RIP His Royal Highness Prince Philip.

Prince Philip's war service is usually summarised as getting a Mention in Despatches at the Battle of Cape Matapan and saving HMS Wallace at Sicily. But I feel this overlooks so much more, and occasionally errors creep in, so here we go.

Prince Philip's war service is usually summarised as getting a Mention in Despatches at the Battle of Cape Matapan and saving HMS Wallace at Sicily. But I feel this overlooks so much more, and occasionally errors creep in, so here we go.

After completing officer training at Dartmouth, on 23 February 1940 the 18 year old midshipman joined HMS Ramillies at Colombo. He would spend most of 1940 with the venerable battleship and the cruisers Kent and Shropshire. 📷 IWM A8858

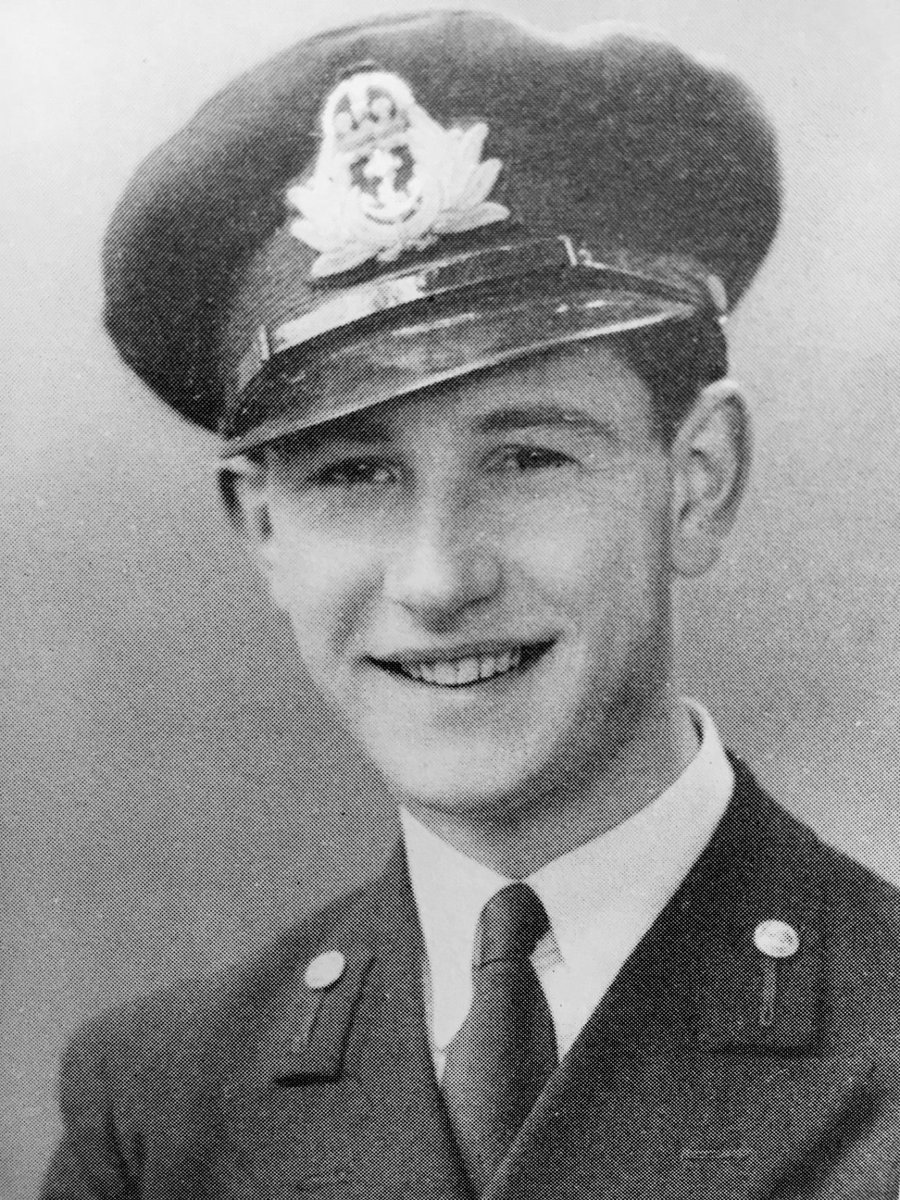

Early in 1941 he joined the battleship HMS Valiant in the Mediterranean. The Royal website confusingly claims that Philip joined HMS Valiant at the age of 17, which isn’t really possible. It appears he joined her in January 1941, at the age of 19. 📷IWM A12126

Probably thanks to a dodgy Wikipedia entry, he’s often said to have gone back to the UK in early 1941, taken a load of training courses, and then returned to Valiant as a lieutenant. This sort of thing didn’t happen – the courses were later (see further below).

Almost immediately on joining, he saw his first action when Valiant, part of a larger fleet, bombarded the town of Bardia in support of Operation Compass 📷State Library of Victoria H98.105/3251. It is Valiant, it's probably not Bardia!

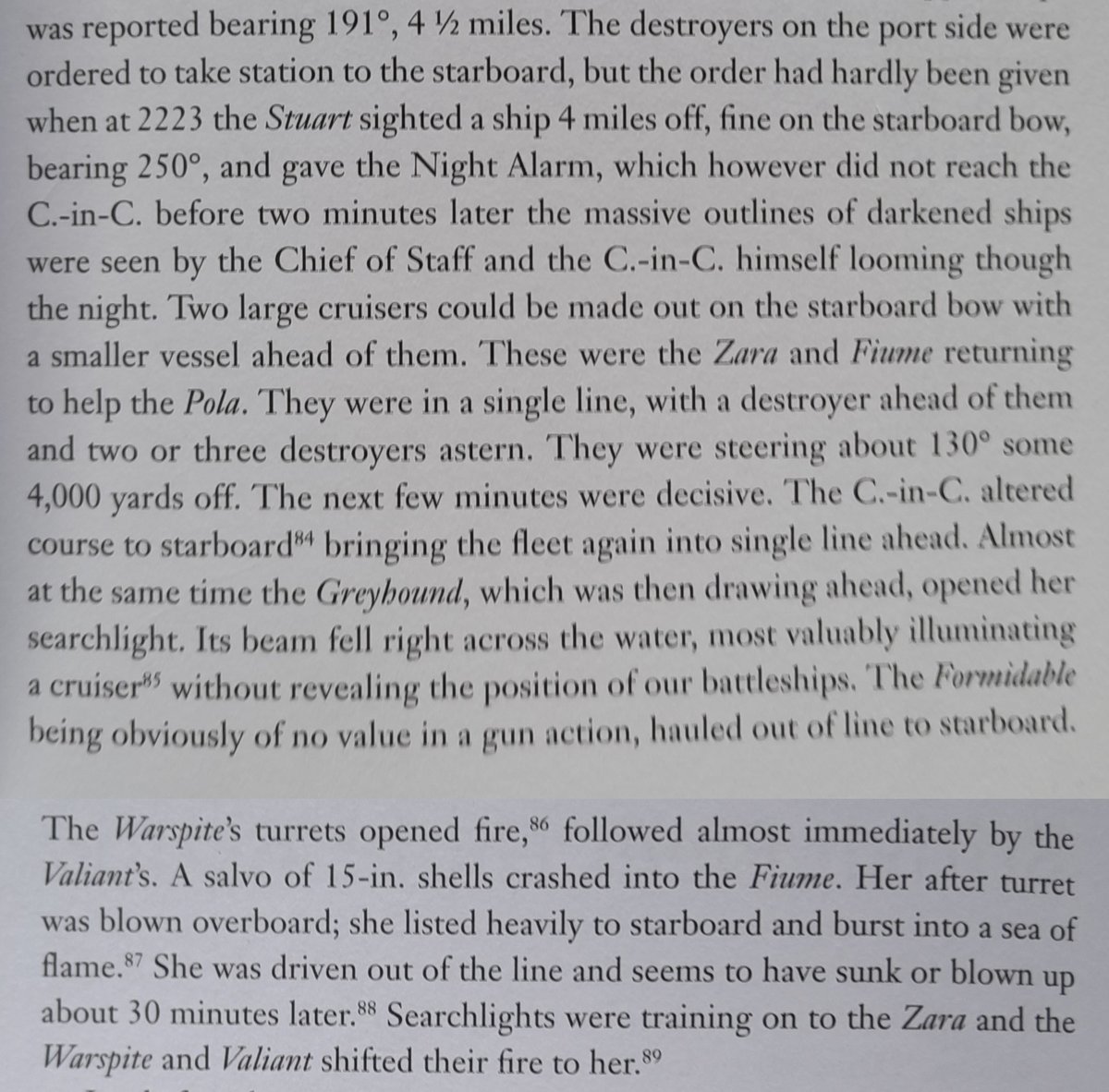

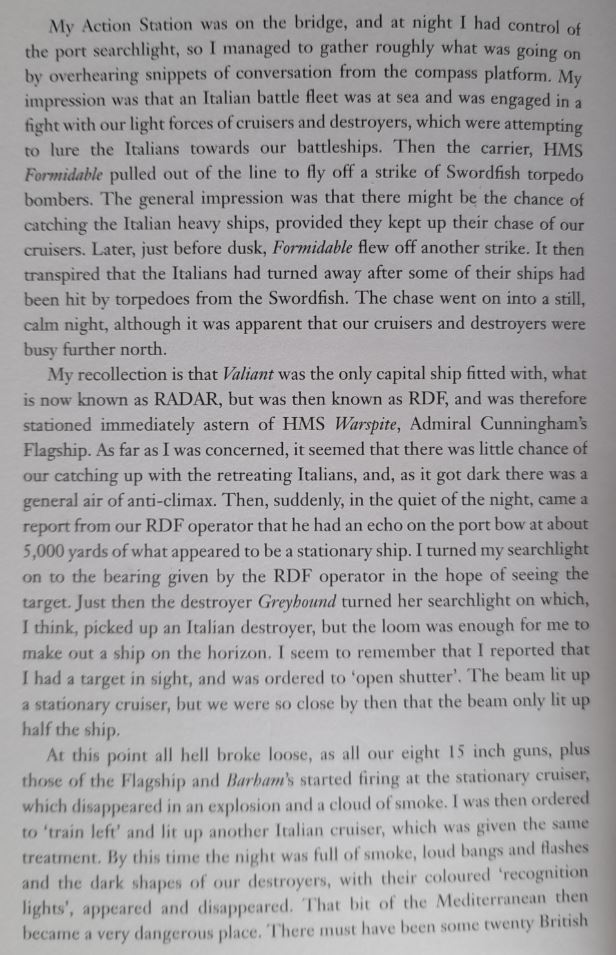

He was on Valiant at the Battle of Matapan, when the RN and RAN engaged an Italian fleet south of Greece on 28 March 1941. The battle was an overwhelming Allied victory, with only light damage and 3 killed, for the sinking of 3 Italian cruisers and 2 destroyers. 📷AWM P00090.108

Philip’s role has been misdescribed recently, and sometimes exaggerated to commanding a 'battery' of searchlights and even being the person who ‘found’ the enemy fleet in the night action. Here is the Naval staff history, and Philip’s own words on his role.

His next posting was back to Britain, where he attended numerous courses at Portsmouth. In September he became an acting sub lieutenant and early in 1942 became a full sub-lieutenant shortly after he joined HMS Wallace on the East Coast.📷IWM FL10546

Philip would spend the next year on the East Coast, a largely forgotten battlefront, escorting convoys up and down the coast. This was his single longest campaign and bears a bit more detail. You can learn a lot from @NickHewitt4's excellent book on it. amazon.co.uk/Coastal-Convoy…

The convoys were vital to Britain’s war effort, carrying nearly 13 million tons of coal and 2 million tons of cargo each year. But they were vulnerable to S-boats operating from the Dutch and Belgian coasts. 📷Getty

On the night of 14/15 March, Philip met the Kriegsmarine for the first time during an attack by S-boats on convoy FN655. Wallace tangled with boats of the 4th Flotilla and with fellow escorts, saw them off. 📷No idea, sorry!

But that same night, the danger of their work was clearly highlighted by the loss of HMS Vortigern, sunk by S-boat S-104. There were only 14 survivors. 📷IWM Q75528

Wallace tangled with S-boats again on 14 December when 3 flotillas attacked convoy FN889. 2 flotillas attacked the escorts, with 2 torpedoes passing close by Wallace's bow – from different directions. With the escorts engaged, the 3rd flotilla sank 5 merchant ships. 📷AWM 128144

But the vast majority of convoys that Wallace escorted made it, thanks to the escorts (including destroyers, trawlers and motor launches) and the Coastal Forces operating in the North Sea. THIS was arguably Prince Philip's greatest contribution to the war. 📷Getty

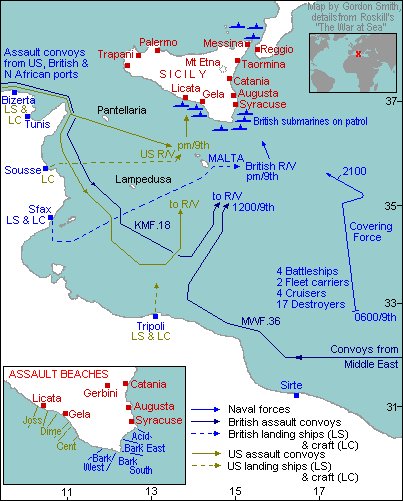

In early 1943, Wallace was ordered to transfer to the Med. The ship escorted a June merchant convoy into the Atlantic and then a portion of it to Gibraltar. They deployed into the Med to escort the invasion convoys bound for Sicily in Operation Husky. 📷Naval History Net

The invasion began on 9/10 July, with Wallace providing AA support for the landings in the Bark West sector at the south east tip of the island. Here she came under air attack on the night of 10/11 July and again on 13/14 July. 📷National Museum of U.S. Navy

I believe the action in which Prince Philip saved Wallace was the first, when bombers dropped flares to try and illuminate targets. Prince Philip and skipper Commander Duncan Carson had a small flaming raft made to distract the bombers. A stick of bombs narrowly missed Wallace.

There were other, slightly embarrassing incidents though. On 12/13 July, Wallace engaged an enemy target. Fortunately only one person was injured before the mistake was realised - they had accidentally engaged an Allied Landing Craft Infantry (Large). 📷Library & Archives Canada

In August 43 Wallace returned to the UK to resume East Coast convoy duties. By now Prince Philip was a full lieutenant (Dec 42) & had been 1st lt on Wallace since Oct 42 (at 21). He's often said to be one of the youngest 1st lieutenants in service, but I don't find this credible.

In early 1944 he was transferred to HMS Whelp, a new destroyer still completing at Hawthorn Leslie on the Tyne. Here he stood by the vessel during its final construction and took up post as first lieutenant when it commissioned in April. 📷IWM FL2728

I have wondered if he might have lodged with other crews standing by their vessels at the yard at the same time. If so, it was with Sub Lt Baggott, standing by #LCT7074. He must have seen the LCT which was at the yard at exactly the same time. I wonder what he made of her.

The 27th Destroyer Flotilla, of which Whelp was a part, was not part of the Royal Navy's order of battle for Neptune. Instead she went to Spitsbergen, helping to replenish the small garrison there. 📷Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

Her next destination was the Med to support Operation Dragoon. She left Portsmouth on 2 August, escorting HMS Ramillies, Prince Philip's first seagoing posting. In the event, she was selected to proceed to the Indian Ocean so wasn't involved with the landings in Southern France.

I think I'll take a break here and complete Prince Philip's service in the Far East tomorrow. Thank you for reading.

This has proven more popular than I anticipated so I'd better finish it off!

Like his earlier service, Prince Philip's time on Whelp is usually reduced to being present at the surrender in Tokyo Bay. This implies some sort of ceremonial function, which was far from the case.

Like his earlier service, Prince Philip's time on Whelp is usually reduced to being present at the surrender in Tokyo Bay. This implies some sort of ceremonial function, which was far from the case.

Like the East Coast convoys, in the Far East Prince Philip joined a campaign that has been largely forgotten, so it bears some explanation. A good intro for those in the mood can be found in this book (I didn't think it was so expensive!). amazon.co.uk/Task-Force-57-…

Simply put, the British Eastern Fleet, mauled by the Japanese in 1942, was slowly rebuilt in the Bay of Bengal, with Trincomalee as the fleet base. Another book that I'm sure details this well is this one (I don't have it sadly). amazon.co.uk/British-Pacifi…

In late 1944 the fleet was significantly bolstered with more warships, landing craft and a considerable 'fleet train'. The latter was necessary to sustain the fleet at sea: the vast distances in the Pacific and Indian Oceans prohibited operating from ports in the usual manner.

Chief amongst the warships were 18 aircraft carriers, who would operate alongside the US Navy task forces in the Pacific. With them came escort destroyers, including HMS Whelp, who arrived with the 27th Flotilla in October 1944. 📷IWM MH5309

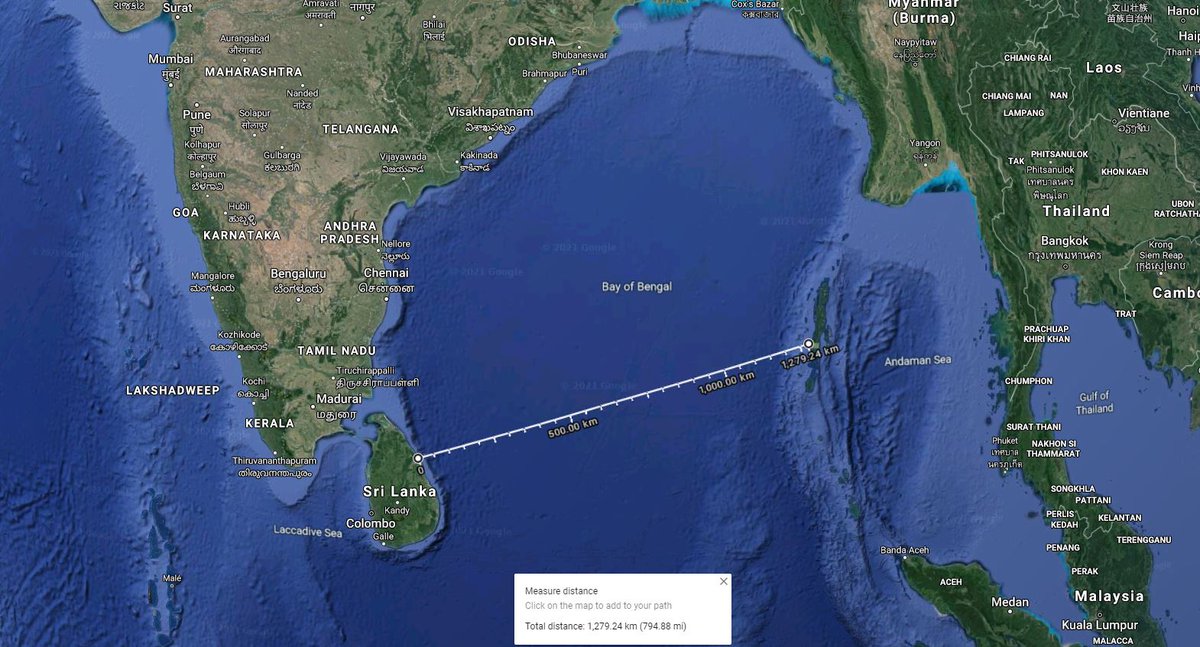

Prince Philip, 1st lieutenant to Commander Norfolk on Whelp, first encountered the Japanese on 17 October during Operation Millet, a bombardment and carrier strike on the Nicobar Islands (800 miles from Trincomalee), intended to divert Japanese attention from Leyte Gulf. 📷Google

The attacks provided useful experience for the fledgling fleet. Late in the operation, they came under attack from 12 torpedo bombers. Seven were shot down for the loss of 3 fighters, but it signalled that aircraft were the chief Japanese threat.

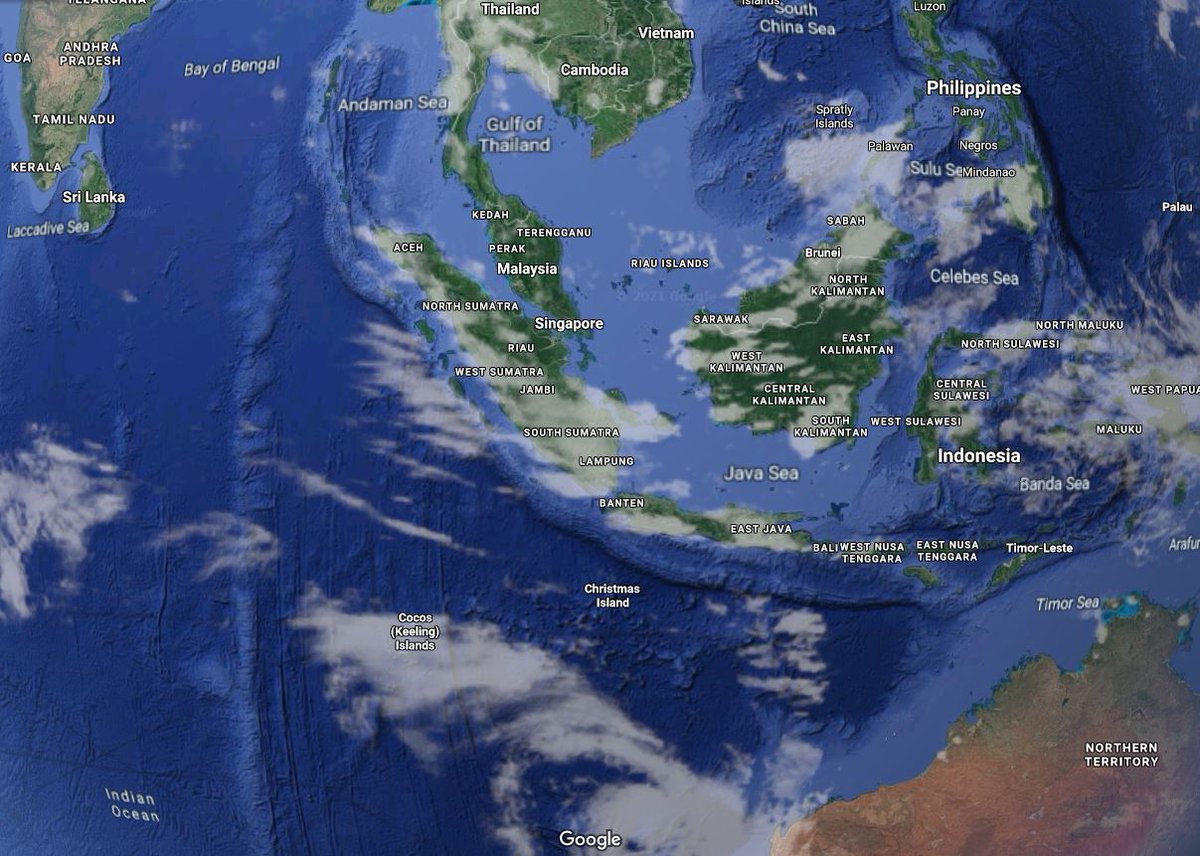

In November 44, the greater part of the Eastern Fleet was formed into the British Pacific Fleet. That month they began a series of missions under the overall operation 'Outflank'. These were primarily raids on oil facilities in Sumatra as the fleet prepared to move east. 📷Google

In Operation Robson in November, Whelp and Wager escorted the fleet's fuel tanker Wave King, whilst the main strike force sailed closer to the northern tip of Sumatra to attack Pangkalan Brandan. The raid was broadly successful, although there was next to no opposition.

In January, Operation Lentil saw Whelp with the main strike force. It was the Royal Navy's heaviest carrier strike to date with 88 aircraft attacking Pangkalan Brandan again, including Gruman Avenger bombers (seen forming up below), Corsairs, Hellcats and Fireflies. 📷IWM A27166

Whelp was detached from the strike force a little early though. To the north, HMS Shakespeare had engaged a Japanese warship on the surface near the Andaman Islands and sustained damage. Whelp took over from HMS Raider to tow her back to Trincomalee. 📷IWM FL6117

On 16 January, Whelp left Trincomalee as the BPF redeployed to Australia. On their way, they took the opportunity to raid more oil facilities on Sumatra in Operations Meridian 1 and 2. @ArmouredCarrier has done some good films on these, starting here.

They were the largest carrier raids of the Royal Navy's war, employing 105 aircraft in Meridian 1. Both raids were successful, with significant damage to the oil facilities. For much more detail, read @ArmouredCarrier's article here: armouredcarriers.com/operation-meri…

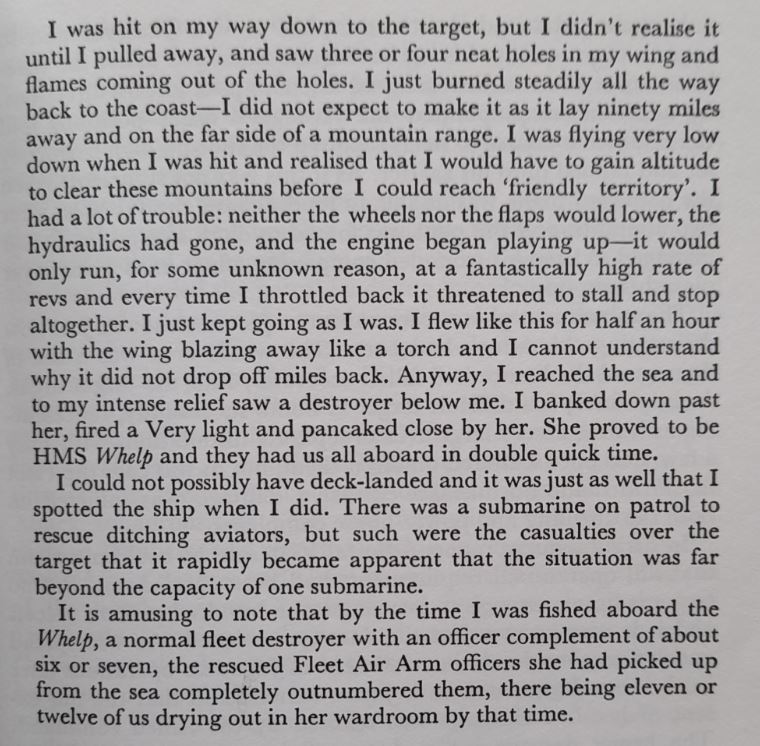

Whelp was part of the forward AA screen in Meridian 2, and as such was one of the first ships that the returning aircraft saw. For Sub Lieutenant Halliday and his 2 crew, Whelp was a genuine lifesaver when they sustained damage over the refineries.📷IWM A29242

Here's Halliday's own account of their return flight and rescue by Whelp (shamelessly borrowed from Task Force 57 by Peter Smith).

For a bit more on this, there's also a very good 1/2 hour radio programme covering the raid and rescue. It's well worth a listen. bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00…

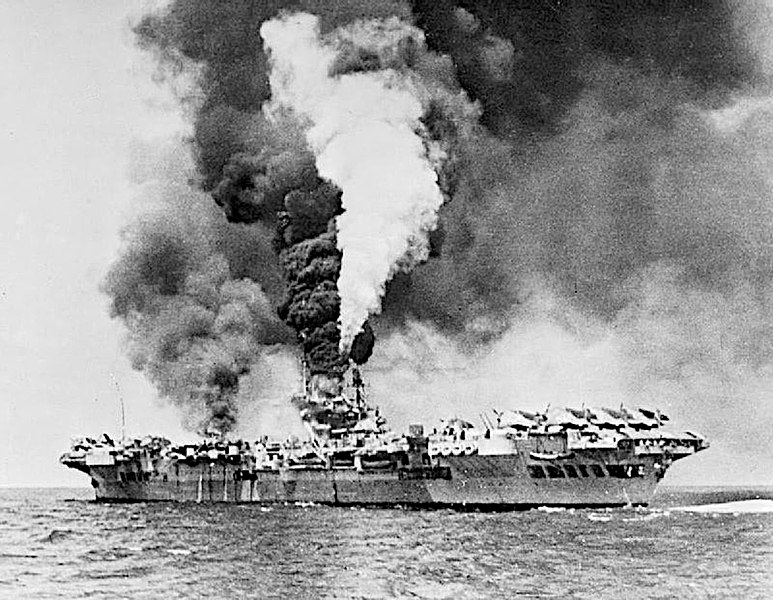

In March the BPF sailed north from Australia into the Pacific, bound for Okinawa. Whelp missed the opening invasion owing to radar defects but she returned to the fleet a few days later and Prince Philip witnessed the kamikaze attacks on the combined fleets. 📷IWM A29717

The fleet retired to the Philippines in May and Whelp escorted HMS Illustrious, badly damaged by a kamikaze, to Sydney for repairs. Once at Australia, Whelp also remained until July for repairs.📷AWM

On completion, Whelp escorted HMS Duke of York to Guam. In August the Allied fleets sailed for Tokyo, with Whelp allegedly the first Allied ship to enter Sagami Bay, outside Tokyo Harbour. 📷Naval History and Heritage Command. DoY is 2nd ship from front. Mt Fuji in background.

Prince Philip was present at the Japanese surrender on 2 September but he was not on board USS Missouri & was not a dignitary. He watched from the deck of Whelp, as did all her crew and those from the well over 200 Allied vessels in attendance. 📷Naval History & Heritage Command.

HMS Whelp then sailed south to Hong Kong to administer the Japanese surrender there. He remained with the ship as she slowly made her way back to the UK, arriving on 17 January 1946. He asked King George for Elizabeth's hand in marriage that summer.📷Navy Photos/George Knight

It should be fairly obvious by now, but Prince Philip was not shielded from danger and only sent on soft postings. The only time he was kept away from action was in 1940 when, as a Greek subject, he was technically not at war (Italy solved this for him in late 1940).

He had dangerous assignments, where people in his place on the next ship in line were killed doing exactly the same job. They were unglamorous and underappreciated – especially his work on the East Coast convoys.

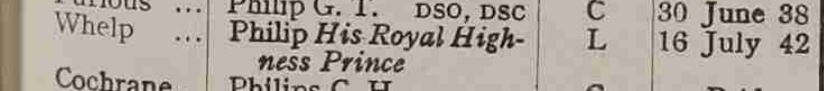

Nor was he given rapid promotion or undue honours on account of his status. He was a prince yes, but it only warranted him an unusual entry in the Navy Lists!

Similarly, I don't put much stock in the claim, repeated a lot yesterday & today, that he was the youngest 1st lieutenant in the Royal Navy. There were plenty of younger skippers. Even if you only count destroyer sized ships it wasn't unusual to have 21 year old 1st lieutenants.

Put simply, Prince Philip's wartime career was not unusual. He took the same path, sailed the same ships and seas, and faced the same dangers as many thousands of men his age. That's not to say he wasn't anything special. They were all special.

Rest in peace your Highness.

Rest in peace your Highness.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh