“To do the right thing under the extreme pressure of combat requires certain personal characteristics and leadership, but it also requires professional knowledge and decision-making skills – and the resulting professional self-confidence.”

During the Interwar Years, there was really only one place that offered the professional education and training necessary to be a proficient @USArmy officer – @FortLeavenworth – positioned “on the bluffs overlooking the Missouri River in Kansas.”

“The only school in the Interwar Army that taught the necessary principles, procedures, and techniques for… combined arms warfare (combined infantry-artillery-tanks-airpower controlled by a staff & led by a commander separated from the immediate tactical decisions)" was @USACGSC

Before WWII began, only the most senior officers were offered the opportunity to attend the Command and General Staff Course, now the Command and General Staff College @USACGSC, and these officers would be “the foundation of effective command and staff functioning” in WWII.

During the Interwar Years, the professional careers of Army officers were not spent exclusively leading troops. Many became students or served as instructors.

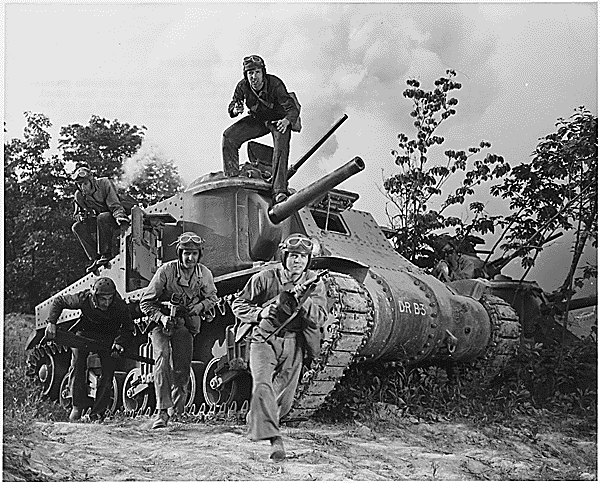

We’ve discussed how underfunded the Army was during the Interwar Years and how this had a significant impact on modernization and overall readiness.

We’ve also discussed efforts to prepare the nation for mobilization – using educational orders to help prime our industrial base to shift to wartime production, as well as efforts to plan the massive expansion of the armed forces.

But something that was crucial to ensuring these processes unfolded in ways that would produce the desired outcome – a massive, modern, combat-ready force trained to fight and win – was the “military competence to bring power effectively to bear” on enemy forces.

Major Frederick Pond, with the Pennsylvania Army National Guard, wrote an article for the January 1930 edition of Infantry Journal, in which he noted the following:

“The World War has made of the Army a great school. We are all of us instructors. We receive instruction in subject matter and take courses in methods of instruction that we may pass our knowledge on to others most efficiently.”

“Indeed, is it not a fair premise to say that in time of peace, the major part of the world of the armed forces is instruction?”

“To this end the appropriations are made, to this end all the organization is accomplished and administered – that men may be instructed to battle proficiency.”

Shortly after WWI ended, then-Colonel George C. Marshall wrote “We found the [division] contained organizations previously unheard of, which were to be armed with implements entirely new to us.”

“Considering that we were starting on an expedition with an objective 3000 miles across the sea, it seemed rather remarkable that we should have embarked without knowledge of the character of the organization we were to fight.”

Marshall met his fellow staff officers the same day they all arrived in New York to board a ship for France.

Marshall would refer to his tasks as some of “the most strenuous, hectic, and laborious” in his experience, realizing that there was a need for all new competencies across all echelons of the army. And even more unique needs when he joined the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

“Marshall, among many others, was experiencing one of the essential characteristics of twentieth-century warfare: the work required of a general staff.”

As Dr. Schifferle notes in American’s School for War, the use of graduates from Fort Leavenworth could help offset the need for training some general staff officers but this would not meet the needs entirely since there was only a small pool of @USACGSC graduates to draw from.

Specifically, there were a little more than 700 since the Spanish-American War and this would not be enough for the more than 3-million soldiers we would have in the field.

General Pershing, who had not attended the schools, created the first general staff system in US history within the AEF. But there were problems.

For example, there was a perception among officers who had not gone to CGSC that the CGSC graduates were “exerting an undue influence on activities, promotions, and military execution.”

“The domination of the AEF staff by Leavenworth graduates cannot be exaggerated. Of 12 staff officers who served as AEF chief of staff, deputy chief of staff, G3, G4, or G5, 9 were Leavenworth graduates.”

They also seemed to dominate general staff positions in field units. “The chiefs of staff of both field armies and the chiefs of staff of 9 of 10 of the corps were [Leavenworth] graduates, as were the chiefs of staff of 23 of the 26 divisions engaged in combat.”

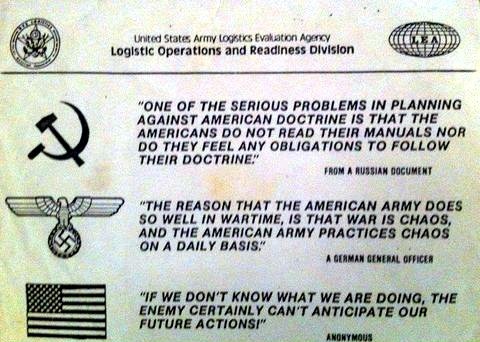

But these CGSC graduates provided something that we now highly value but at the time was a fairly new consideration – “the graduates of Leavenworth provided… a shared language and attitude toward problem solving.”

Charles Herron, CGSC class of 1908 and chief of staff of the 78th Division, when talking of another CGSC grad: “He understood what you said and you understood what he said.”

“None of the army or corps commanders had attended [CGSC], and of the 57 officers who commanded the 26 divisions committed to combat, only 7 were graduates.”

“If there was distrust of the Leavenworth clique, it came not from peers and junior officers, but rather from some of the most senior commanders of the AEF, reflecting a distrust of their educated subordinate staff officers.”

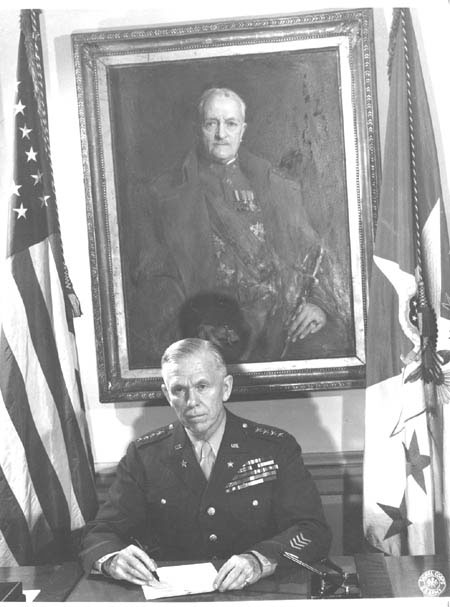

Pershing appeared to be a bit different. Marshall (left), recalling of Pershing (right) after WWI, noted that he “crystalized the appreciation of higher education in the Army, particularly Leavenworth…”

“… upon whose graduates he leaned heavily in France, to such an extent that a standing order required that every Leavenworth graduate disembarking in France would be detached from his unit and sent directly to Chaumont.”

There was a need to train these staff officers and a solution was devised – they would set up a staff school in France, modeled after the Command and General Staff Course at Leavenworth (before 1917).

With some “minor modifications to better align the AEF staff with the French and British staff systems.”

Pershing told the War Department in the fall of 1917 that he wanted 100 officers from the US to be sent for the first class in France.

The War Department replied a few weeks later that they could only find 14 officers available 👀.

Pershing would pull others from units already in France.

Pershing would pull others from units already in France.

The first class started on 28 November 1917 with 75 officers and three months later 42 of them graduated.

This school in France during WWI was obviously different from the Command and General Staff Course at Fort Leavenworth. The AEF course would last only 3 months and there was a focus for officers on skills needed in the positions they would assume once they graduated.

Officers who would go to G3 positions would receive instruction in operations and associated G3 duties, plus brief instruction in general staff procedures.

If you're just tuning in or you've missed any of the previous threads, you can find them all saved on this account under ⚡️Moments or with this direct link twitter.com/i/events/13642…

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh