1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll walk you through the key differences between *earnings* and *cash flows*.

The punch line: Just because a company reports $1 of *earnings*, it does NOT mean the company has $1 more *cash* to distribute to owners.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I'll walk you through the key differences between *earnings* and *cash flows*.

The punch line: Just because a company reports $1 of *earnings*, it does NOT mean the company has $1 more *cash* to distribute to owners.

2/

Before we look at a company's *earnings*, it's useful to understand the concept of Net Worth.

Net Worth (also called Book Value, or Shareholder's Equity) is simply the difference between what a company *owns* (ie, its assets) and what it *owes* (ie, its liabilities).

Before we look at a company's *earnings*, it's useful to understand the concept of Net Worth.

Net Worth (also called Book Value, or Shareholder's Equity) is simply the difference between what a company *owns* (ie, its assets) and what it *owes* (ie, its liabilities).

3/

Companies typically *own* a bunch of assets.

These include cash, "accounts receivable" (ie, money owed to the company by customers), "inventory" (ie, raw materials and finished products), "property, plant, and equipment" (ie, land, buildings, and factories), etc.

Companies typically *own* a bunch of assets.

These include cash, "accounts receivable" (ie, money owed to the company by customers), "inventory" (ie, raw materials and finished products), "property, plant, and equipment" (ie, land, buildings, and factories), etc.

4/

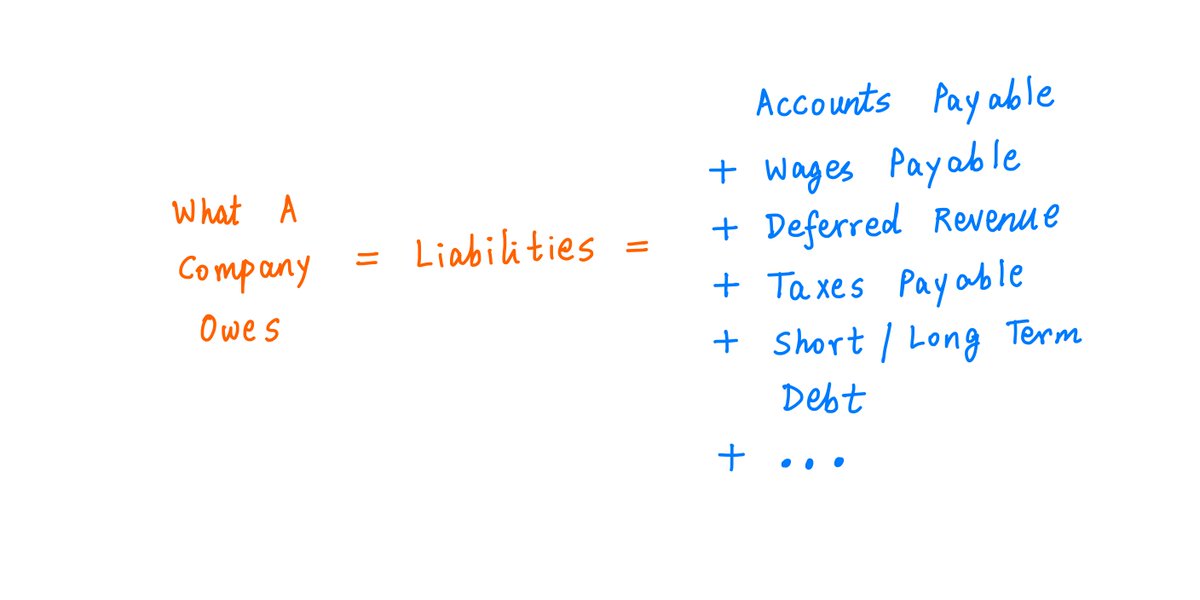

Also, companies typically *owe* money or services to others (liabilities).

These include "accounts payable" (money owed to suppliers), "wages payable" (ie, money owed to employees for work they've already done), debt taken out by the company that has to be repaid, etc.

Also, companies typically *owe* money or services to others (liabilities).

These include "accounts payable" (money owed to suppliers), "wages payable" (ie, money owed to employees for work they've already done), debt taken out by the company that has to be repaid, etc.

5/

Net Worth is what remains after we net out what a company *owns* against what it *owes*.

Companies that *own* more than they *owe* have positive net worth.

Companies that *owe* more than they *own* have negative net worth.

Net Worth is what remains after we net out what a company *owns* against what it *owes*.

Companies that *own* more than they *owe* have positive net worth.

Companies that *owe* more than they *own* have negative net worth.

6/

When a company reports $1 in *earnings*, it means the company's Net Worth has increased by $1 -- assuming the company hasn't yet distributed any part of that $1 to its owners.

Thus, Earnings = Increase in Net Worth.

Here's a quick picture:

When a company reports $1 in *earnings*, it means the company's Net Worth has increased by $1 -- assuming the company hasn't yet distributed any part of that $1 to its owners.

Thus, Earnings = Increase in Net Worth.

Here's a quick picture:

7/

The crucial thing to understand is:

Increase in Net Worth does not mean Increase in Cash.

For example, a $1 increase in net worth can be achieved by a $0.50 increase in accounts receivable and a $0.50 *decrease* in accounts payable -- without touching cash on hand.

The crucial thing to understand is:

Increase in Net Worth does not mean Increase in Cash.

For example, a $1 increase in net worth can be achieved by a $0.50 increase in accounts receivable and a $0.50 *decrease* in accounts payable -- without touching cash on hand.

8/

But then, as long-term investors, when we shell out cash to buy a company, what we're hoping for is that the company will eventually return more *cash* to us (in the form of dividends) than what we paid for it.

But then, as long-term investors, when we shell out cash to buy a company, what we're hoping for is that the company will eventually return more *cash* to us (in the form of dividends) than what we paid for it.

9/

We expect this cash to come from the company's earnings over time.

But if these earnings are NOT in the form of cash (ie, if they just show up as an increase in *non-cash* assets like receivables), then the company can't very well return *cash* to us on a sustained basis.

We expect this cash to come from the company's earnings over time.

But if these earnings are NOT in the form of cash (ie, if they just show up as an increase in *non-cash* assets like receivables), then the company can't very well return *cash* to us on a sustained basis.

10/

In a nutshell, that's the problem with *earnings*.

Earnings tell us nothing about how much *cash* can actually be returned to owners.

To understand the latter, we need to look at the company's *cash flows* in addition to its earnings.

In a nutshell, that's the problem with *earnings*.

Earnings tell us nothing about how much *cash* can actually be returned to owners.

To understand the latter, we need to look at the company's *cash flows* in addition to its earnings.

11/

A company's Income Statement usually presents its earnings (ie, Net Income) as Revenues minus Costs:

Earnings = Revenues - Costs.

But both Revenues and Costs contain *non-cash* components.

These account for much of the difference between *earnings* and *cash flows*.

A company's Income Statement usually presents its earnings (ie, Net Income) as Revenues minus Costs:

Earnings = Revenues - Costs.

But both Revenues and Costs contain *non-cash* components.

These account for much of the difference between *earnings* and *cash flows*.

12/

For example, suppose a company delivers its products to customers, but doesn't get paid right away.

That's *non-cash* revenue. It contributes to earnings, but not to cash. It shows up on the balance sheet as an increase in accounts receivable, a non-cash asset.

For example, suppose a company delivers its products to customers, but doesn't get paid right away.

That's *non-cash* revenue. It contributes to earnings, but not to cash. It shows up on the balance sheet as an increase in accounts receivable, a non-cash asset.

13/

On the other hand, suppose a company takes delivery of raw materials from suppliers, but doesn't pay them right away.

That's a non-cash *cost*. It detracts from earnings, but not from cash. It shows up on the balance sheet as an increase in accounts payable.

On the other hand, suppose a company takes delivery of raw materials from suppliers, but doesn't pay them right away.

That's a non-cash *cost*. It detracts from earnings, but not from cash. It shows up on the balance sheet as an increase in accounts payable.

14/

This is the fundamental difference between "Cash Accounting" and "Accrual Accounting".

Cash Accounting means revenues are recognized when cash is received. Even if the cash is for goods that were delivered during an earlier reporting period.

This is the fundamental difference between "Cash Accounting" and "Accrual Accounting".

Cash Accounting means revenues are recognized when cash is received. Even if the cash is for goods that were delivered during an earlier reporting period.

15/

By the same token, costs are recognized when cash goes out the door.

Even if the cash is used to build a factory that will produce revenues in several *future* reporting periods.

By the same token, costs are recognized when cash goes out the door.

Even if the cash is used to build a factory that will produce revenues in several *future* reporting periods.

16/

But GAAP Income Statements don't use Cash Accounting.

They use *Accrual* Accounting, which tries to match up each Revenue and Cost to its "most appropriate" reporting period.

Even if *cash* for these revenues/costs is received/paid during some other period.

But GAAP Income Statements don't use Cash Accounting.

They use *Accrual* Accounting, which tries to match up each Revenue and Cost to its "most appropriate" reporting period.

Even if *cash* for these revenues/costs is received/paid during some other period.

17/

Accrual Accounting is a major reason why *earnings* don't equal *increase in cash*.

To help us reconcile the two, companies report Cash Flow Statements.

These statements tell us how much of *earnings* actually showed up as an increase in *cash*, and where the rest went.

Accrual Accounting is a major reason why *earnings* don't equal *increase in cash*.

To help us reconcile the two, companies report Cash Flow Statements.

These statements tell us how much of *earnings* actually showed up as an increase in *cash*, and where the rest went.

18/

For example, *depreciation* is a non-cash cost.

It's the cost of the assets that were "used up" to produce revenue during the *current* reporting period.

But the *cash* used to buy those assets went out the door a long time ago -- during some *previous* reporting period.

For example, *depreciation* is a non-cash cost.

It's the cost of the assets that were "used up" to produce revenue during the *current* reporting period.

But the *cash* used to buy those assets went out the door a long time ago -- during some *previous* reporting period.

19/

So, what does the Cash Flow Statement do?

It takes all costs like depreciation -- which reduced earnings but did NOT reduce cash during the current period.

Then it adds these "non-cash" costs back to earnings, to reconcile earnings with cash.

So, what does the Cash Flow Statement do?

It takes all costs like depreciation -- which reduced earnings but did NOT reduce cash during the current period.

Then it adds these "non-cash" costs back to earnings, to reconcile earnings with cash.

20/

Stock Based Compensation (SBC) is another "non-cash" cost. It's also added back to earnings.

SBC is a special kind of cost. Unlike depreciation, it's not "pre-paid".

It also doesn't decrease the company's net worth.

But it dilutes each *owner's* stake in the company.

Stock Based Compensation (SBC) is another "non-cash" cost. It's also added back to earnings.

SBC is a special kind of cost. Unlike depreciation, it's not "pre-paid".

It also doesn't decrease the company's net worth.

But it dilutes each *owner's* stake in the company.

21/

Non-cash items may show up on the Revenues side as well.

For example, if the company sells products on credit, such sales boost Revenues (and hence earnings), but not cash.

Accordingly, the Cash Flow Statement *subtracts* such non-cash revenues from earnings.

Non-cash items may show up on the Revenues side as well.

For example, if the company sells products on credit, such sales boost Revenues (and hence earnings), but not cash.

Accordingly, the Cash Flow Statement *subtracts* such non-cash revenues from earnings.

22/

Credit sales show up as an increase in accounts receivable -- a "working capital" asset.

Inventory is another such asset.

Every $1 increase in such working capital assets comes from earnings "at the expense of" a $1 increase in cash.

Credit sales show up as an increase in accounts receivable -- a "working capital" asset.

Inventory is another such asset.

Every $1 increase in such working capital assets comes from earnings "at the expense of" a $1 increase in cash.

23/

So, the Cash Flow Statement *subtracts* all such "working capital asset increases" from earnings.

By the same logic, all increases in working capital *liabilities* are *added* to earnings.

Such liabilities include accounts payable, wages payable, deferred revenues, etc.

So, the Cash Flow Statement *subtracts* all such "working capital asset increases" from earnings.

By the same logic, all increases in working capital *liabilities* are *added* to earnings.

Such liabilities include accounts payable, wages payable, deferred revenues, etc.

24/

If we take all these adjustments together, we end up with the company's operating cash flows, or Cash Flow from Operations (CFO):

If we take all these adjustments together, we end up with the company's operating cash flows, or Cash Flow from Operations (CFO):

25/

The other side of the "depreciation" coin is "capital expenses" (or capex).

If depreciation is a cost deducted now for which the cash was "pre-paid" a long time ago, capex is cash that the company is pre-paying *now*, to be deducted as a cost in future.

The other side of the "depreciation" coin is "capital expenses" (or capex).

If depreciation is a cost deducted now for which the cash was "pre-paid" a long time ago, capex is cash that the company is pre-paying *now*, to be deducted as a cost in future.

26/

In other words, capex is cash the company is investing in its operations today, which it will expense over time.

That means: for every $1 of capex the company spends today, there's $1 less cash available to distribute to owners today.

In other words, capex is cash the company is investing in its operations today, which it will expense over time.

That means: for every $1 of capex the company spends today, there's $1 less cash available to distribute to owners today.

27/

That's why Buffett likes to make a distinction between "maintenance capex" and "growth capex".

Maintenance is when a company has to spend cash today simply to *preserve* its current earning power.

In other words, if this cash is *not* spent, earnings will be hurt.

That's why Buffett likes to make a distinction between "maintenance capex" and "growth capex".

Maintenance is when a company has to spend cash today simply to *preserve* its current earning power.

In other words, if this cash is *not* spent, earnings will be hurt.

28/

So, maintenance capex is a kind of "compulsory" re-investment.

The company has no choice. It *cannot* distribute this cash to owners without hurting itself.

So, maintenance capex is a kind of "compulsory" re-investment.

The company has no choice. It *cannot* distribute this cash to owners without hurting itself.

29/

Growth capex, on the other hand, is cash that's spent to *increase* earnings.

There's no gun to the company's head. If this cash is distributed to owners, there will be no adverse impact on future earnings. They may not grow, but they won't shrink either.

Growth capex, on the other hand, is cash that's spent to *increase* earnings.

There's no gun to the company's head. If this cash is distributed to owners, there will be no adverse impact on future earnings. They may not grow, but they won't shrink either.

30/

So, the company's management gets to choose whether to re-invest this money or return it to owners.

For example, management may decide to re-invest only when they feel there's a high likelihood of earning very attractive returns on such re-invested capital.

So, the company's management gets to choose whether to re-invest this money or return it to owners.

For example, management may decide to re-invest only when they feel there's a high likelihood of earning very attractive returns on such re-invested capital.

31/

This is partly why Buffett decided to pivot away from Berkshire Hathaway's original textile business.

Textiles were "high maintenance capex". They forced Buffett to re-invest large sums of capital year after year; if he didn't, earnings would decline.

This is partly why Buffett decided to pivot away from Berkshire Hathaway's original textile business.

Textiles were "high maintenance capex". They forced Buffett to re-invest large sums of capital year after year; if he didn't, earnings would decline.

32/

Whereas a business like See's Candies was the opposite.

The business didn't require much maintenance capex at all.

It generated a lot of cash for Buffett each year, nearly all of which he was free to extract and re-invest elsewhere. And earnings would still not decline.

Whereas a business like See's Candies was the opposite.

The business didn't require much maintenance capex at all.

It generated a lot of cash for Buffett each year, nearly all of which he was free to extract and re-invest elsewhere. And earnings would still not decline.

33/

From a cash flow perspective, cash used for acquisitions is similar to capex.

This is also cash spent today, with the hope of increasing earnings in the future.

And every $1 used to acquire another business is $1 that cannot be distributed to owners today.

From a cash flow perspective, cash used for acquisitions is similar to capex.

This is also cash spent today, with the hope of increasing earnings in the future.

And every $1 used to acquire another business is $1 that cannot be distributed to owners today.

34/

If we subtract both capex and cash acquisitions from CFO, we arrive at Free Cash Flow (FCF).

In many ways, FCF is the metric we were looking for all this while.

It's the cash the company is "free to use" -- to pay down debt, return to owners via dividends or buybacks, etc.

If we subtract both capex and cash acquisitions from CFO, we arrive at Free Cash Flow (FCF).

In many ways, FCF is the metric we were looking for all this while.

It's the cash the company is "free to use" -- to pay down debt, return to owners via dividends or buybacks, etc.

35/

FCF is a useful way to measure how much cash can be returned to owners each year.

But it may not be a *perfect* measure in all cases.

For example, as a precaution, management may opt to keep part of FCF in the company instead of returning it all to owners each year.

FCF is a useful way to measure how much cash can be returned to owners each year.

But it may not be a *perfect* measure in all cases.

For example, as a precaution, management may opt to keep part of FCF in the company instead of returning it all to owners each year.

36/

If there's one thing to take away from this thread, it's this:

Earnings are an opinion. Cash is a fact.

Great companies return a lot of cash to owners over time. Typically, they convert most of their earnings into CFO and FCF, while requiring minimal maintenance capex.

If there's one thing to take away from this thread, it's this:

Earnings are an opinion. Cash is a fact.

Great companies return a lot of cash to owners over time. Typically, they convert most of their earnings into CFO and FCF, while requiring minimal maintenance capex.

37/

If you're still with me, thank you very much!

Please stay safe.

And enjoy the fireworks on this lovely Fourth of July weekend!

/End

If you're still with me, thank you very much!

Please stay safe.

And enjoy the fireworks on this lovely Fourth of July weekend!

/End

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh