It’s almost impossible to predict the future. But it’s also unnecessary, because *most people are living in the past*.

All you have to do is see the present before everyone else does.

All you have to do is see the present before everyone else does.

Less pithy, but more clear:

Most people are slow to notice and accept change. If you can just be faster than most people at seeing what’s going on, updating your model of the world, and reacting accordingly, it's almost as good as seeing the future.

Most people are slow to notice and accept change. If you can just be faster than most people at seeing what’s going on, updating your model of the world, and reacting accordingly, it's almost as good as seeing the future.

We see this in the US with covid. The same people who didn’t realize that we all should be wearing masks, when they were life-saving, are now slow to realize/admit that we can stop wearing them.

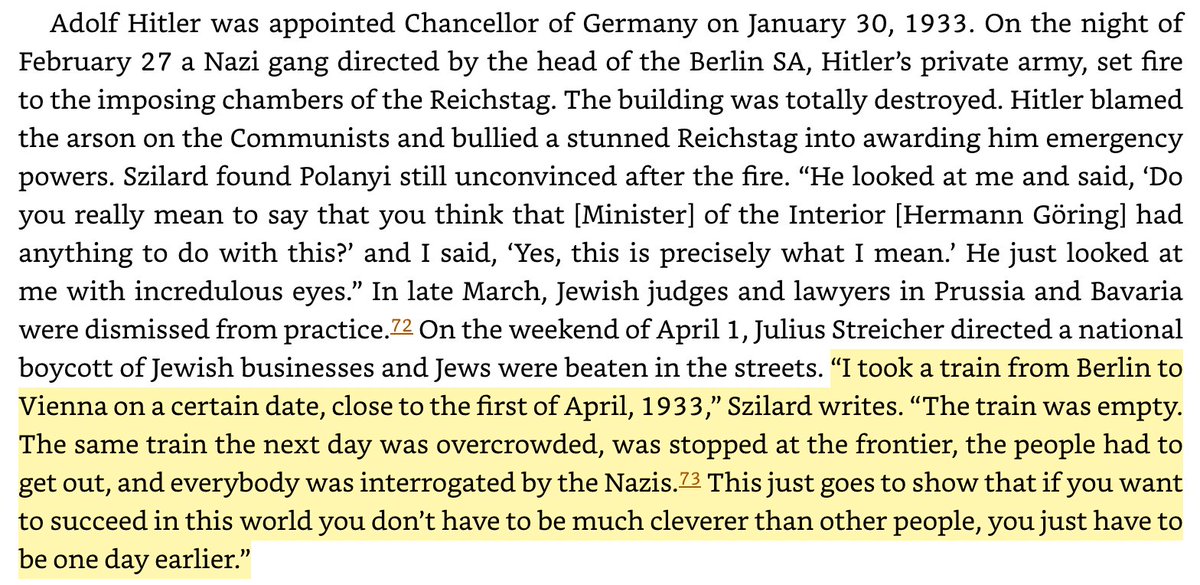

For a dramatic historical example (from *The Making of the Atomic Bomb*), take Leo Szilard’s observations of 1930s Germany: “you just have to be one day earlier”

How to be earlier?

1. Independent thinking. If you only believe things that are accepted by the majority of people, then by definition you’ll always be behind the curve in a changing world.

1. Independent thinking. If you only believe things that are accepted by the majority of people, then by definition you’ll always be behind the curve in a changing world.

2. Listen to other independent thinkers.

You can’t pay attention to everything at once or evaluate every area. You can only be the *first* to realize something in a narrow domain in which you are an expert.…

You can’t pay attention to everything at once or evaluate every area. You can only be the *first* to realize something in a narrow domain in which you are an expert.…

But if you tune your intellectual radar to other independent thinkers, you can be in the first ~1% of people to realize a new fact. Seek them out, find them, and follow them.

I was taking covid precautions in late February 2020, about three weeks ahead of official “lockdown” measures—but only because I was tuned in to the people who were *six* weeks ahead.

But:

3. Distinguish independent thinkers from crackpots. Both are “contrarian”; only one is right.

This is an art, honed over decades. Pay attention to both the source's evidence and their logic. Credentials are relevant, but they are neither necessary nor sufficient.

3. Distinguish independent thinkers from crackpots. Both are “contrarian”; only one is right.

This is an art, honed over decades. Pay attention to both the source's evidence and their logic. Credentials are relevant, but they are neither necessary nor sufficient.

4. Read broadly; seek out and adopt concepts and frameworks that help you understand the world (e.g.: exponential growth, network effects, efficient frontiers).

Finally:

5. Learn how to make decisions in the face of uncertainty.

Even when you see the present earlier, you won’t see it with full clarity, nor will you be able to predict the future. You’ll just have a set of probabilities that are closer to reality than most people’s.

5. Learn how to make decisions in the face of uncertainty.

Even when you see the present earlier, you won’t see it with full clarity, nor will you be able to predict the future. You’ll just have a set of probabilities that are closer to reality than most people’s.

To return to the covid example: in January/February 2020, even the people farthest ahead of the curve weren’t certain whether there would be a pandemic or how bad it would be. They just knew that the chances were double-digit percent, before it was even on most people’s radar.

Find low-cost ways to avoid extreme downside, and low-investment opportunities for extreme upside. For example, when a pandemic *might* be starting, it makes sense to stock up on supplies, move meetings to phone calls, etc.—these are cheap insurance.

In some fantasy worlds, there are superheroes with “pre-cognition”, able to see the immediate future. They’re always one step ahead. But since most people are a few steps *behind* reality, you don’t need pre-cognition—just independent thinking.

This thread as a blog post: jasoncrawford.org/precognition

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh