This is starting now! Will be doing some livetweeting.

https://twitter.com/d_stoekl/status/1402892647744815109

After a summary of his original argument, @IdanDershowitz moves on to discussing some major points of criticism.

Against my argument that V contradicts the literary reconstructions Idan cites, he states that it agrees with them for 97%. Not sure whether this is a rhetorical figure or what it is based on otherwise. IMO, the disagreements are important, things like:

- Joshua and Caleb being mentioned in a text that supposedly lacks a spies narrative;

- the ark being mentioned in a passage that is reconstructed without any mention of the ark;

- frequent retention of words and phrases from the missing verses, showing the forger knew them.

- the ark being mentioned in a passage that is reconstructed without any mention of the ark;

- frequent retention of words and phrases from the missing verses, showing the forger knew them.

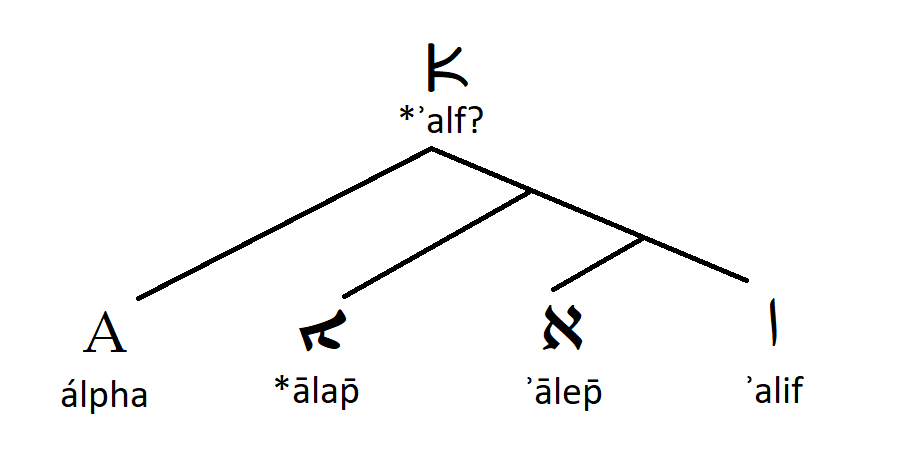

Idan focuses on Ron Hendel's suggestion that the forger was inspired by the Siloam Inscription, but does not address Hendel's main point, that V's orthography contradicts everything we know about the history of Hebrew spelling. I do agree with Idan...

... that the Siloam Inscription did not influence V's spelling (as it had not yet been discovered when the forgery was made).

See Hendel's paper here, and the conclusion in the image, which clearly shows that the argument does not stand or fall with influence from Siloam; Mesha is much more meaningful. academia.edu/49061793/Notes…

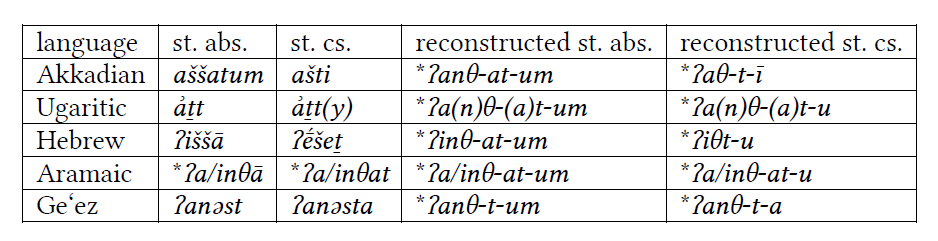

Na'ama Pat-El continues, replying to some linguistic points. First of all, notes that while ʕēḏūṯ 'testimony' is not attested in Biblical Hebrew, it could have occurred in Classical Hebrew; and that the spelling of gentilic plurals without y is unproblematic.

Next points are that 'his' spelled with -w is marginally attested in pre-exilic inscriptions (one or two examples); and that correspondences with 19th-c. Hebrew would only be meaningful if they do not occur in pre-exilic Hebrew. I have tried to show that some of these do not...

... such as negation with לא for here-and-now negative commands, the phrase בעת הזאת 'at this time'. The use of w-qatal for the past tense, much more common in V than in pre-exilic Hebrew (if it occurs there at all), is also normal in the 19th century.

Conclusion: hand-written catalogues reveal Shapira's genuine interest in the manuscripts he sold and efforts to assure their authenticity.

On the paleography of V, Benny Sass argues that if the drawings are not (intended as) facsimiles, they are unreliable by default.

Reiterates the argument about the zigzag yod matching later discoveries.

@MatthRichelle continues the discussion of paleography (full paper here: academia.edu/48905750/The_S…)

Some arguments: Guthe and Ginsberg did not base their transcriptions on the letter forms they already knew from other inscriptions, as they do not match those; Ginsberg's final draft seems quite reliable as far as the graphemes are concerned at least.

A nice illustration of the asynchrony of V's paleography and correspondences with the forged Moabite pottery.

Back after the break with Robert Holmstedt, who presents some new linguistic arguments against V's authenticity (read the paper here: academia.edu/49192757/Shapi…)

Interesting statistic: Dershowitz & Pat-El indirectly refer back to an article that finds only 49 cases of w-qatal as narrative past tense in the whole Hebrew Bible. None occur in Deuteronomy.

"I think what you have [in V] is the slipping in of a later stage of Hebrew"—agreed🙂

"I think what you have [in V] is the slipping in of a later stage of Hebrew"—agreed🙂

The convener, @d_stoekl, will consider a codicological point: the folds in the manuscripts.

Konrad Schmid: there are multiple hypothesis, not one yes-no question. He will focus on the strongest claim, that V is a proto-biblical book.

Schmid takes the Decalogue as a case study and presents five arguments why V's Decalogue is dependent on MT, not vice versa. 1: V is more unambiguously a DECAlogue (clarification of how to count the Ten Commandments through repetition of the refrain אנך אלהם אלהך).

It is much easier to understand how the MT Decalogues and other material was turned into V's version than the other way around.

V also merges the commandments against false oaths and false testimonies and seems to show more modern theological opinions. Ironically, I have lost count of the Five Arguments because I was getting Idan's book from the bookcase to read along.

This is a very nice argument because it's conceptually quite similar to a lot of what @IdanDershowitz argues. Schmid cites recent literature arguing that the use of אלהים as such as a divine name is late and originates with the Priestly source, which V is supposedly free of.

Based on the earlier perspective of Deuteronomy's Decalogue from the point of view of history of Israelite religion as the Fifth Argument, Schmid concludes that V does not have priority over Deuteronomy.

To clear that up: this was the fifth main argument, and that was the conclusion, which was based on all the arguments.

Last speaker, Jeffrey Stackert, continues the literary analysis. Stackert cites the Pentateuchal J source as a possibly parallel for a narrative source without a law code attached and cites other similarities between V and J.

One of these similarities, however, suggests V's dependence on a combined Pentateuch text as known to us, if God's performing miracles 'these ten times' refers to the Ten Plagues in Egypt.

V contains material building on—and "improving upon"—a passage in Deuteronomy that Stackert argues is post-Priestly.

Stackert concludes by saying that the more he looks into it, the more skeptical he becomes of V's authenticity. This seems to sum up the general mood well.

The Q&A session will start after a break, but I'll miss most of it, so here endeth the livetweet. Thanks for reading!

The Q&A session will start after a break, but I'll miss most of it, so here endeth the livetweet. Thanks for reading!

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh