Finished reading this brilliant essay on Tagore’s Perspective on Decolonizing Education. The article discusses 'at length Tagore’s philosophy of education, as well as his concrete efforts to establish an alternative model of a school and a university.

oxfordre.com/education/view…

oxfordre.com/education/view…

Tagore was a polymath who spent most of his adult life building a school and a university, alongside creating an impressive opus of literary and artistic work. However, Tagore was himself unsuccessful within the mainstream school and higher education system of British India.

Tagore's critique of Colonial Education:

Tagore wrote his first critical essay on education, শিক্ষার হেরফের (“Sikshar Herfer”), in 1892, which was later published by Visva Bharati University in English as “Vagaries of Education” (Dasgupta, 2009, pp. 440–441).

Tagore wrote his first critical essay on education, শিক্ষার হেরফের (“Sikshar Herfer”), in 1892, which was later published by Visva Bharati University in English as “Vagaries of Education” (Dasgupta, 2009, pp. 440–441).

In this excellent essay, Tagore highlights some serious problems with the mainstream system of education in India, including education in a foreign language, involving unfamiliar content, and imparted by poorly educated teachers.

According to Tagore, education encouraged rote memorization of rules of grammar and sentence structure more than critical thinking and understanding. Hence, he argued strongly in favor of promoting education for Indian children in their mother tongue.

However, Tagore did not reject the idea of learning foreign languages and other cultures. He was not against modern Western scientific & technological education. He emphasized early education in the mother tongue with familiar content to build a strong foundation for students.

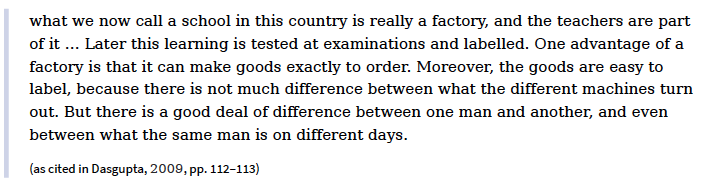

Tagore on Structure of Schools:

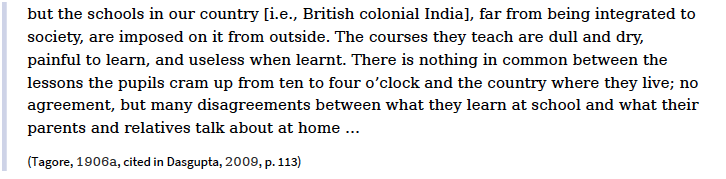

Tagore launched a scathing critique of the entire design and architecture of the school system in colonial India in the essay শিক্ষ্যা সমস্যা (“Shiksa Shamasya”), meaning “The Problem of Education,” in 1906.

Tagore launched a scathing critique of the entire design and architecture of the school system in colonial India in the essay শিক্ষ্যা সমস্যা (“Shiksa Shamasya”), meaning “The Problem of Education,” in 1906.

Tagore further argues that the schooling systems in Europe were an integral part of their society, while in India;

Reflecting on his own experiences as a child, Tagore says “the child’s life is subjected to the education factory, lifeless, colourless, dissociated from the context of the universe, within bare white walls staring like eyeballs of the dead” (cited in Dasgupta, 2009, p. 108).

Tagore on Pedagogy:

This painful pedagogic process of education in the factory model of schools was symbolically critiqued by Tagore in his own artistic way through the medium of a satirical short story, তোতাকাহিনী (“A Parrot’s Training”), in 1918.

This painful pedagogic process of education in the factory model of schools was symbolically critiqued by Tagore in his own artistic way through the medium of a satirical short story, তোতাকাহিনী (“A Parrot’s Training”), in 1918.

The entire satirical children’s story was a parody of the mainstream bookish school system that deprives the child of all the joys of learning and kills all creative possibilities. Tagore’s critique of bookish knowledge can be also found in the essay আবরণ (“Children’s Clothes”);

The harrowing and painful impact of such a “parrot’s training” kind of discipline and punishing pedagogy on the child’s psychology has been also recorded by Tagore (1917a, p.6) in his childhood reminiscences, where he recollects some of his educational experiences:

Tagore on Decolonizing Education:

Tagore strongly believed that the higher and the most important purpose of education was to achieve freedom and joy in learning for creativity and self-fulfillment. Tagore (1919b), in the essay “My School,” writes;

Tagore strongly believed that the higher and the most important purpose of education was to achieve freedom and joy in learning for creativity and self-fulfillment. Tagore (1919b), in the essay “My School,” writes;

According to him, an ideal education system for any society needs to centered around its culture. In his essay “The Centre of Indian Culture,” Tagore writes;

“our education should be in full touch with our complete life, economical, intellectual, aesthetic, social & spiritual."

“our education should be in full touch with our complete life, economical, intellectual, aesthetic, social & spiritual."

In conclusion, it can be said that Tagore’s decolonizing of education was indeed a very courageous, ambitious, and successful project in British India. As Collins (2011b) argues;

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh