#MedicalTwitter, this is not OK.

Please look at this story, & the responses, to see the uphill struggle we have to talk with compassion about CPR to people who are sick, frightened & not accompanied by their loved ones during this time of covid.

Some comments:

1/

Please look at this story, & the responses, to see the uphill struggle we have to talk with compassion about CPR to people who are sick, frightened & not accompanied by their loved ones during this time of covid.

Some comments:

1/

https://twitter.com/AndyWoodturner/status/1401208658764120070

Firstly, I have been the doctor whose words were relayed by a v sick patient to a relative, & what the relative heard was not what I said. But it WAS what the patient/family understood from what I said, so I was responsible for that miscommunication.

Communication matters.

2/

Communication matters.

2/

CPR isn't really 'treatment.' It's a bridge to treatment in an emergency. Sometimes it works. But it's not like on TV.

Most people don't know that, so how we explain it really matters.

3/

Most people don't know that, so how we explain it really matters.

3/

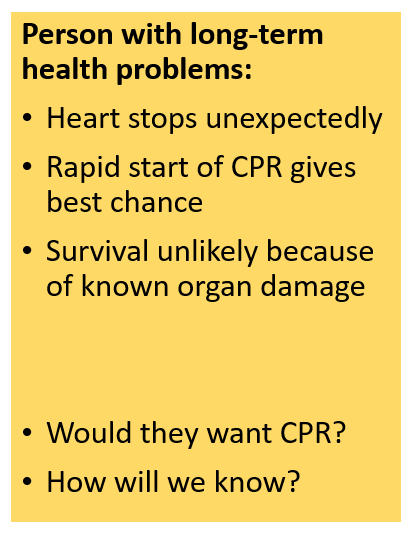

When we are communicating about CPR, there are different possible scenarios. The public isn't always clear about them, so we need to be very clear indeed.

CPR is only ever going to work when the heart stops first, & when the patient's other organs are relatively healthy.

4/

CPR is only ever going to work when the heart stops first, & when the patient's other organs are relatively healthy.

4/

It isn't ageist to talk about lower survival in older people, it's just the truth.

Just like it's the truth that people of any age with severe & already life-limiting illness are unlikely to benefit.

So every patient always requires individual, personalised assessment.

5/

Just like it's the truth that people of any age with severe & already life-limiting illness are unlikely to benefit.

So every patient always requires individual, personalised assessment.

5/

After assessment, we have a duty to protect patients from harm. For some, we escalate medical interventions to protect (if we can) from dying.

For those who cannot survive, our duty is to protect from harmful, unhelpful treatments.

This needs clear, compassionate communication.

6

For those who cannot survive, our duty is to protect from harmful, unhelpful treatments.

This needs clear, compassionate communication.

6

So how do we communicate with clarity & kindness?

By being clear in our own mind first, & walking patient/family through the assessment.

CPR decisions fall into three scenarios.

Here's a summary slide - we'll consider each in turn.

7/

By being clear in our own mind first, & walking patient/family through the assessment.

CPR decisions fall into three scenarios.

Here's a summary slide - we'll consider each in turn.

7/

Scenario 1: person in full health (includes people living with stable physical disability, learning disability, mental health problems) whose heart stops unexpectedly.

Survival chance 10-20% if CPR by trained bystander starts immediately.

8/

Survival chance 10-20% if CPR by trained bystander starts immediately.

8/

Scenario 1: CPR might succeed. The consent question is 'Would you accept CPR if it was medically necessary?' They have a right to refuse: then a DNACPR statement is needed to respect their decision. They may already have an ADRT refusing CPR.

It's their right to say no.

9/

It's their right to say no.

9/

Scenario 2: The person's organs are already struggling, so if the heart stops that would be the final blow: CPR would not be medically possible.

Futile CPR should not be started, & this needs to be communicated with gentle clarity: the patient has a right to know.

10/

Futile CPR should not be started, & this needs to be communicated with gentle clarity: the patient has a right to know.

10/

Scenario 3: the person is dying. Instead of their heart stopping first, it stops last at the end of the gradual process of dying. CPR will not reverse this. It is as inappropriate as surgery.

This is not a 'consent' conversation. Instead...

11/

This is not a 'consent' conversation. Instead...

11/

A DNACPR decision made on the grounds of medical futility requires a tender conversation to explain that death is approaching (months, days, hours) & that we will not mistake death for a cardiac arrest. We will protect from CPR via DNACPR statement.

12/

12/

The doctor in the original tweet did not communicate well. It's not clear whether she was too tired, too inexperienced, too busy, not sufficiently trained: it's unlikely she was simply unkind. Whatever happened, that is a system failure. She should not shoulder all the blame.

13/

13/

In the end, it's all about communication.

Being clear in your mind about the place of CPR.

Being clear about consent to treat: it's never consent NOT to treat.

Being clear by acquiring, practising, reviewing communication skills.

Being clear about what we have communicated...

14/

Being clear in your mind about the place of CPR.

Being clear about consent to treat: it's never consent NOT to treat.

Being clear by acquiring, practising, reviewing communication skills.

Being clear about what we have communicated...

14/

At the end of the conversation, asking the person to tell us how they will explain to their loved ones is a good way to help them prepare for that task and to check there are no misunderstandings.

Patients' misunderstanding of medical info is not their fault, but ours.

15/

Patients' misunderstanding of medical info is not their fault, but ours.

15/

Better public understanding of what CPR is, its limitations, & people's rights to say no but not to demand futile treatments would make these conversations less distressing for our patients.

This could be taught whenever people are taught CPR, including in schools.

16/

This could be taught whenever people are taught CPR, including in schools.

16/

It's time for a national information campaign using TV dramas, media articles, social media campaigns, etc. This should be government led as sought by @katemasters67 & @ShaunLintern.

The public has a right to better information to support such difficult medical discussions.

17/17

The public has a right to better information to support such difficult medical discussions.

17/17

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh