There is some truth to criticism of Smil's pessimism around energy transitions. The past is an important guide, but at the same time we have not previously had exogenous pressures like climate to force transitions. Where I disagree with @mbarnardca's take is on Gate's investments

https://twitter.com/azeem/status/1393158389908262913

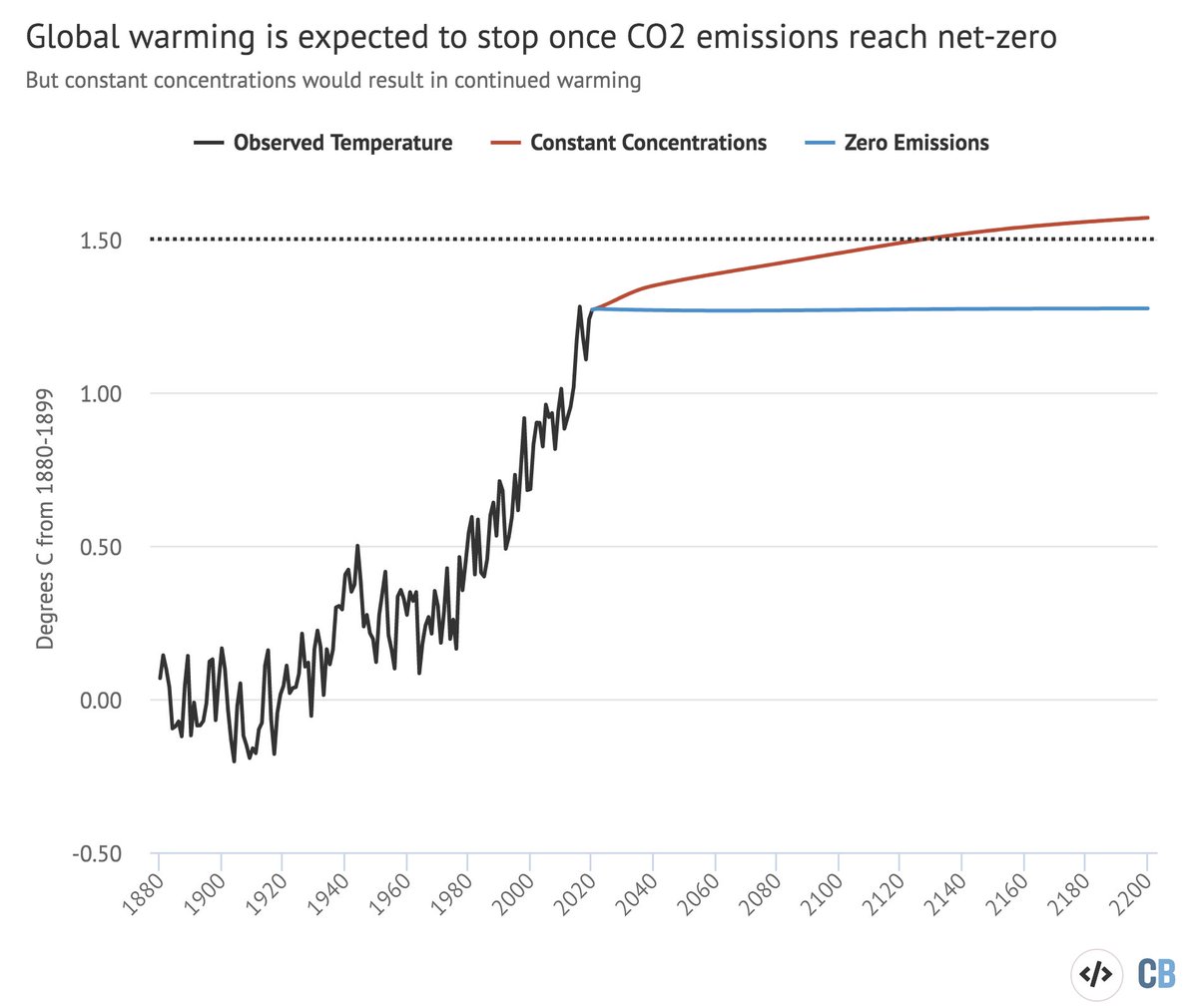

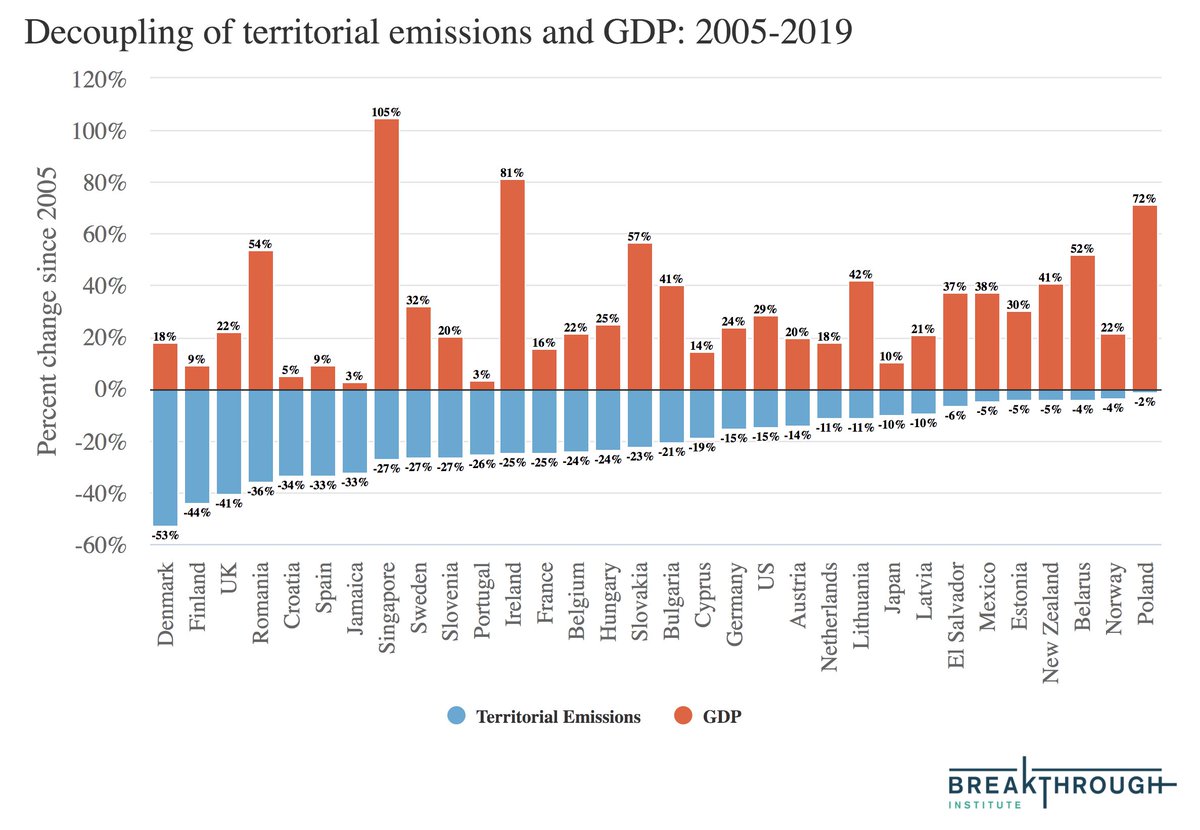

Solar and wind are huge success stories today, and will be the largest drivers of decarbonization for the next few decades. But theres a growing view among energy models that 100% WWS systems – as Jacobson proposes – are much more costly than mixed ones. thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/…

We should be ecumenical about future energy tech, and on any particular technology to fill in the remaining gaps. For that reason I think its great if billionaires throw lots of money at speculative technologies that might not pan out, vs say improving solar efficiency by 2%.

Theres no lack of private sector investment in mature clean energy tech today. Portraying investments in more nascent ones as somehow zero sum is inaccurate. And while most new tech will fail, some might succeed, becoming part of the mix to make decarbonization easier and cheaper

There are also sizable parts of the economy – industrial heat, agriculture, aviation, shipping – where we do not have mature cost-effective clean energy alternatives today, and where more innovation is critically important.

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh