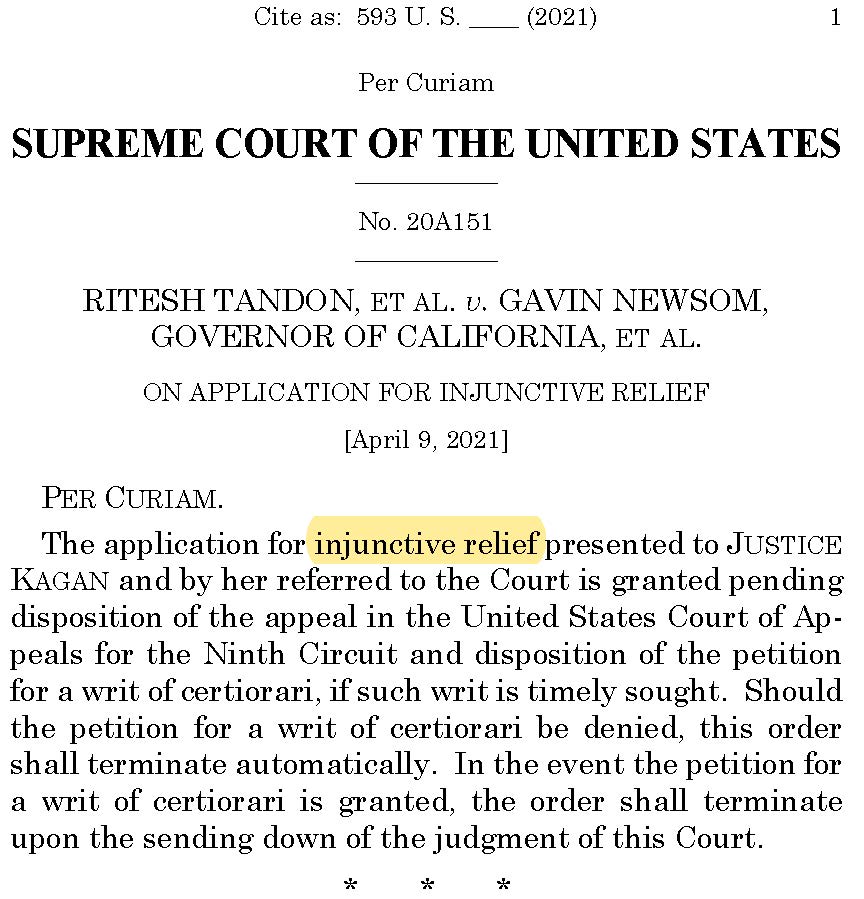

#SCOTUS issued another significant ruling on its "shadow docket" late last night, voting 5-4 to block California's #COVID-based restrictions on in-home gatherings insofar as they interfere with religious practice:

supremecourt.gov/opinions/20pdf…

How often is this happening?

A #thread:

supremecourt.gov/opinions/20pdf…

How often is this happening?

A #thread:

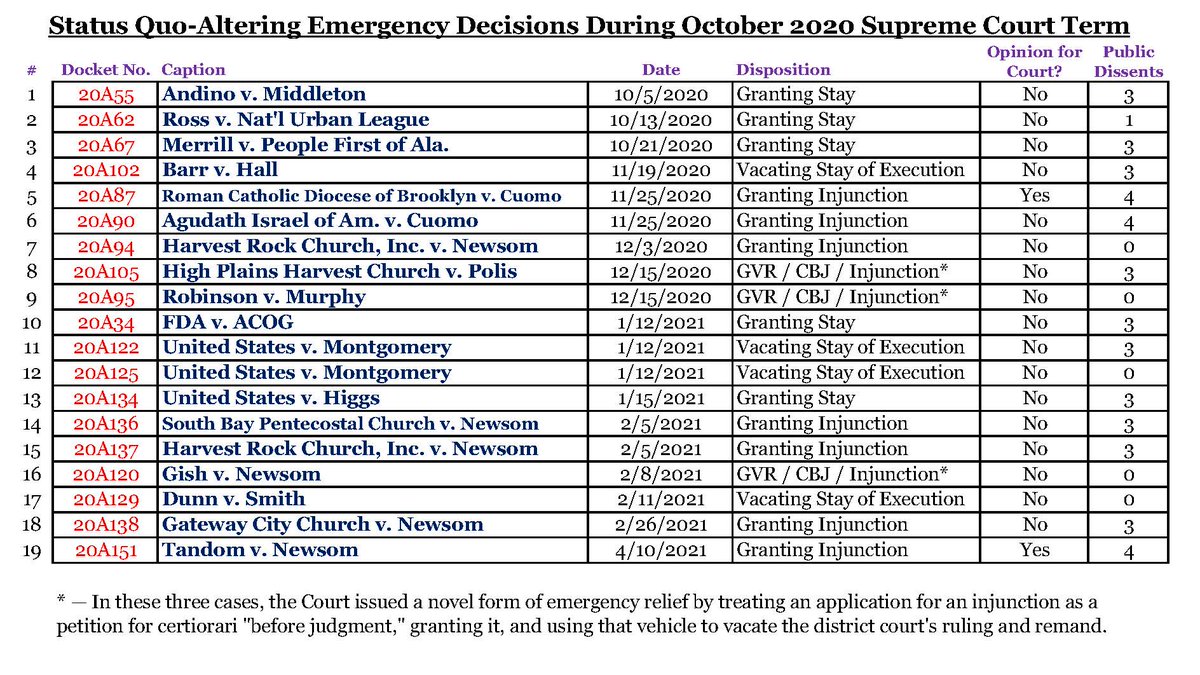

As the chart notes, this is (at least) the *19th* time this Term (since 10/5/2020) that the Justices have used such an emergency ruling to alter the status quo—whether by staying a lower-court ruling; lifting a lower-court stay; or, as here, directly enjoining a government actor.

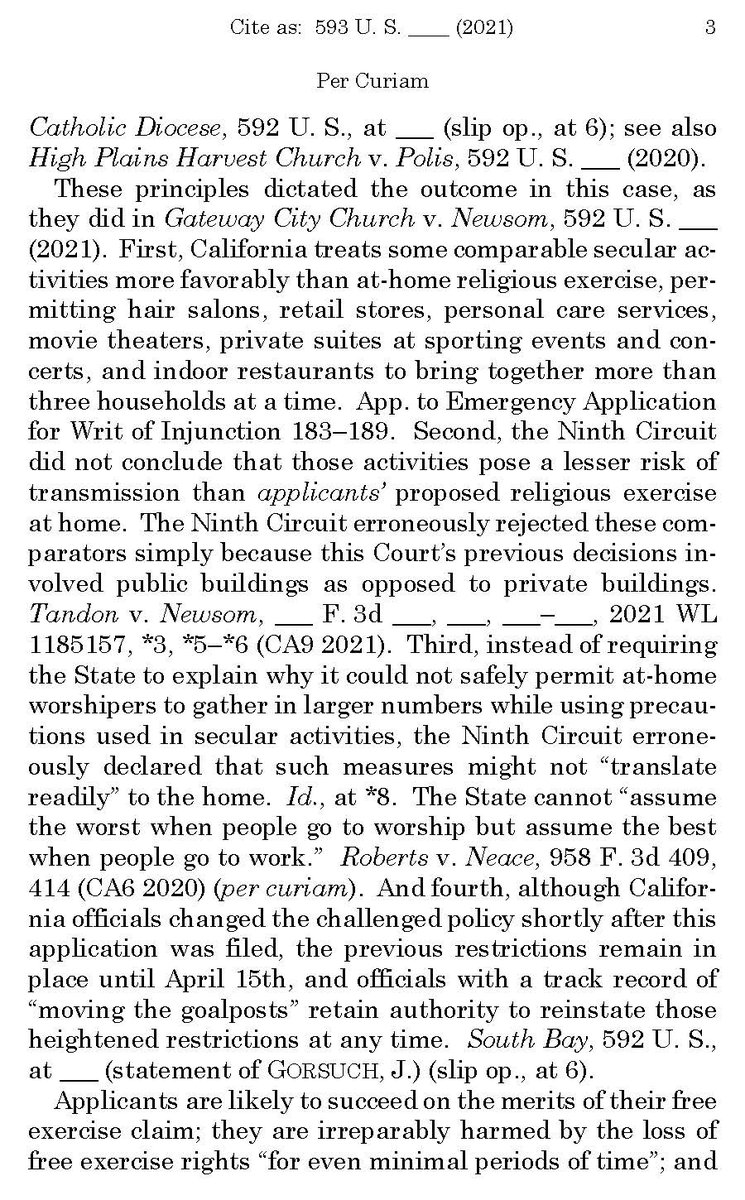

It's also only the *second* time in these 19 cases that the majority chose to write an opinion *for the Court* that provides a rationale for the decision (and the first such opinion in one of these California cases), even if it's a brief one:

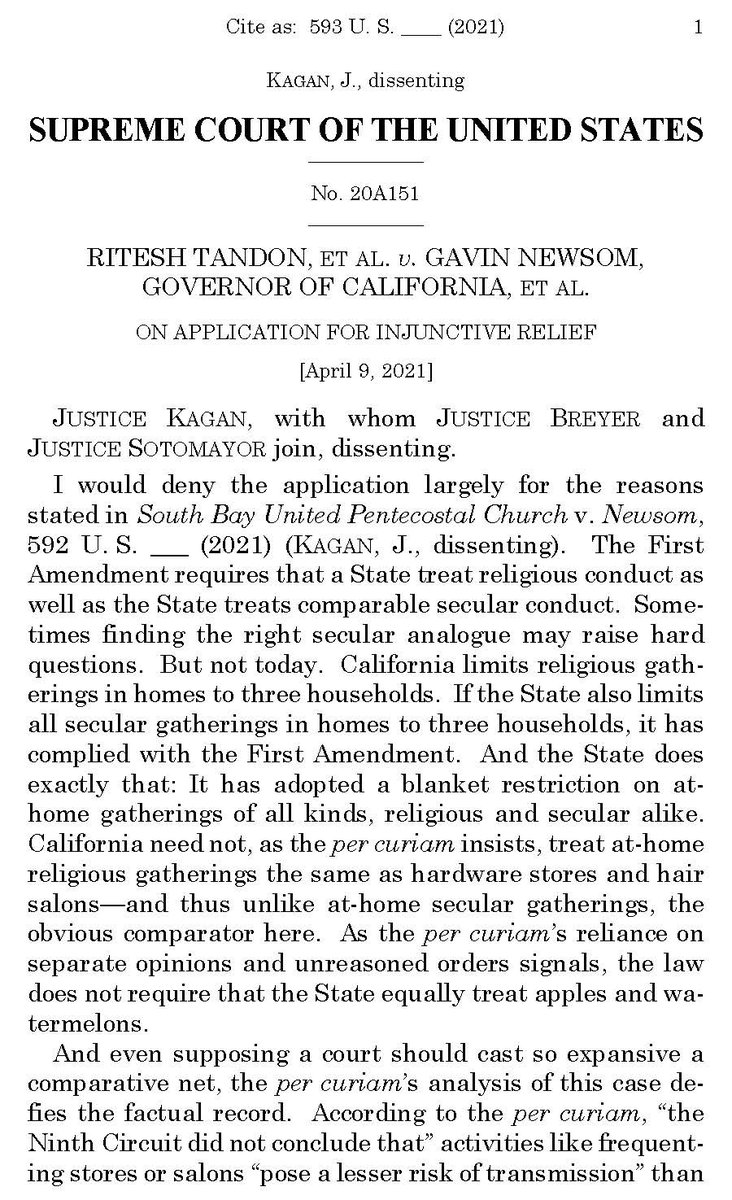

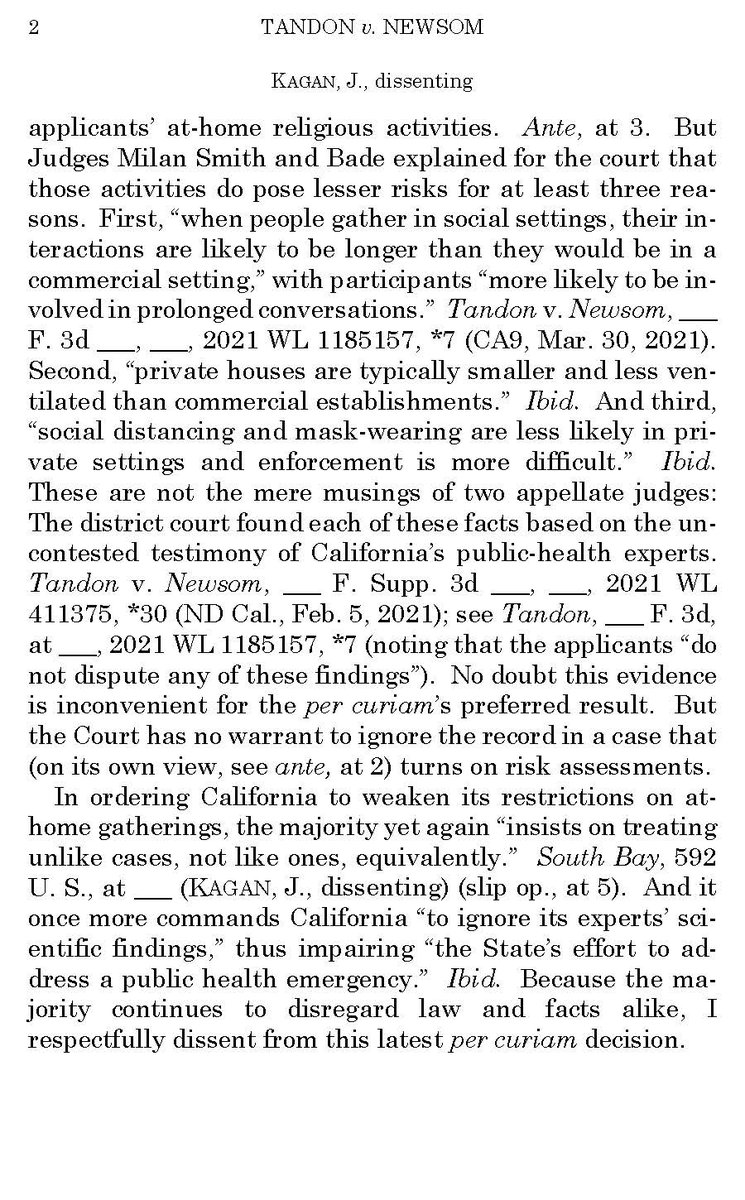

13 of these rulings have provoked at least three Justices to publicly dissent; and last night's is the third to provoke (the same four) Justices to dissent—the Chief Justice and Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan (the latter three of whom joined in a short dissenting opinion):

This volume is staggering in two respects. First, there have been more of these rulings to this point in the Term (19) than there have been signed rulings in argued cases (18). That is, the status-quo-altering part of the "shadow docket" has—for now—*overtaken* the merits docket.

Second, until recently, the Court was averaging single-digit totals of such rulings each Term, including Terms where there might have been only a handful of status-quo-altering emergency rulings.

We're just *halfway* through the current Term (ends 10/4/21), so 19 is ... a lot.

We're just *halfway* through the current Term (ends 10/4/21), so 19 is ... a lot.

By themselves, the total says nothing about *why* there are now so many more of these rulings—or whether the uptick is more a reflection on the underlying disputes, the lower courts' rulings, or the Justices' views.

I've addressed some of that elsewhere:

harvardlawreview.org/wp-content/upl…

I've addressed some of that elsewhere:

harvardlawreview.org/wp-content/upl…

For now, let me just underscore what the data clearly show: The shadow docket has become not just an *important* feature of #SCOTUS's work, but an increasingly *dominant* one. Whether or not you like the *results* in these cases, that has serious institutional implications.

/end

/end

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh