chronological order).

Despite what’s often claimed, Matthew and Luke’s narratives seem to dovetail quite neatly.

The first point we should note is their *commonalities*.

The first point we should note is their *commonalities*.

🔹 Both narratives open with a description of a couple (Mary and Joseph) who are engaged to be married, but don’t yet enjoy a sexual relationship.

🔹 Both describe Joseph as a man of Davidic descent.

🔹 Both have Mary conceive by the agency of the Holy Spirit.

🔹 Both describe Joseph as a man of Davidic descent.

🔹 Both have Mary conceive by the agency of the Holy Spirit.

🔹 Both have Jesus named in advance by an angelic visitor.

🔹 Both have Jesus born in Bethlehem, at which point Mary and Joseph live together.

🔹 And both have Jesus grow up in Nazareth.

Matthew and Luke’s narratives thus share a common core.

🔹 Both have Jesus born in Bethlehem, at which point Mary and Joseph live together.

🔹 And both have Jesus grow up in Nazareth.

Matthew and Luke’s narratives thus share a common core.

But what about their differences?

Well, for a start, their differences don’t seem accidental.

Rather, each narrative focuses on the actions of a different *person*.

Well, for a start, their differences don’t seem accidental.

Rather, each narrative focuses on the actions of a different *person*.

Aside from a brief excursus (which describes the visit of the wise men from the wise men’s perspective: Matt. 2.1–12), the main actor in Matthew’s narrative is Joseph:

🔹 it’s Joseph who’s visited by an angel in a dream;

🔹 it’s Joseph who’s visited by an angel in a dream;

🔹 Joseph’s decision to marry Mary then drives the narrative forward (1.24 w. 19);

🔹 it’s Joseph who assigns Jesus his name—an event which Luke recounts in the passive voice (cp. Matt. 1.25 w. Luke 2.21);

🔹 it’s Joseph who assigns Jesus his name—an event which Luke recounts in the passive voice (cp. Matt. 1.25 w. Luke 2.21);

🔹 Joseph ‘takes’ Jesus and Mary to Egypt and back again (courtesy of further dreams); and

🔹 it’s Joseph who’s ultimately said to settle in Nazareth (2.23). (His family would of course have accompanied with him, but only Joseph is mentioned.)

🔹 it’s Joseph who’s ultimately said to settle in Nazareth (2.23). (His family would of course have accompanied with him, but only Joseph is mentioned.)

Meanwhile, aside from a brief excursus (which narrates the experience of the shepherds from the shepherds’ perspective: Luke 2.8–15), the main actor in Luke’s narrative is *Mary*:

🔹 it’s Mary who’s visited by an angel;

🔹 Mary then arises to go to Judah (to see Elizabeth);

🔹 it’s Mary who’s visited by an angel;

🔹 Mary then arises to go to Judah (to see Elizabeth);

🔹 although it’s Joseph who travels up to Bethlehem, he only does so in response to Augustus’s decree;

🔹 it’s Mary whom the shepherds first encounter (2.16) and who’s struck by their story;

🔹 it’s Mary who’s purified (along with Jesus) (2.22); and

🔹 it’s Mary whom the shepherds first encounter (2.16) and who’s struck by their story;

🔹 it’s Mary who’s purified (along with Jesus) (2.22); and

🔹 it’s Mary to whom Simeon’s prophecy is addressed.

Hence, while Matthew focuses on Joseph’s actions (and/or Joseph-based sources), Luke focuses on Mary’s,

which may explain other features of our authors’ narratives.

Hence, while Matthew focuses on Joseph’s actions (and/or Joseph-based sources), Luke focuses on Mary’s,

which may explain other features of our authors’ narratives.

For instance, Joseph may have been more concerned than Mary about Herod’s actions (and more interested in the wise men’s story), since it was his responsibility to keep the family safe...

...and since he was the one warned in a dream not to stay in Bethlehem (or return to Judah),

which may explain why Matthew (rather than Luke) records Herod’s encounter with the wise men and the massacre of Bethlehem’s children.

which may explain why Matthew (rather than Luke) records Herod’s encounter with the wise men and the massacre of Bethlehem’s children.

Meanwhile, Mary may have been more concerned than Joseph about the family’s relocation to Bethlehem (especially if she didn’t know Joseph’s relatives there),

and Mary was clearly more struck by the shepherds’ words (2.19) and more involved in events at the Temple (2.22, 34),

and Mary was clearly more struck by the shepherds’ words (2.19) and more involved in events at the Temple (2.22, 34),

which may explain why Luke (rather than Matthew) records such events.

—————— CHRONOLOGY ——————

With these things in mind, let’s turn our attention to chronological matters.

Matthew and Luke’s narratives have an implicit order.

With these things in mind, let’s turn our attention to chronological matters.

Matthew and Luke’s narratives have an implicit order.

The family can’t flee to Egypt until Jesus has been presented at the Temple, and Jesus can’t be presented at the Temple until the shepherds have arrived (Luke 2.20–22).

Given these constraints, how well do Matthew and Luke’s narratives fit together?

Given these constraints, how well do Matthew and Luke’s narratives fit together?

To my mind, they fit together very neatly.

The events described by Luke are set immediately after Jesus’ birth: Jesus is circumcised on his 8th day and is presented at the Temple on his 40th day (Lev. 12).

The events described by Matthew, however, are set much later.

The events described by Luke are set immediately after Jesus’ birth: Jesus is circumcised on his 8th day and is presented at the Temple on his 40th day (Lev. 12).

The events described by Matthew, however, are set much later.

Herod tells his soldiers to slaughter every male aged two or under, in which case Jesus must have been at least a year old at the time.

And, unlike Luke, Matthew never refers to Jesus as a ‘baby’ or mentions an ‘inn’.

And, unlike Luke, Matthew never refers to Jesus as a ‘baby’ or mentions an ‘inn’.

Whereas Luke has the shepherds visit a ‘baby’ in an ‘inn’, Matthew has the wise men visit a ‘child’ in a ‘house’ (cp. Matt. 2.11 w. Luke 2.7, 16), presumably because Joseph has found a more permanent residence in Bethlehem by then.

———— PERCEIVED INCONSISTENCIES ————

Matthew and Luke’s narratives seem (to me at least) to fit together very neatly.

So why do so many scholars charge Matthew and Luke with incoherence?

Part of the answer is because they read them in a very stilted fashion.

Matthew and Luke’s narratives seem (to me at least) to fit together very neatly.

So why do so many scholars charge Matthew and Luke with incoherence?

Part of the answer is because they read them in a very stilted fashion.

‘In Matthew’s account of Jesus’ birth’, Ehrman says, ‘Joseph and Mary aren’t originally from Nazareth but from *Bethlehem*. ...They live there...and they’re still there a year or more after Jesus’ birth. ...

...So how can Luke be right when he says Mary and Joseph are from Nazareth and return there a month or so after Jesus’ birth?’.

At first blush, Ehrman’s question/claim seems a forceful one.

On closer inspection, however, it turns out to depend on two significant inferences,

At first blush, Ehrman’s question/claim seems a forceful one.

On closer inspection, however, it turns out to depend on two significant inferences,

...both of which are at best debatable.

Contra the impression given by Ehrman, Matthew doesn’t tell us Joseph *didn’t* live in Nazareth,

nor does Luke tell us Joseph went *directly* back to Nazareth after Jesus’ presentation at the Temple. These are inferences.

Contra the impression given by Ehrman, Matthew doesn’t tell us Joseph *didn’t* live in Nazareth,

nor does Luke tell us Joseph went *directly* back to Nazareth after Jesus’ presentation at the Temple. These are inferences.

In the absence of evidence to the contrary, they’d be reasonable inferences.

That is to say, if Matthew 1–2 was our *only* account of Jesus’ birth, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume Joseph lived in Bethlehem,

That is to say, if Matthew 1–2 was our *only* account of Jesus’ birth, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume Joseph lived in Bethlehem,

and, if Luke 1–2 was our only account, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume Joseph went directly from the Temple to Nazareth.

But Matthew 1–2 *isn’t* our only account of Jesus’ birth, and nor is Luke 1–2.

But Matthew 1–2 *isn’t* our only account of Jesus’ birth, and nor is Luke 1–2.

And, since two accounts are available for us to study, shouldn’t we allow the extra insight they afford us to inform our interpretation of Matthew and Luke’s individual accounts rather than dismiss the extra insight they afford us as *precluded* by our individual accounts?

Isn’t that precisely why it’s preferable to work with two accounts rather than just one?

Of course, when two accounts are irreconcilable, we have to choose between them (or reject them both). But, as we’ve seen, Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives fit together very neatly.

Of course, when two accounts are irreconcilable, we have to choose between them (or reject them both). But, as we’ve seen, Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives fit together very neatly.

They only become irreconcilable if we adopt a methodology which precludes their reconciliation, e.g., if we take Matthew’s decision not to describe an incident as evidence *against* the historicity of Luke’s description of it.

But why should we analyse Matthew and Luke’s narratives in such a manner?

If we simply let each narrative inform our interpretation of the other, then the combined story they tell makes sense,

If we simply let each narrative inform our interpretation of the other, then the combined story they tell makes sense,

and, as we’ll now see, the way it comes together gives us reason to repose confidence in Matthew and Luke.

—————— COHERENCE ——————

As Ehrman rightly notes, considered in isolation, the text of Matthew 2.1–12 could plausibly be taken to imply Joseph lived in Bethlehem.

Yet Matthew himself casts doubt on such a notion,

As Ehrman rightly notes, considered in isolation, the text of Matthew 2.1–12 could plausibly be taken to imply Joseph lived in Bethlehem.

Yet Matthew himself casts doubt on such a notion,

...since, at the end of ch. 2, he tells us Joseph ‘withdrew to the district of Galilee and went and lived in a city called Nazareth’.

Why Nazareth of all places, especially given its lowly reputation (John 1.46)?

Why Nazareth of all places, especially given its lowly reputation (John 1.46)?

And why does Matthew later refer to an unidentified village in Galilee as Jesus’ ‘hometown/fatherland’ (πατρίς), as if to suggest his family have dwelt there for some time (13.52–58)?

The answer is provided for us by Luke: because Nazareth was Joseph’s hometown (Luke 2.4).

The answer is provided for us by Luke: because Nazareth was Joseph’s hometown (Luke 2.4).

Luke thus ties up a loose end in Matthew’s narrative.

And, at the same time, Matthew ties up a loose end in Luke.

Luke portrays Joseph as a man with two places of origin.

In Luke 2.3, everyone is said to return ‘to their own town’ to be registered,

And, at the same time, Matthew ties up a loose end in Luke.

Luke portrays Joseph as a man with two places of origin.

In Luke 2.3, everyone is said to return ‘to their own town’ to be registered,

which, as we know, requires Joseph to go to Bethlehem (2.3).

And then, a few verses later, Joseph is said to return to ‘his own town’ of *Nazareth* (2.39).

How many of his ‘own towns’ can a man have? Joseph seems to have two—which may also be reflected in the text of Luke 2.4,

And then, a few verses later, Joseph is said to return to ‘his own town’ of *Nazareth* (2.39).

How many of his ‘own towns’ can a man have? Joseph seems to have two—which may also be reflected in the text of Luke 2.4,

where Luke describes Joseph as a man from ‘the house and line’ of David.

Why house *and* line?

The answer requires us to factor in the testimony of Matthew’s Gospel.

Why house *and* line?

The answer requires us to factor in the testimony of Matthew’s Gospel.

Joseph’s *line*, I submit, refers to his kinsmen in *Nazareth*’s ancestry, which Luke traces back to David’s son, Nathan (cp. Luke 3),

while Joseph’s *house* refers to his relationship to the ‘house of David’—i.e., the Davidic kings (cp. 1 Kgs. 12.19–26, 13.2, etc.)—,

while Joseph’s *house* refers to his relationship to the ‘house of David’—i.e., the Davidic kings (cp. 1 Kgs. 12.19–26, 13.2, etc.)—,

Or so I claim.

Additional evidence for my claim, however, can be proffered.

Consider, for a start, what the NT tells us about Jesus’ *background*.

Additional evidence for my claim, however, can be proffered.

Consider, for a start, what the NT tells us about Jesus’ *background*.

In the NT, Jesus’ background is enshrouded in a certain amount of confusion.

In all three Synoptic Gospels, Jesus is referred to as a ‘son of David’ (e.g., Matt. 20.30–31 // Mark 10.47–48 // Luke 18.38–39, Luke 2.4)—a title which Paul takes literally (Rom. 1.3)...

In all three Synoptic Gospels, Jesus is referred to as a ‘son of David’ (e.g., Matt. 20.30–31 // Mark 10.47–48 // Luke 18.38–39, Luke 2.4)—a title which Paul takes literally (Rom. 1.3)...

...and to which Jesus’ relatives laid claim (cp. Africanus’ Epistle to Aristides)—,

yet, in these same Gospels, Jesus is spoken about as if his ancestry is unremarkable (cp. Matt. 13.55, Mark 6.3, Luke 4.22 w. John 1.46, 7.41–42). (‘Isn’t he the carpenter’s son?’)

yet, in these same Gospels, Jesus is spoken about as if his ancestry is unremarkable (cp. Matt. 13.55, Mark 6.3, Luke 4.22 w. John 1.46, 7.41–42). (‘Isn’t he the carpenter’s son?’)

Viewed as a combined narrative, Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives are able to explain both items of evidence:

Joseph was a descendant of Jechoniah (per Matthew’s genealogy) with a history in Bethlehem, but at some point his ancestors relocated to Nazareth,

Joseph was a descendant of Jechoniah (per Matthew’s genealogy) with a history in Bethlehem, but at some point his ancestors relocated to Nazareth,

which meant his status as a descendant of Jechoniah wasn’t well known.

Also relevant to consider are the names of Jesus’ brothers: ‘Jacob’, ‘Joseph’, ‘Simon’, and ‘Judah’ (Matt. 13.55, Mark 6.3).

In Jesus’ day, families liked to recycle the names of their ancestors (cp. the discussion of John the Baptist’s name in Luke 1.59–61).

In Jesus’ day, families liked to recycle the names of their ancestors (cp. the discussion of John the Baptist’s name in Luke 1.59–61).

And, where Luke’s genealogy diverges from Matthew’s, it includes three of the names of Jesus’ four brothers (‘Joseph’, ‘Simon’, and ‘Judah’) while Matthew’s post-Davidic genealogy doesn’t include any of them.

The names of Jesus’ brothers thus seem to be more at home within Luke’s genealogy than within Matthew’s,

which is consistent with—and may help us expand—our claim about Joseph’s relocation.

which is consistent with—and may help us expand—our claim about Joseph’s relocation.

Apparently, Joseph’s ancestors didn’t simply leave Bethlehem and relocate to Nazareth;

there, they also became part of a different branch of David’s family tree, possibly as a result of a Levirate marriage (or similar),

there, they also became part of a different branch of David’s family tree, possibly as a result of a Levirate marriage (or similar),

at which point they began to choose names from their *new* family line (Luke’s genealogy) rather than their old one (Matthew’s).

Consequently, their family’s names look more at home within Luke’s genealogy than within Matthew’s. (Perhaps, for instance, Eleazar relocated, married, and died soon afterwards, and Levi then raised up children on his behalf.)

That may, of course, strike those who aren’t familiar with the messiness of ancient genealogies as an extravagant hypothesis,

but in ancient Israel—a land where Levirate marriages were enshrined in Mosaic law—it wasn’t uncommon for people to have multiple ancestries.

but in ancient Israel—a land where Levirate marriages were enshrined in Mosaic law—it wasn’t uncommon for people to have multiple ancestries.

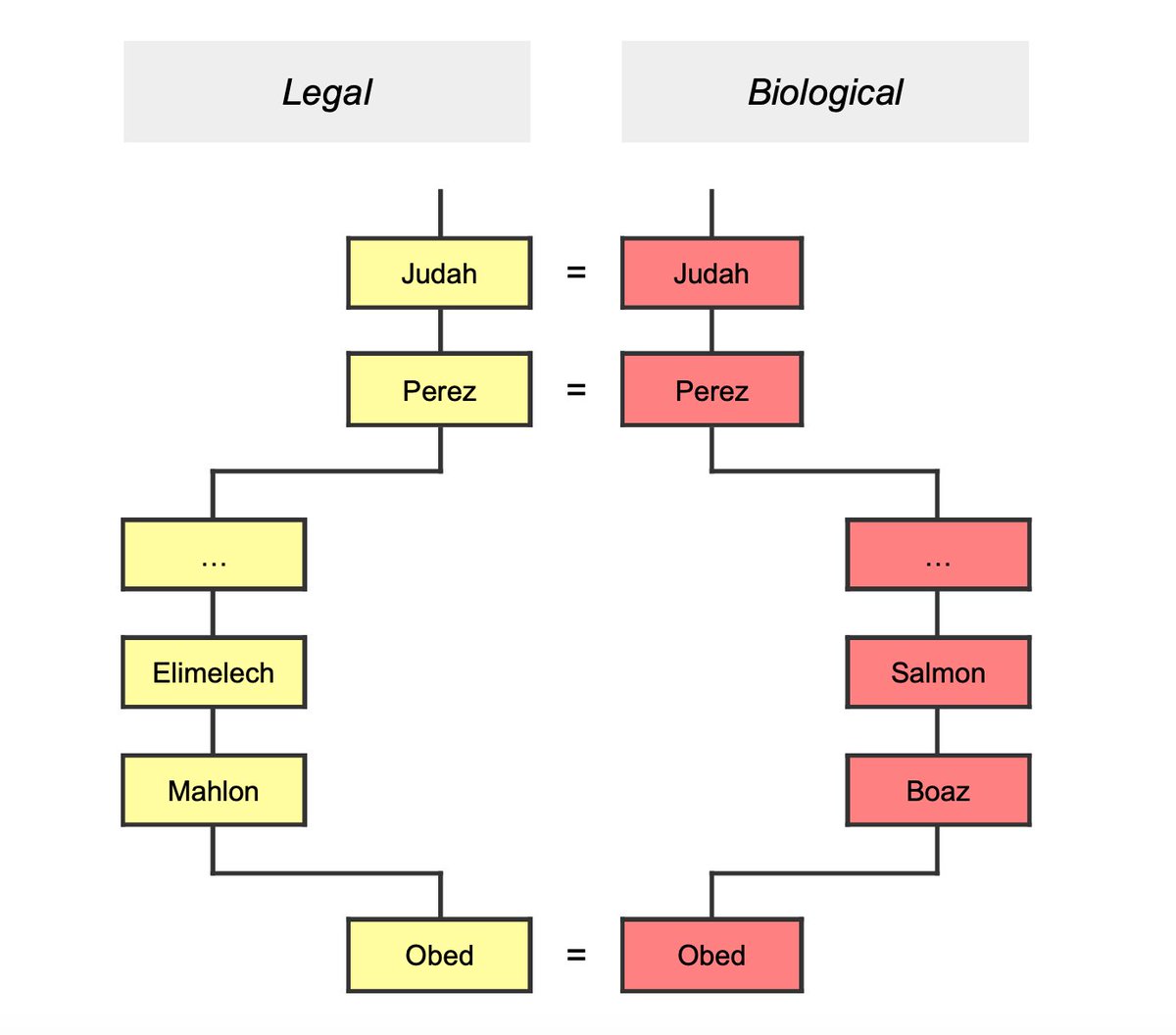

Indeed, both Matthew and Luke’s genealogies include at least one other case in point: the ancestry of Obed.

Obed was fathered by Boaz in order to continue the name/line of Ruth’s husband, Mahlon (Ruth 4.10).

Obed was fathered by Boaz in order to continue the name/line of Ruth’s husband, Mahlon (Ruth 4.10).

As a result, Obed’s ancestry could be traced either through his legal line (Mahlon, Elimelech, etc.) or through his biological line (Boaz, Salmon, etc.).

The same is true of Zerubbabel’s ancestry (though we won’t go into the details here: cp 1 Chr. 3.17–19).

And it’s also true, I submit, in the case of Matthan/Matthat.

Of course, other explanations of the differences between Matthew and Luke’s genealogies are possible.

And it’s also true, I submit, in the case of Matthan/Matthat.

Of course, other explanations of the differences between Matthew and Luke’s genealogies are possible.

We can always, for instance, dismiss them as errant or ‘made up’. (‘Each author gave his account of Jesus’ ancestry as well as he could’, Ehrman says, ‘but their accounts ended up different’.)

But such treatments of Matthew and Luke seem too simplistic.

But such treatments of Matthew and Luke seem too simplistic.

At least in terms of the pre-exilic section of his genealogy, Luke’s divergence from Matthew’s isn’t simply a mistake.

Luke was no stranger to the OT. He could easily have traced the ancestry of Shealtiel back to David by means of 1 Chr. 3, but he chose not to.

Luke was no stranger to the OT. He could easily have traced the ancestry of Shealtiel back to David by means of 1 Chr. 3, but he chose not to.

He evidently had additional information available to him, which he made use of. And the end result of his efforts is a credible genealogy.

It takes us from David (born 1040 BC) to Joseph (born 30 BC) in 41 generations, which makes an average of 25 years per generation.

It takes us from David (born 1040 BC) to Joseph (born 30 BC) in 41 generations, which makes an average of 25 years per generation.

It connects Joseph back to a known descendant of David, viz. Nathan (1 Chr. 3.5), whose descendants are known to have preserved their identity as ‘Nathanites’.

(Since the Shimeites are a known clan of Levites [Num. 3.18], it makes sense to view the house of Nathan as a known clan of Davidites: Zech. 12.12–13.)

Where it diverges from Matthew’s, Luke’s genealogy includes a number of names built around the same root as the name ‘Nathan’ is (‘Matthat’ x 2, ‘Matthathias’ x 2, ‘Mattatha’), which isn’t true of Matthew’s genealogy.

And its names have a ring of authenticity.

And its names have a ring of authenticity.

🔹 The recurrence of the name ‘Joseph’ six generations apart is typical of genealogies of the time, such as Matthew’s (where the same/similar names are shaded the same colour)...

🔹 The names ‘Mattathias’ and ‘Jannai’—unattested in the OT—are known to have become popular in the intertestamental period, so it makes sense for them to appear in the post-exilic section of Luke’s genealogy but *not* in its pre-exilic section.

🔹 And, while Luke’s genealogy follows predictable patterns (cp. above), it’s not *too* predictable.

For instance, it contains the name ‘Hesli’, which isn’t attested elsewhere in Jewish literature (to my knowledge), yet is a credible ancient Near Eastern name.

For instance, it contains the name ‘Hesli’, which isn’t attested elsewhere in Jewish literature (to my knowledge), yet is a credible ancient Near Eastern name.

It derives from the Aramaic root ‘ḥ-s-l’ (‘to wean’), and resonates with all sorts of other Near Eastern names which are also derived from the verb ‘wean’, such as ‘Pirsatu’ (Babylonian), ‘Parisu’ (Ugaritic), ‘Patmon’ (Nabatean), and ‘Fatima’ (Arabic).

In sum, then, Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives aren’t merely *possible* to harmonise;

they can be shown to fit together with an (apparently) unintended neatness, which gives them considerable credibility.

they can be shown to fit together with an (apparently) unintended neatness, which gives them considerable credibility.

Rather than contradict one another, they tie up one another’s loose ends.

—————— CONCLUSION ——————

Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives are frequently dismissed as irreconcilable, which is understandable.

They’re not written in the same way as modern narratives, and they describe a complex and (to most people) unfamiliar state of affairs.

Matthew and Luke’s birth narratives are frequently dismissed as irreconcilable, which is understandable.

They’re not written in the same way as modern narratives, and they describe a complex and (to most people) unfamiliar state of affairs.

When studied sympathetically, however, Matthew and Luke’s narratives can be seen to tell a coherent story, as is so often the case when Scripture is studied sympathetically.

Of course, my interpretation of Matthew and Luke is just that—an interpretation—, and it leaves a number of questions unanswered.

For instance, is it really plausible to think Luke knew about an event as dramatic as Herod’s massacre of Bethlehem’s children and chose not to mention it?

But one thing at a time.

But one thing at a time.

I’ll try to say a bit more about Matthew and Luke’s selection of material (and its theological purpose) in a couple of weeks.

Please Re-Tweet if this has been useful.

</END>

Please Re-Tweet if this has been useful.

</END>

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh